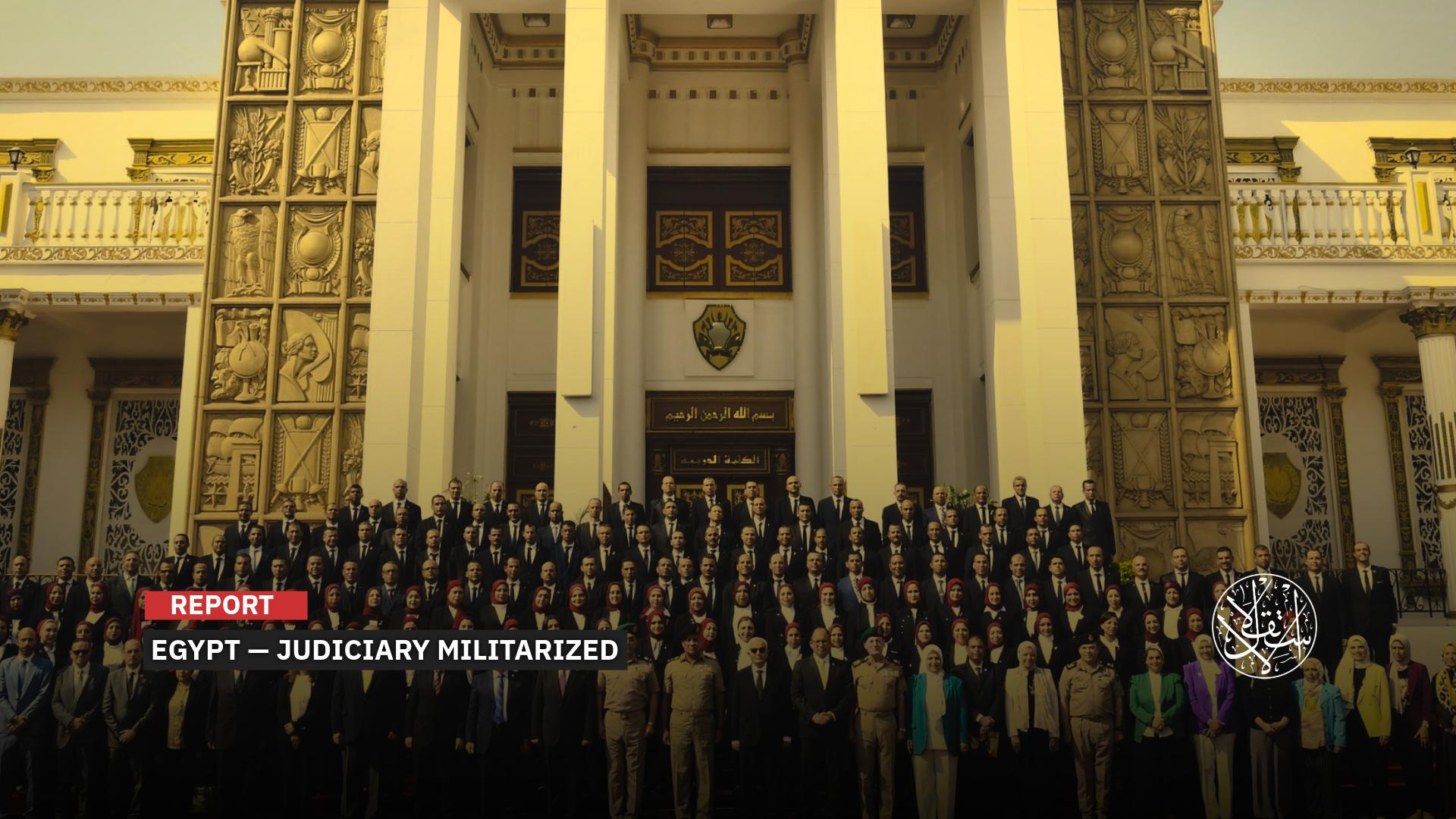

After Years of Ruling to His Whims, Egypt’s Judges Are Caught Beneath el-Sisi’s Iron Grip

Promotions, under el-Sisi’s directives, will be limited to those who have completed advanced courses at the military academy.

Egyptian regime President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi is seeking to fully subjugate judges through different and successive methods, the latest of which is his directive assigning the military academy responsibility for overseeing their appointments and promotions.

This move has prompted the Egyptian Judges Club to place its members on continuous alert and in permanent session since January 21, 2026, citing a “grave matter” affecting judicial affairs and the independence of the judiciary.

This step is not el-Sisi’s first intervention in judicial affairs. Militarization has been underway for years through a sustained methodology, implemented in successive stages, amid a striking silence from judges.

The latest approach is merely the culmination of this methodology, raising questions about the reasons behind judges’ silence in recent years, during which el-Sisi sought to bring them fully under his control.

Why have they moved now, and can their action disrupt this ongoing methodology after most of them participated in the 2013 coup, tailored laws to serve the authorities, remained silent over their appointment by the head of the executive branch instead of an election among themselves, and accepted receiving military training at the army academy?

New Directives

Simultaneously with intensive propaganda broadcast by media outlets owned by the intelligence company (United Media) portraying the “paradise” of training state employees at the “military academy,” el-Sisi’s chief of staff, Counselor Omar Marwan, held a meeting with the heads of judicial bodies to deliver new presidential directives.

The “directives” transfer the authority to select and appoint members of the prosecution and new judges from those judicial bodies to the military academy, which has already begun controlling the appointment of all positions in Egypt after holding military courses for them.

Because of this approach, which represents a troubling culmination of a sustained methodology to “militarize the judiciary,” like other sectors of the Egyptian state, and is expected ultimately to target the al-Azhar institution as well, and due to the media promotion of the academy as “a pride for all Egyptians,” judges have finally moved, though belatedly.

The “culmination of the militarization of the judiciary,” as conveyed by Omar Marwan to the heads of the Court of Cassation, the State Council, and the Administrative and State Litigation authorities at the Ettehadia Palace, was described as “presidential directives.” These directives stipulated, “Transfer all procedures for appointing members of judicial bodies, including members of the Public Prosecution, to the military academy, instead of the High Judicial House and the offices of other judicial bodies and authorities.”

This was revealed by a deputy of the Court of Cassation, and two deputies from the State Litigation and Administrative authorities, to the investigative platform Mada Masr on January 21, 2026.

As a fait accompli, Marwan, citing el-Sisi, informed them that the selection of judges for the 2022 law cohort, whose appointment procedures began in February 2023, would be canceled, and candidates would be reselected for appointment by the military academy.

It was also decided to cancel preliminary interviews for applicants to the Public Prosecution for the 2024 cohort, which had begun on January 10, 2026, before members of the Judicial Inspection, with the remaining procedures to be completed at the academy.

These include questions about family background, measurements of height and weight, and military training, which previously led to the exclusion of 179 imams in earlier military tests.

Under the new directives, the appointment mechanism will change fundamentally. Judicial bodies will no longer be responsible for selecting candidates, administering legal tests, and referring successful candidates to the military academy for the qualifying course.

Instead, all appointment procedures will begin and end within the academy itself, according to the three advisers, who explained that law school graduates will first go to the military academy for medical, physical, and psychological examinations, verification of height and weight ratios, and security clearances.

After passing these stages, the names of accepted candidates will be referred to the Supreme Judicial Council, which will test them in legal subjects through the “Septet Committee” composed of the seven most senior advisers in each judicial body. Each candidate will be assigned a score on the legal test.

The judicial committee then sends candidates’ scores to the military academy, which conducts the final evaluation of each applicant based on all test results and prepares a final list of those approved for appointment.

This list is then submitted to the Supreme Judicial Council for ratification.

In the final stage, the academy forwards the list of graduates to the president, who issues the presidential decree appointing them.

Judicial sources told the “Do Not Believe” platform that the decision will extend to cancel the role of the Supreme Judicial Council in appointments and promotions across judicial bodies, restrict promotions to those completing advanced courses at the military academy, and abolish the Appointments Department at the Public Prosecutor’s office, starting in 2027.

Ironically, the meeting convened by the Egyptian Judges Club on January 21, 2026, saw an unprecedented turnout of judges, the largest since the 2013 meeting led by Ahmed al-Zind to protest the dismissal by the late President Mohamed Morsi of former Prosecutor General Abdel Meguid Mahmoud.

The club witnessed historic attendance, with hundreds present, main halls filled, and video conferencing used in several locations to broadcast the proceedings.

Attendees agreed on the necessity of resisting the directive and scheduled a general assembly for February 6, 2026, to allow negotiation in hopes of reversing the final stage of militarization.

Space was left for negotiation with those managing the crisis, including direct meetings between the Supreme Judicial Council and el-Sisi’s chief of staff and former Justice Minister Omar Marwan, and between the head of the military academy, General Ashraf Salem, with Justice Minister Adnan Fanjari present, in an attempt to reverse the decision.

The statement of the Judges Club, circulated internally within their private groups, included decisive language such as: “Once the truth of what is being raised and circulated becomes clear, we will not hesitate, not an inch, to defend the judiciary, its independence, and the preservation of its authority,” and, “To unite, to rally, and to stand as one line, so that Egypt’s judiciary remains free, independent, and dignified.”

From Independence to Militarization

This is not the first time the executive branch has intervened in judicial affairs, drawing public criticism and concern within judicial circles.

The Egyptian regime has consistently pursued a “sustained methodology” to militarize the judiciary since 2013.

Three stages of militarization of the judiciary, judicial bodies, and judges can be observed in Egypt as follows:

Stage one: From 2013 to 2017, the “militarization of the judiciary” involved stripping civil courts of certain powers and transferring them to the military judiciary in order to suppress protests following the 2013 coup.

Stage two: From 2017 to 2023, this was the phase of “militarizing judicial bodies,” during which el-Sisi appointed the heads of these bodies to ensure control over courts and judicial institutions, preventing any objection to the systematic militarization.

Stage three: Ongoing since 2023, this is the phase of “militarizing the judges themselves,” through their training at the military academy, followed by transferring the authority for their appointments from judicial bodies directly to the military.

The militarization of Egypt’s judiciary began in 2013, when the country saw a systematic expansion in the use of military courts against civilians and a decline in the independence of civil courts, strengthening the role of the military within the judicial system.

This became part of a broader political-military control apparatus targeting both the civil judiciary and opponents, particularly Islamists, at a time when military courts had previously been used only in exceptional cases before 2013.

Between 2011 and 2012, during the transitional period following the 2011 revolution, the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces used military courts on a wide scale, with more than 11,000 civilians tried before military tribunals, according to human rights organizations.

After the military coup and the ouster of President Mohamed Morsi on July 3, 2013, and with the military assuming power, its role in all state institutions was reinforced, marking the beginning of a more aggressive phase of judicial militarization as part of its control over the judicial system.

The process began with the approval of the “Constitutional Committee,” formed by supporters of military rule, in December 2013, allowing rulings that permitted civilians to be tried in military courts under specific circumstances, effectively laying the groundwork for officially legislating judicial militarization, according to rights groups.

After formally taking power through engineered elections, President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi issued in October 2014 Law 136 on the militarization of the judiciary.

The law granted military courts the authority to try civilians for what were called “crimes against public and vital facilities,” a broad scope encompassing protests, demonstrations, and even social unrest, matters normally under the jurisdiction of civil courts.

According to human rights reports, more than 7,400 civilians were referred to military courts in the period following the law, facing multiple prison sentences in political, economic, and social cases.

In 2015, the law was widely applied, with civilians sent to military courts for reasons related to “demonstrations” or “disturbing public security,” drawing widespread criticism from rights organizations and judges.

During 2016, judicial militarization expanded into non-military spheres, with military courts used in cases such as Alexandria Shipbuilding Company workers, who were detained and tried militarily after protesting wages and working conditions.

By November 2021, judicial militarization was legally expanded, embedding provisions of the broad military law into existing civil legislation permanently, meaning that referring civilians to military courts was no longer temporary or exceptional but part of the established legal framework.

In March 2024, the legal basis for militarization was further reinforced through additional amendments expanding the powers of military courts, including the establishment of new “military courts of appeal” at the expense of the civil judiciary.

These amendments did not change the essence of judicial militarization but rather strengthened and consolidated the military court system as an alternative to civil courts for a wide range of cases, embedding the strategy legally and integrating it into the foundational legal framework.

The Beginning of Militarization

The phase of “militarizing judicial bodies” began with the issuance of Law No. 13 of 2017, amending the “Judicial Authority Law,” which granted broader powers to President el-Sisi in selecting the heads of judicial bodies, facing only weak opposition from some judges.

This approach was reinforced by a constitutional amendment in April 2019, passed through what rights organizations described as a fraudulent referendum and electoral manipulation, establishing the “Supreme Council of Judicial Bodies” under the presidency of the executive branch.

The amendment further formalized and “constitutionalized” the president’s authority to appoint heads of judicial bodies.

Judges’ groups pushed back, with the State Council Judges Club sending a memo to parliament on March 28, 2019, stating that the amendments “destroyed what remained of judicial independence, tore it apart, and handed it over to the executive branch,” and that they “went to extremes in undermining judicial independence.”

The 2019 constitutional amendments, approved by the House of Representatives and ratified by el-Sisi, allowed the president to appoint judges of Egyptian courts, eliminating the previous system in which the most senior judges automatically became heads of judicial bodies.

Until March 28, 2017, the established practice had been for each judicial body to appoint its oldest and most senior judge as head.

El-Sisi’s law placed the right to choose heads of judicial bodies in the president’s hands, selecting from three candidates nominated by the respective bodies, breaking with the traditional rule of seniority.

Some judges at the time noted that the law was intended to sideline advisers Yahya Dakroury, who had ruled the Tiran and Sanafir agreement void, and Anas Amara, the former first deputy head of the Court of Cassation, due to his decisions overturning death sentences based on National Security Agency reports.

In July 2019, Adviser Abdullah Askar took the constitutional oath as head of the Court of Cassation and the Supreme Judicial Council, the position of “chief judge of Egypt,” before President el-Sisi.

Judges regarded this as the “official end” of judicial independence, as the executive branch now appointed the head of the judiciary, ending the era in which judges themselves selected their chief based on seniority.

El-Sisi appointed Adviser Askar as head of the Court of Cassation despite his being fourth in seniority among the seven most senior judges at the court, in accordance with the constitutional amendments granting the president authority to select heads of judicial bodies from among the seven most senior members nominated by the high councils of those bodies.

El-Sisi also appointed Adviser Essam el-Minshawy as head of the Administrative Prosecution Authority, succeeding Adviser Amani al-Refai, bypassing six of her senior colleagues, as el-Minshawy ranked seventh in seniority.

Under the constitutional amendments, el-Sisi also appointed the attorney general, despite objections from judges during former President Mohamed Morsi’s rule, when the head of the Judges Club, Ahmed al-Zind, mobilized opposition and even sought U.S. intervention.

The appointments extended to the head of the Supreme Constitutional Court, Egypt’s highest judicial body, rather than confirming the appointment of its most senior adviser among the five most senior deputies of the court.

A New Phase

During the first ten years of military rule, from 2013 to 2023, the focus was on militarizing laws, increasing the involvement of military courts in civil affairs, and gradually sidelining civil courts and the ordinary judiciary from their jurisdiction.

But since April 22, 2023, a new chapter began in the militarization of judges themselves, following the judiciary, with the Cabinet (acting on el-Sisi’s directive) introducing an unprecedented requirement obliging all appointees across all state sectors, bodies, and authorities to complete a six-month qualifying course at the military academy in Cairo.

This included new appointees in various judicial bodies, whether in the Public Prosecution, the State Council, the Administrative Prosecution, or the State Litigation Authority.

Under this decision, the military academy began playing a central role in training and selecting personnel across state institutions, particularly those joining the diplomatic corps at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and new teachers entering the Ministry of Education.

The academy also provided training for Ministry of Transport employees and prepared newly appointed staff in judicial bodies and authorities, a move that drew widespread legal and human rights criticism, and even extended to training the legislative branch, including 391 members of the 2026 parliament.

On June 13, 2024, the military academy celebrated the graduation of the first cohort of new judges following a six-month military training program, drawing criticism from the Supreme Judicial Council because the training included physical and psychological tests unrelated to judicial competence.

Before the Cabinet’s decision, appointments to judicial bodies and authorities were governed solely by the Judicial Authority Law, specifically Articles 38 and 116, which outline the conditions for appointing members of judicial bodies and authorities.

These articles contained no requirement for new appointees to complete military training courses as a condition for appointment and set procedures entirely under the judiciary, free from executive interference.

Appointments within the judiciary continued according to these procedures until the introduction of the new requirement mandating the military academy course.

The move sparked outrage among judges, who at the time publicly rejected the decision of Prime Minister Mostafa Madbouly.

Under this system, candidates for the Public Prosecution are subjected to military training, disregarding the independent nature of a judge’s role, in an attempt to erase their sense of independence at the start of their judicial careers by training them militarily and placing them under generals’ authority.

Beyond militarization, judges complain of financial pressures and insufficient salaries, which have led to the resignation of skilled personnel, accumulation of family and psychological pressures on remaining staff, and the departure of others abroad, leaving the judiciary, particularly as more privileges are granted exclusively to the military and police.

The latest approach, representing the culmination of this sustained methodology, changes the mechanisms for appointments and promotions within the Public Prosecution and judicial bodies and assigns them to the military, in a final attempt to restructure the judiciary with a security and military imprint.

According to Nasser Amin, director of the Arab Center for Judicial Independence and Advocacy, this constitutes “a blatant violation of the Egyptian constitution, a direct assault on the principle of separation of powers, and a total subjugation of the judiciary to the executive branch, completely nullifying any real meaning of judicial independence under international standards,” speaking to the Do Not Believe platform.

Amin also described it as “a fully constituted crime against the judiciary in Egypt” because it “subjects judges or members of the prosecution to a military appointment or promotion track, or ties their professional future to an executive or security authority.”

Sources

- Tomorrow’s Judges Will Be Chosen by the Military Academy [Arabic]

- Judges Club Announces Permanent Session and Calls for Emergency Meeting over Grave Matter Affecting Judicial Independence [Arabic]

- Judges: Dozens of Recent Judicial Appointments Failed Military Academy Tests Due to Weight and Physical Fitness [Arabic]

- Emergency Meeting of “Judges of Egypt” to Reject Move to Transfer Appointments to the Military Academy [Arabic]