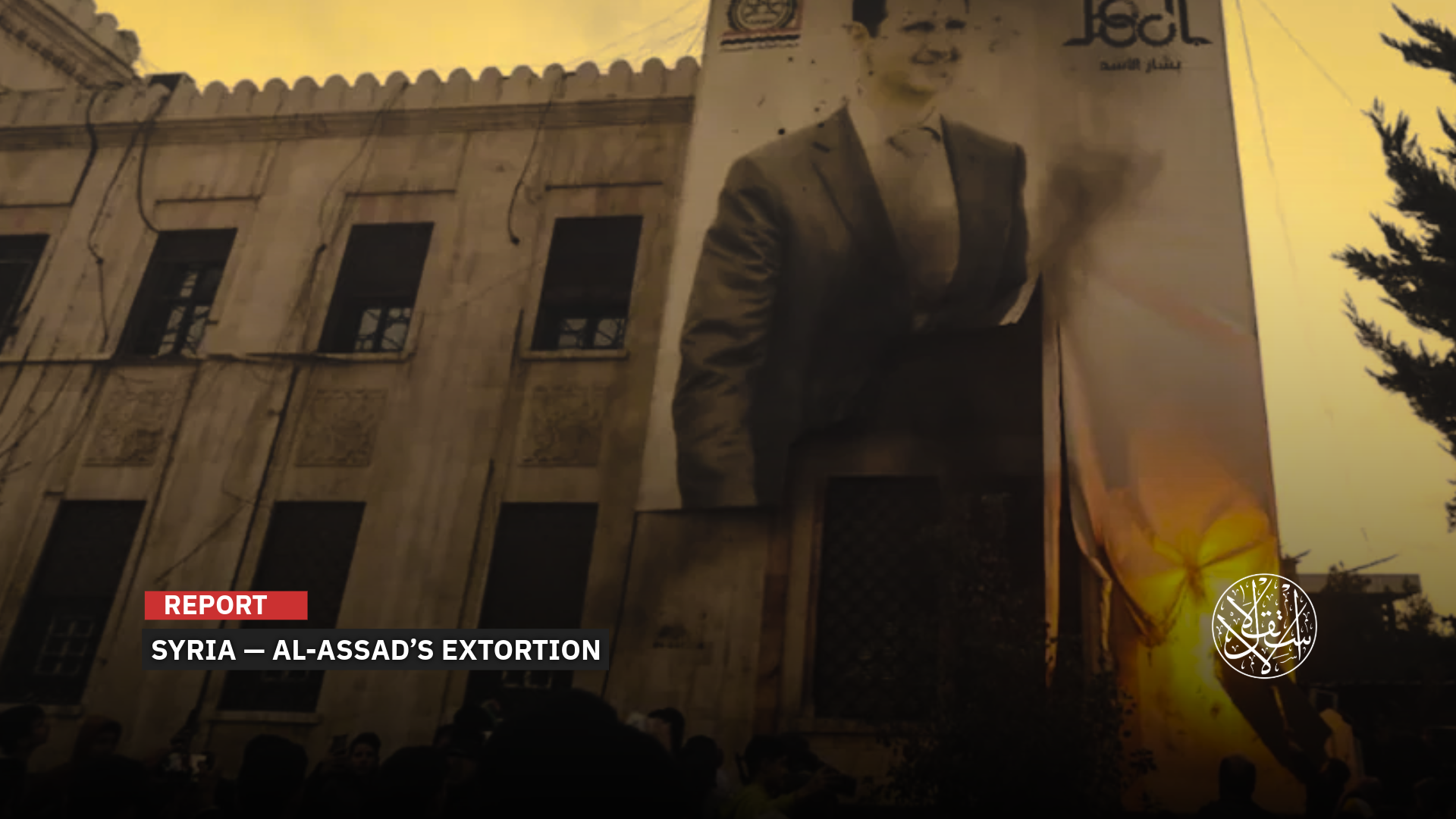

Pay a Bribe or Go to Prison: Testimonies Reveal al-Assad’s Extortion of Traders and Profit-Sharing Scheme

The levies imposed on traders varied according to their market influence.

The number of Syrian traders speaking out is growing by the day, exposing the massive financial extortion they suffered at the hands of the Republican Palace in Damascus under the former regime of Bashar al-Assad.

On December 7, 2024, just one day before the fall of al-Assad’s regime, the so-called “Secret Economic Council” inside the palace was operating actively, collecting financial levies from traders and businesspeople.

Palace Committee

The secret council was known as the “Palace Committee,” run by Asma al-Akhras, Bashar al-Assad’s wife, and staffed by a number of businesspeople.

She was assisted by Yasar Hussein Ibrahim, the palace’s financial director at the time, and Fares Nazim Class, secretary-general of the “Syrian Development Trust,” which Asma had launched in 2001.

The Palace Committee comprised several offices: the advisory office, the revenue office, the budget office, the strategies and studies office, the “Central Bank of Syria” office, the tax office, and the “security office.”

After al-Assad’s fall, some traders and businesspeople began to reveal the inner workings of the Palace Committee, and testimonies showed it was linked to multiple security branches.

Each security branch maintained a dedicated office whose sole purpose was to extort traders and businessmen, collecting levies under threat, with refusal often leading to imprisonment.

In an interview with Syria TV on January 29, 2025, Syrian industrialist Haitham Abo Shaar recounted the extortion carried out by the deposed al-Assad regime against traders.

He revealed that a Syrian trader seeking to import televisions for sale across the provinces was ordered by one security branch to pay $400,000 in levies set by the Republican Palace.

The trader refused, leading to his arrest in June 2024, a fabricated charge, and a seven-year prison sentence.

Abo Shaar noted that the unnamed trader was freed by rebels during the country’s liberation on December 8, 2024, after spending seven months in detention.

Syrian trader Anas Ajouri from Aleppo also spoke about the Palace Committee, stating that “its primary task was collecting funds to cover the war budget under the leadership of al-Assad family.”

Financial Extortion

In a podcast broadcast on August 8, 2025, Anas Ajouri shared testimony on the extortion of traders in Syria.

He said that the al-Khatib branch in Damascus, which was part of the General Intelligence Directorate, summoned traders and businessmen from across Syria and detained them for two weeks.

The detained trader was then handed over to a team from the Palace Committee, where they were questioned about the nature of their business, how they imported goods, and how they handled money.

Ajouri noted that during the rule of the deposed al-Assad, particularly after the revolution, laws were passed prohibiting transactions in U.S. dollars for prisoners who violated regulations.

“After negotiations with traders inside the security branch, they allowed the detainee to contact his family to pay a sum of money for his release,” Ajouri added.

According to Ajouri, the payment was deposited on behalf of the Palace Committee’s representative at the Central Bank of Syria.

Many traders fled Syria during al-Assad’s rule when they learned that their colleagues were being arrested by intelligence agencies, he said.

“The amounts collected in U.S. dollars varied depending on a trader’s market weight and financial standing,” Ajouri said.

Before arresting any trader or businessman, the Palace Committee conducted a comprehensive assessment of their assets to determine the amount of the levy, he explained.

According to Ajouri, “A money exchange office owner paid half a million dollars to secure his release,” adding that “there were traders and businessmen who refused to pay the levy and died inside intelligence detention cells,” without naming them.

Regarding his own experience, Ajouri recounted that in 2018 a Chinese phone company offered him the opportunity to import mobile phones into Syria.

He consulted a friend for a government license under al-Assad, and was warned not to proceed without permission from Khidr Ali Taher, known as “Abu Ali Khidr.”

“Abu Ali Khidr” was nicknamed the “Prince of Border Crossings” for his prominent role in smuggling between Syria and Lebanon, and also called “al-Ghawar” because he led a militia affiliated with the Fourth Division, headed by Maher al-Assad, Bashar’s brother, which controlled commercial and “humanitarian” crossings in Aleppo, Syria’s economic capital.

Numerous reports indicated that Abu Ali Khidr acted as the economic front for Asma al-Akhras.

Ajouri said he met Abu Ali Khidr’s son-in-law, Eehab Alraaee, in Damascus, who told him that if he wanted to enter the mobile phone import business, he could, provided he opened a company in Syria and gave a portion of the profits to Khidr.

However, Ajouri abandoned the idea after businessmen warned him that he risked assassination, as the trade was exclusively controlled by Abu Ali Khidr in Syria.

Al-Assad’s Share

In Syria, the security apparatus was at the disposal of businessmen who served as Bashar al-Assad’s economic front, overseen by his wife Asma.

According to many Syrian traders, Branch 215, the Military Security’s “Raid Unit” in Damascus, arrested any trader importing goods controlled by Abu Ali Khidr.

Branch 215 was nicknamed the “Syrian Holocaust” because it saw the highest number of deaths from torture among the security branches.

Meanwhile, the al-Khatib security branch imposed monthly payments on traders in Damascus and Aleppo to allow them to continue their business operations.

Within this context, Anas Taleb, a Syrian clothing manufacturer, told Al-Estiklal that “the al-Khatib security office in Aleppo demanded payments from gold traders, and anyone who refused was imprisoned to intimidate the others.”

“In the final years before Assad’s fall, the country was economically divided, and no trader or businessman could import certain materials or goods, which became monopolized by a close circle of al-Assad’s allies, including iron, aluminium, wood, sugar, and tea.”

“Every trader summoned to the security branches for financial extortion kept secret the amount paid to the Palace Committee for their release,” he added.

“After al-Assad’s fall, many traders broke their silence, revealing that they had paid hundreds of thousands of dollars, while some claimed they were abroad during their detention to avoid being re-arrested if they spoke out.”

“Since 2022, there has not been a trader or businessman in Syria who does not pay levies to the Palace Committee.”

“Traders in Syria, prior to Assad’s fall, had begun factoring these payments into the additional costs of importing raw materials due to sanctions on the country,” Taleb noted.

In other words, traders were forced to allocate a portion of their profits to the Palace Committee, effectively paying a “share to al-Assad,” to avoid arrest and continue operating.

“Traders also feared raids by the tax office under the Palace Committee, which inspected company and factory computers to assess production, sales, and exports, in order to impose special taxes,” Taleb added.