US Sanctions on Colombian Mercenaries: What Impact Will They Have on Sudan’s War?

The sanctioned individuals make up the network’s organizational and financial backbone.

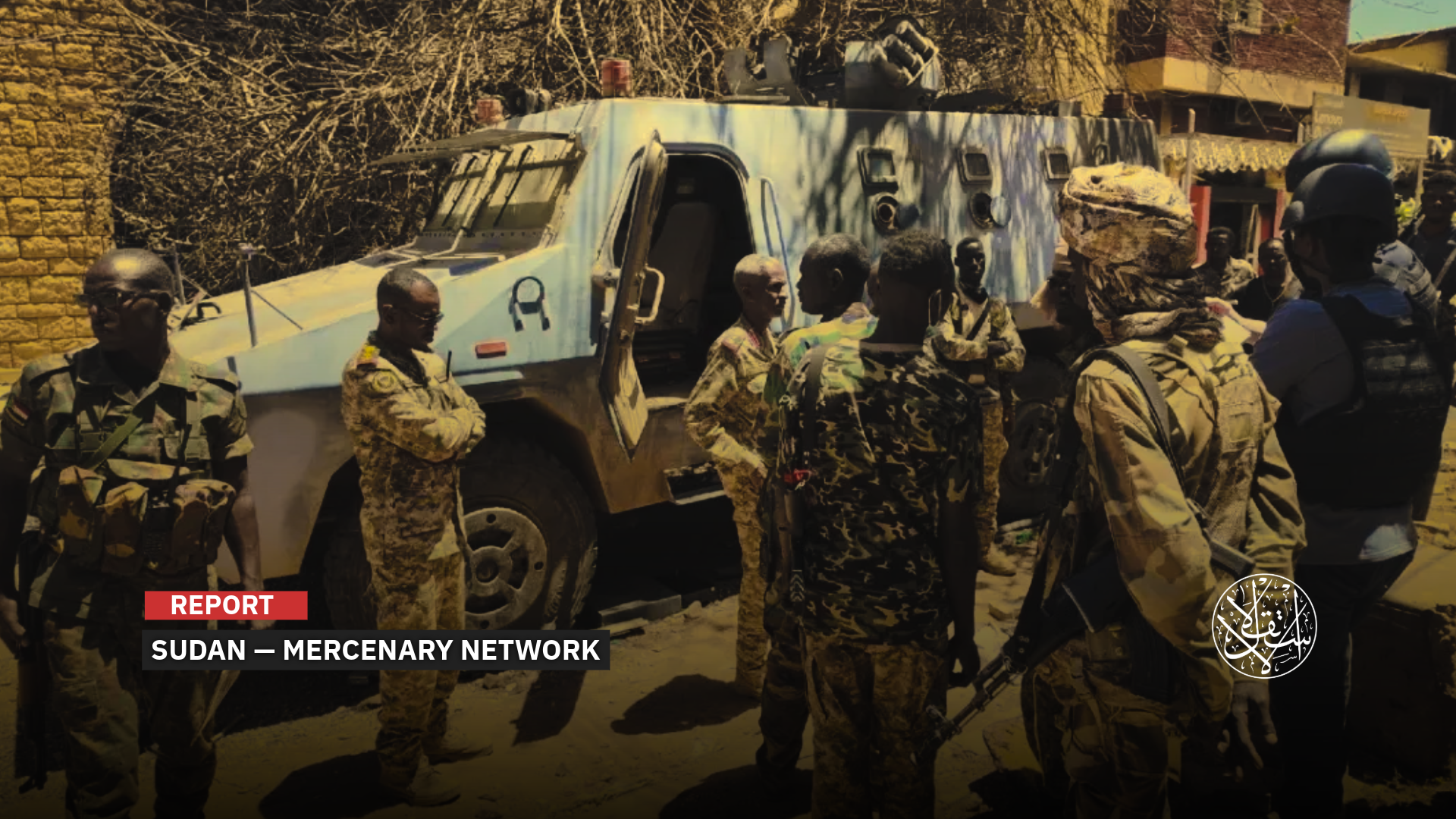

On December 9, 2025, the U.S. Treasury Department announced sweeping sanctions against an international network accused of recruiting fighters from Colombia and deploying them to fight alongside Sudan’s Rapid Support Forces militia.

The move was framed as part of Washington’s effort to choke off one of the most dangerous external sources of support for a civil war that has gripped the country since April 2023.

The measures, imposed by the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control, targeted four individuals and four entities described as the backbone of a transnational network that has played a central role in prolonging the conflict and deepening Sudan’s humanitarian catastrophe.

In this context, Colombia, a country long shaped by its own internal armed conflicts, has emerged as an unexpected source of mercenary fighters.

A Complex Network

While the news did not come as a complete surprise to those closely following the trajectory of Sudan’s conflict, it amounted to the first documented, official U.S. acknowledgment of the scale of the role played by mercenaries from Latin America, most notably former Colombian soldiers, in tipping the balance in favor of the Rapid Support Forces militia in decisive battles, particularly in Darfur and Khartoum.

The announcement also marked the culmination of a series of international investigative reports and field testimonies that, over the past two years, have traced the outlines of a complex network stretching from Bogota to Abu Dhabi, via Libya, and into Sudan’s battlefields.

Since the outbreak of war between the Sudanese army and the Rapid Support Forces militia, the country has become an open arena for undeclared regional and international interventions.

Some have taken a direct form, through weapons and financing, while others have relied on more intricate tools, including the recruitment of foreign fighters to serve as a quasi-paramilitary auxiliary force.

Within this context, Colombia, a country long known for its own internal armed conflicts, has emerged as an unexpected source of mercenary fighters.

Training Children

According to a statement by the U.S. Treasury Department, the network sanctioned has, since at least 2024, recruited hundreds of former Colombian soldiers, trained them, and transported them to Sudan to fight alongside the Rapid Support Forces militia. Their role went far beyond serving as infantry.

They were involved in operating heavy artillery, directing drones, and providing advanced tactical expertise, as well as training local fighters, including children, in combat.

John K. Hurley, the Treasury’s undersecretary for terrorism and financial intelligence, described the network as a stark example of the internationalization of Sudan’s conflict.

He said the Rapid Support Forces militia had repeatedly demonstrated a willingness to target civilians, including infants and children, and that supporting them through mercenary recruitment networks contributes to regional instability and creates fertile ground for the growth of extremist groups.

The U.S. sanctions included the freezing of any assets held by the designated individuals and entities within the United States, a ban on all financial and commercial dealings with them, and their inclusion on international sanctions lists that restrict their movement and their ability to operate within the global financial system.

Among the most prominent names cited in the statement, described as forming the organizational and financial backbone of the network, were:

Alvaro Andres Quijano Becerra, a retired Colombian army officer holding Colombian and Italian citizenship and based in the United Arab Emirates, who the Treasury accused of playing a central role in recruitment and the field deployment of fighters in Sudan.

The National Recruitment Agency, a Bogota-based staffing company co-founded by Quijano, identified as a hub for recruitment operations through job campaigns seeking drone operators, snipers, and translators.

Claudia Viviana Oliveros Forero, Quijano’s wife and the agency’s director, who oversaw the administrative and operational aspects of recruitment contracts linked to sending fighters to Sudan.

Mateo Andres Duque Botero, a dual Colombian and Spanish national who runs Mine Global Corp in Bogota, accused of managing and transferring funds to pay the salaries of Colombian fighters.

Global Staffing, now known as Talent Bridge, a Panama-based company that acted as an intermediary to conceal the National Recruitment Agency’s role in recruitment contracts and financial transfers.

Monica Munoz Ucros and the Colombian company Comercializadora San Benito, both accused of handling bank transfers connected to fighter salaries and covering logistical costs.

The UAE’s Role

The story of Colombian mercenaries in Sudan did not begin with the U.S. sanctions. It dates back to the early months of the war, when cryptic videos and photographs began circulating in the media and on social platforms, showing fighters speaking Spanish with a Latin American accent.

They appeared in areas far from the conventional frontlines, most notably in the Darfur region.

On December 12, 2024, the Wall Street Journal published an in-depth investigation based on mobile phone footage recorded in remote parts of Darfur.

The videos showed uniformed fighters displaying weapons and personal belongings taken from detainees who had been captured.

In one clip, the voice of an armed man can be heard examining the detainees’ passports, discovering that they were Colombian, before saying in Arabic tinged with a Zaghawa accent, “These are not Sudanese, they hold Colombian passports.”

The investigation, drawing on interviews with more than a dozen international officials and former Colombian fighters, confirmed that the men had been recruited during the first half of 2024 by a UAE-based company known as Global Security Services Group, headquartered in Abu Dhabi.

According to the newspaper, the company describes itself in official documents as the exclusive provider of private security services to the Emirati government, and lists sovereign entities among its clients.

Fraudulent Contracts

This was not the only account. In early January 2025, Sudanese outlet Ayin, which publishes in English, released a detailed investigation by the Colombian journalist Santiago Rodriguez that laid bare an international mercenary recruitment network targeting former Colombian soldiers and luring them through deceptive employment contracts.

The investigation reported that recruitment companies operating between Colombia and the United Arab Emirates, including the Colombian firm A4SI and Global Security Services Group, offered jobs ostensibly related to protecting oil facilities in the Gulf, with attractive salaries and conditions that appeared safe.

According to testimonies from the soldiers, however, once they arrived in the UAE they discovered that their true destination was Libya, and from there overland into Sudan, where they were instructed to take part in military operations alongside the Rapid Support Forces militia.

Rodriguez quoted one soldier as saying they had been misled about the nature of the assignment and suddenly found themselves on open battlefronts, with no real option to withdraw.

The reporting went beyond personal testimonies. It was backed by audio recordings, documents, contracts, photographs, and screenshots from WhatsApp groups used to coordinate the movement of the mercenaries.

The Dutch investigative outlet Bellingcat also tracked the movements of Colombian mercenary Christian Lombana Moncayo, who left Abu Dhabi on October 11, 2024, bound for Benghazi, before traveling overland into Sudan.

The Crimes in el Fashir

On the ground, Sudanese military sources have spoken of dozens of Colombian mercenaries killed in fighting in Darfur, while joint forces allied with the army announced that 22 of them were killed during fierce clashes.

The absence of official documentation, however, has raised questions about the true scale of the losses and prompted some journalists to suggest that the companies involved tightened secrecy measures and increased mercenaries’ pay in exchange for their silence.

The role played by these fighters reached its peak in el Fashir, the capital of North Darfur state, which endured a suffocating siege that lasted 18 months.

With the backing of foreign fighters, the Rapid Support Forces militia seized control of the city on October 26, 2025. What followed was a wave of widespread abuses, including the mass killing of civilians, ethnically motivated torture, and systematic sexual violence.

On January 7, 2025, the U.S. State Department announced that members of the Rapid Support Forces militia had committed genocide, the gravest legal designation applied since the start of the war.

The department said the targeting of civilians, including infants and children, the deliberate assault on women and girls, and the obstruction of humanitarian aid constituted a systematic pattern of crimes.

Against this backdrop, the Treasury Department’s sanctions amounted to a dual political and security message. On the one hand, they formally acknowledged the existence of a cross-border mercenary network operating in support of the Rapid Support Forces militia.

On the other, they applied pressure on regional actors accused of facilitating this support, without naming them directly.

Massad Boulos, the U.S. president’s senior adviser for Arab and African affairs, said the United States was holding perpetrators of atrocities in Sudan to account, calling for the acceptance of a humanitarian truce and an end to external support from transnational networks of killers.

The State Department said the sanctions disrupted a key source of external supply for the Rapid Support Forces militia and that Washington would coordinate with countries in the region to end the atrocities and restore stability.

It also reaffirmed its commitment to the principles set out in the joint statement issued on September 12, 2025, which called for a three-month humanitarian ceasefire followed by a transitional process leading to an independent civilian government.

Partial Sanctions

The Sudanese researcher Mohamed Nasr told Al-Estiklal that the U.S. sanctions imposed on the Colombian mercenary network, while significant, remain an incomplete and truncated step unless responsibility is also directed at the United Arab Emirates and its government, which he described as the actor that financed, organized, and managed the network from the outset.

Nasr argued that it makes little sense to sanction operational entities or intermediary links while ignoring the UAE, which he said brought in the mercenaries, transported them, and provided them with the financial, logistical, and political cover to “burn Sudan.”

He said field evidence and international journalistic investigations have left little room for doubt that the UAE played a central role in recruiting Colombian mercenaries through affiliated security companies, using them as a tool of proxy warfare in support of the Rapid Support Forces militia.

Ignoring this role, Nasr added, amounts to political complicity rather than an intelligence failure, warning that talk of cutting off the sources of the war loses credibility if accountability does not extend to the sponsors and financiers.

He stressed that transnational networks do not operate in a vacuum, but move under the protection of states and clearly defined policies, and that placing blame solely on brokers or executors in practice shields the real actor from accountability.

Nasr concluded that the war in Sudan has long ceased to be an internal affair and has instead become an international proxy war, directed from abroad and carried out with foreign tools, while Sudanese civilians are left to face killing, starvation, and collapse.

He warned that any international approach that fails to place the UAE’s role under direct scrutiny would amount to a political continuation of the killing machine, rather than a serious attempt to stop it or to achieve peace and justice.

Sources

- Washington criticizes the Rapid Support Forces and imposes sanctions on their backers [Arabic]

- US sanctions target a network “recruiting Colombian fighters on behalf of Sudan’s Rapid Support Forces,” as the United Nations voices concern over the deteriorating situation in Kordofan [Arabic]

- Sudan says army destroys Emirati aircraft, killing 40 mercenaries [English]

- Sudan accuses the UAE of funding Colombian mercenaries to fight alongside the RSF in civil war [English]

- Sudan: 300 Colombian contractors "trapped" in the conflict