Trump’s New National Security Strategy: Is America Really Pulling Out of the Middle East?

The 33-page document centers on redirecting military and political focus toward the Western Hemisphere.

Despite the Trump administration’s direct complicity in the Arab world and the wider Middle East—from the Israeli genocide on Gaza to the aggression on Iran—the president’s new national security strategy sketches a shift in Washington’s priorities, signaling a pullback from the region.

The 33-page document lays out a plan to redirect America’s military and political weight toward the Western Hemisphere and to shore up U.S. economic dominance, a framework the White House is casting as a “new Monroe Doctrine.”

The strategy is anchored in the MAGA vision of “America First,” redefining what Washington sees as its key threats and strategic priorities.

But foreign analysts are skeptical about how much of this pivot can actually be realized, especially as Washington continues to underwrite “Israel” and its war on Gaza, Syria and Lebanon.

They note that Trump, like four presidents before him, has repeatedly promised to scale back involvement in the Middle East, only for policy on the ground to look more like continuity than change.

Shifting the Center of Gravity

Every U.S. administration issues at least one national security strategy to explain how it understands America’s interests and its role in the world. On December 5, 2025, the Trump administration released its new version, the first of the second term, outlining the signals Washington wants to send about how it intends to manage global challenges. This was reported by Modern Diplomacy.

What stands out in this document is its blunt claim that the era of treating the Middle East as the center of American gravity has come to an end. The strategy argues that Washington will reduce its attention to the region because the risks have supposedly diminished, even though the Middle East remains a landscape of overlapping and unpredictable conflicts. The Hill noted the same day that the administration sees this shift as structural rather than tactical.

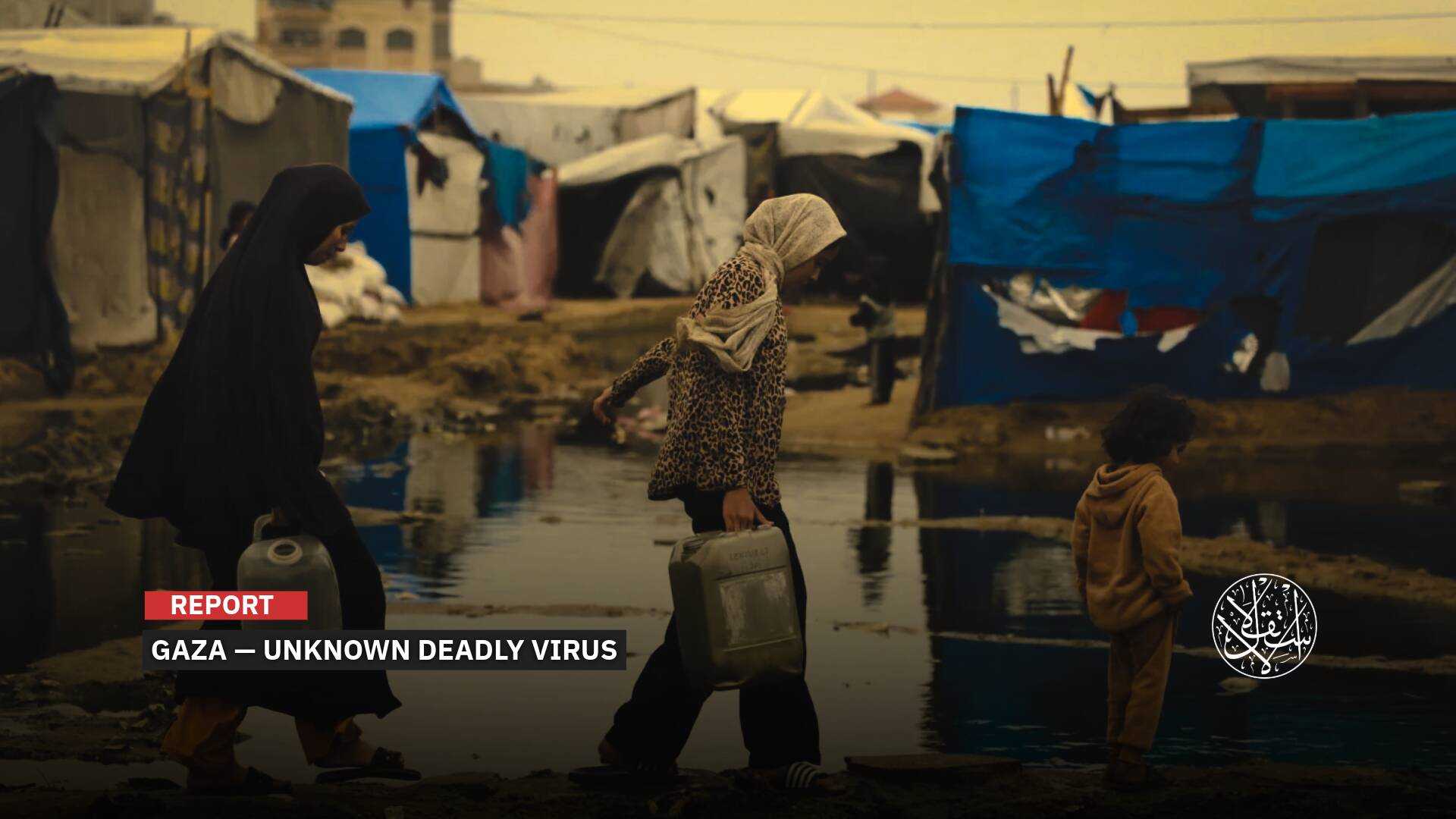

The strategy states that the Middle East no longer dominates American foreign policy in long-term planning or in daily execution because it is no longer seen as a source of constant crises. It reimagines the region as a zone of stability and partnership rather than a generator of global disorder. It credits factors such as Iran’s weakened position, “the ceasefire” in Gaza, the erosion of Hamas’s external backing, and what it describes as new opportunities to stabilize Syria through regional cooperation.

The document also says the United States will not return to large-scale military involvement in the region. Instead, the administration aims to rely on burden sharing with partners and to focus on safeguarding energy supplies, protecting maritime routes, and preventing terrorism.

Skepticism about whether any of this is achievable stems not only from the depth of America’s current involvement in the Middle East. Many analysts say the strategy contradicts the administration’s own behavior.

Although the strategy claims that its foreign policy is not shaped by traditional ideological frameworks, critics argue that the opposite is true. The Intercept reported on November 8, 2025, that the administration’s rhetoric on Nigeria, including threats of airstrikes in the name of protecting Christians, shows how Christian nationalism now influences elements of U.S. foreign policy.

Since returning to office in January 2025, Trump has also been accused of reviving a modern form of hemispheric imperialism. He has spoken openly about reclaiming the Panama Canal and has floated ideas of absorbing Greenland or Canada.

The strategy says that Washington seeks peaceful, trade-based relations with other nations without pressuring them to adopt democratic or social reforms that conflict with their traditions. Yet the administration’s actions tell a different story. Its complicity in wars on Gaza, Lebanon, and Syria, its moves in Latin America, and allegations of interference in elections, all point to a United States that continues to shape global politics through pressure, coercion, and the use of force whenever it believes its interests are at stake.

The strategy’s claim that Washington seeks good relations with countries whose political systems differ from its own has also been met with skepticism. One example is Trump’s insistence, in the strategy’s introduction, that he had brought about peace and reconciliation between Egypt and Ethiopia. The journalist Hafez al-Mirazi questioned the assertion on X, noting that no such breakthrough had occurred.

The administration’s plans for the Middle East, as laid out in the strategy, rest on an unspoken assumption that the region’s conflicts have largely been settled in “Israel’s” favor. In this view, there is no longer a serious threat at play, only what the document calls a complex and contained “dispute” between Israelis and Palestinians.

The strategy also makes two major claims. First, it argues that the Middle East is no longer the world’s most important source of energy because global supplies have diversified and the United States has become a major exporter of oil. Second, it states that the region is no longer a principal arena for great power competition and no longer filled with conflicts that risk spilling across borders. According to the strategy, rivalry between major powers has replaced it as the central global contest.

The document says that conflict in the Middle East has eased because Iran has been weakened by American strikes on its nuclear program and because Trump’s plan has supposedly ended the Israeli wars on Gaza and Lebanon while diminishing Hamas and its supporters.

It concludes that the Arab world is no longer the constant source of looming disaster it once was. The argument relies heavily on the claim that Iran’s influence has receded after the Israeli aggression and the alleged damage inflicted by American attacks on nuclear sites, a narrative that many analysts doubt.

With what it describes as the historical rationale for America’s Middle East focus now fading, particularly the centrality of oil, the strategy imagines the region’s future as a hub for international investment and a platform for nuclear energy, artificial intelligence, and other modern industries.

Democrats have condemned the document as a dangerous withdrawal that could undermine the United States and its allies. Representative Jason Crow warned that the strategy leans on social engineering, cultural warfare and interference in the internal affairs of partner countries. Senator Richard Blumenthal said the strategy throws Ukraine under the bus and turns the slogan “America First” into “America Alone.”

‘Pulling Back Abroad’

The document states plainly that current United States policy is not grounded in traditional political ideologies and that Washington seeks peaceful commercial and diplomatic ties with countries around the world without pushing democratic or social changes that conflict with their own histories and traditions. It also says the United States wants constructive relations with governments whose political systems differ from its own.

Analysts have described this shift as remarkable because it departs from decades of American rhetoric and suggests that the era of democracy promotion and liberal internationalism may be drawing to a close.

According to Modern Diplomacy on December 7, 2025, the Middle East remains important to American interests, but it is no longer central to the country’s broader strategic planning.

Observers believe the Trump administration is unlikely to pull out of the region entirely. Instead, it is expected to reduce its reliance on the Middle East as a pillar of its global role and pivot toward more flexible economic, diplomatic, and commercial partnerships while preserving core interests such as energy supplies and freedom of navigation.

Even so, the outlook for democracy appears increasingly bleak in the strategy. The administration concludes that pushing for democratic reforms is not a priority. It calls the issue a pressing concern but stresses that Washington must not overlook governments whose visions diverge from its own.

The Center for Strategic and International Studies noted in a December 5 report that this stance will be welcomed by regional monarchs. The center argued that the United States seems ready to abandon a long and often misguided effort to pressure Gulf monarchies and others to abandon their traditions and historical forms of governance. The report adds that reform should be encouraged only when it emerges organically and that, under this approach, despots will face no pressure from Washington as long as cooperation remains possible.

Steven Cook, a Middle East and Africa specialist at the Council on Foreign Relations, wrote on December 6 that the strategy’s claim that the region is no longer central to American foreign policy sits uneasily with current reality. He argues that the strategy and the president’s stated preference for a reduced American role are at odds with the actions of the White House since Trump returned to office.

Cook points out that the United States maintains a significant military presence in the Israeli town of “Kiryat Gat,” where it oversees Trump’s plan for Gaza, and that the White House is deeply involved in efforts to disarm Hezbollah and advance normalization between the Israeli Occupation and Lebanon. He adds that Trump has shown sustained interest in Syria’s political transition, lifting sanctions, urging Congress to support reconstruction, and pushing “Israel” to engage in border-security talks with Damascus.

A New Strategy

While Trump’s new national security strategy narrows America’s focus on the Middle East, it also signals a broader shift toward reducing Washington’s global footprint and turning inward. The document places new emphasis on domestic and regional priorities such as homeland security, immigration, and a renewed push to consolidate influence across the Americas.

It also frames Europe as a continent facing what the Trump administration calls a civilizational erasure driven by migration. According to the administration’s view, Europe risks losing its cultural contours within two decades if it continues on its current path. The strategy argues that the United States should help Europe correct course by supporting anti-immigration and nationalist parties. The New York Times reported this framing on December 5, 2025.

The goals, however, sit uneasily with one another. The administration insists it wants to scale back foreign entanglements and hold NATO allies responsible for their own security, yet its current policies remain deeply embedded in global flashpoints.

As Washington signals a lighter footprint in the Middle East, the strategy assigns clear priority to the Western Hemisphere. It explicitly backs the ongoing military operation President Trump is directing in Venezuela, framed as a campaign to combat drug trafficking in the Caribbean.

The document also revives the Monroe Doctrine in a more interventionist form. It calls for an expanded military presence, the option of ground operations, interference in European elections, and open support for populist right-wing leaders. These moves blur the line between retrenchment and renewed interference abroad.

The strategy defines five core foreign policy interests, placing the Western Hemisphere at the top. It openly pledges what it calls the Trump addendum to the Monroe Doctrine, paired with a promise to help allies preserve Europe’s security and restore Western identity.

It states that American predominance in the Western Hemisphere is essential to national security and prosperity. It warns that alliances and aid will depend on partners reducing hostile foreign influence, beginning with control over military sites, ports, and critical infrastructure and including restrictions on the purchase of strategic assets.

Analysts noted that China is no longer described as the primary threat or the most consequential challenge. This marks a clear downgrading of its strategic weight compared with earlier policy documents. Even so, China is still treated as an economic rival and a destabilizing force in global supply chains, and the strategy insists the United States must prevent Beijing from achieving regional dominance that could undermine the American economy.

Despite rising tensions over Taiwan, the document treats China as a managerial problem to be handled, not an ideological enemy to be defeated. The same contradiction appears elsewhere. The strategy calls for an economic coalition to counter China, yet the administration continues to wage trade battles against its own partners while demanding that they shoulder larger defense burdens within NATO.

European politicians have bristled at Washington’s tone, even as their governments remain heavily dependent on American military support and struggle to rebuild their own armed forces in response to the Russian threat.

A Reuters report on December 5 described the new strategy as a revival of the Monroe Doctrine and a sharp rebuke to Europe. The report warned that the shift could reignite anxiety among allies and adversaries alike as the United States reassesses its relationship with Europe. Some European commentators said the strategy echoes the rhetoric of far-right parties that have become major opposition forces in Germany, France, and elsewhere.

Reuters also noted that Washington expects Europe to assume most of NATO’s traditional defense responsibilities, including intelligence and missile capabilities, by 2027. European officials called the deadline unrealistic.

Sources

- The National Security Strategy: The Good, the Not So Great, and the Alarm Bells

- Trump strategy document revives Monroe Doctrine, slams Europe

- How Christian Nationalism Is Shaping Trump’s Foreign Policy Toward Africa

- Trump Administration Says Europe Faces ‘Civilizational Erasure’

- Trump reveals what he wants for the world

- U.S. National Security Strategy 2025: The Return of Realism

- Unpacking a Trump Twist of the National Security Strategy