The Shadow Alliance: How Abu Dhabi Is Leveraging Europe’s Far Right Against Muslims

A network of 330,000 accounts tied to the UAE generated over 720,000 online actions targeting Muslims in Europe.

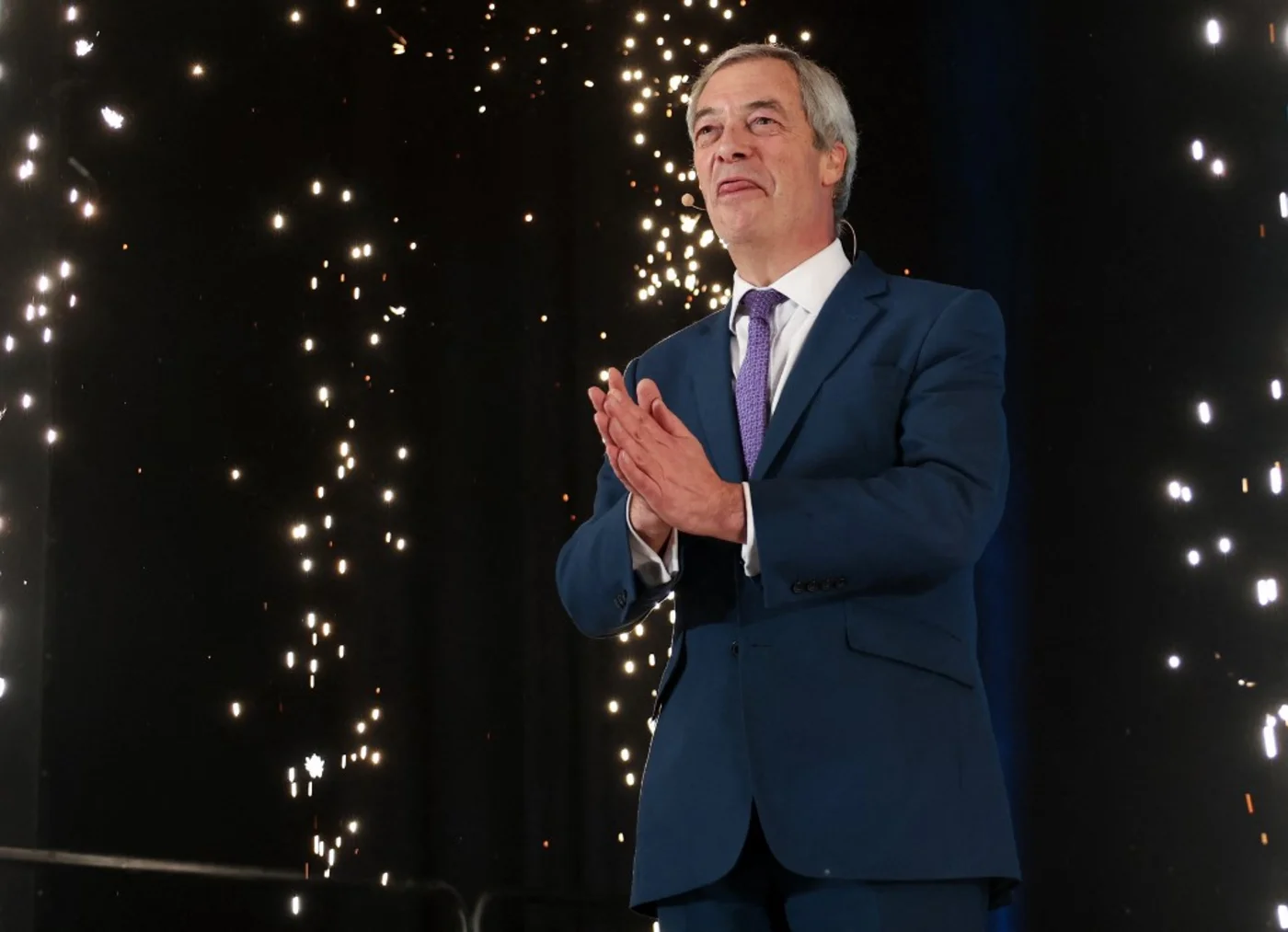

On an evening in January 2026, atop the luxury Ritz-Carlton hotel in Dubai, Nigel Farage, leader of Britain’s far-right Reform UK party, addressed a gathering of about 80 figures from the Emirati elite, among them Sultan Ahmed al Jaber, the UAE’s minister of industry and advanced technology.

In a cordial tone laden with political overtones, Farage told the audience, “We have a lot to learn from you, my dear sirs, we recognise you are our friends.”

He then went beyond polite pleasantries, speaking of a “post-Brexit London” and a “Reform London” that “will not forget its friends,” before acknowledging that such closeness might strike some as unusual.

He was quick, however, to justify it by pointing to what he described as common ground between the two sides, a shared stance against what they both refer to as “political Islam.”

For observers, the scene was not merely a protocol moment or a courteous speech at a closed-door meeting. Rather, it reflected a deeper shift in the UAE’s network of relationships in Europe, one increasingly oriented toward the rising forces of the far right in more than one European capital.

A Shocking Document

A few days later, on January 28, 2026, the French magazine Intelligence Online, which specializes in intelligence and security affairs, published a lengthy report revealing unprecedented details about the mechanics of this rapprochement, its limits, and even the risks as perceived by decision-makers in the UAE themselves.

According to the report, the magazine reviewed minutes from internal discussions concerning potential cooperation between the Polish platform Visegrad24, known for its wide digital reach and its ties to far-right milieus in Central and Eastern Europe, and the UAE Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

These discussions focused on supporting Abu Dhabi’s narrative in the West, particularly around combating what it describes as “radical Islam,” and presenting the UAE as a model of stability and counterextremism.

The significance of the documents, however, lies not merely in the existence of communication channels, but in how this alignment is being managed.

The documents reveal an internal memo issued by the Strategic Communications Department at the UAE Ministry of Foreign Affairs dated August 28, 2024, which concluded that the cooperation plan proposed by Visegrad24 was feasible and could help improve the UAE’s image among Western audiences.

At the same time, the memo warned that any direct and public cooperation could lead to diplomatic, political, or media complications with other countries, due to the platform’s aggressive rhetoric toward actors such as Qatar, Iran, and Russia, as well as its open adoption of the Israeli narrative in the war on Gaza.

This contradiction explains the ministry’s recommendation that any potential cooperation be conducted through an unofficial entity, relying on media fronts and individuals with no formal ties to the Emirati government.

Indeed, the documents point to the preparation of a list of six Emirati figures and influencers, including media advisers, columnists, researchers, and former officials, tasked with producing content that serves Abu Dhabi’s narrative and feeds platforms such as Visegrad24 with ready-to-publish material, ranging from post series to interviews and political analysis.

The documents also reveal that the Polish platform offered to produce two documentary films for Abu Dhabi, with telling titles, “The UAE’s Approach to Combating Radical Islam” and “The UAE as a Regional Peacemaker.”

The offer also included what the platform described as its ability to support public relations campaigns in European regions that typically receive limited attention, such as Central and Eastern Europe and the Baltic states.

According to the platform’s own promotion, its audience base consists of 38 percent in North America, 40 percent in Europe, and 8 percent in the Middle East, many of them in “Israel,” in addition to tens of thousands of journalists and influential figures.

The Far-Right Alliance

In practical terms, Intelligence Online notes that the contours of this cooperation are no longer confined to internal documents, but have begun to surface clearly in the content published across the platforms involved.

In December 2025, the Visegrad24 account reposted an old speech by the UAE’s foreign minister, Abdullah bin Zayed al Nahyan, dating back to 2017, in which he urged Europe to be wary of the Muslim Brotherhood.

The post was accompanied by a comment suggesting that the minister’s words “seem more prophetic today than ever before.”

At the same time, the account has increasingly aligned itself with Abu Dhabi’s positions on sensitive regional files, including the war in Yemen, control over Socotra, a hard line toward Iran, and advocacy for international recognition of Somaliland.

This digital presence has not been isolated from more direct political engagement.

Prominent figures from far-right currents in Britain and France have begun to visit the UAE more frequently, or to express open admiration for its political and security model.

Nigel Farage, leader of Britain’s far-right Reform UK party, praised the UAE in response to a report published by the Financial Times that revealed Abu Dhabi’s decision to halt funding for Emirati students at British universities, citing the influence of the Muslim Brotherhood in some educational institutions.

In France, Jordan Bardella, leader of the far-right National Rally party, reposted content supportive of the UAE and had previously visited Abu Dhabi in June 2025, where he met with senior figures at the highest levels of power.

Although his office declined to comment on the nature of those meetings, the frequency of such visits and statements reinforces the impression that channels of communication exist beyond the bounds of conventional diplomatic courtesies.

The Emirati wager on leveraging the rise of Europe’s far right appears to be expanding.

Abu Dhabi is no longer merely a backstage supporter, but an increasingly active player in the West’s narrative battles.

War of Narratives

In 2021, reports published by The European Microscope for Middle East Issues, a European research center that monitors how Middle East-related files play out within the European political and media space, revealed that the United Arab Emirates had provided financial and media support to a center operating in Austria.

According to those reports, the center has been accused of playing a central role in distorting the image of Arab and Muslim communities, not only in Austria but across several other European countries.

Based on monitoring by The European Microscope for Middle East Issues, the Documentation Center Political Islam in Vienna received prominent media coverage from Emirati outlets, foremost among them the news website Al Ain, which presented the center as a model to be emulated in combating extremist organizations.

Emirati media also promoted the idea of replicating its experience in other European capitals, including Berlin, should it prove successful in Austria.

The center was launched in August 2020, modeled on European institutions dedicated to documenting the far right, and claimed to focus on studying political Islamic organizations and analyzing their structures and methods.

Critics, however, argue that it has moved well beyond an academic research framework, taking on an inciting role that targets Muslim communities by promoting a generalized discourse that conflates religious identity with political extremism.

The European Microscope for Middle East Issues noted that Emirati media outlets devoted extensive coverage to the center’s activities and reports, in what it described as a coordinated effort to promote the institution and strengthen its presence within European public debate.

It also reported the existence of regular Emirati financial support for the center, through an annual budget, as part of what it characterized as controversial Emirati influence activities within Europe.

The Documentation Center Political Islam is headed by Mouhanad Khorchide, who is known for his opposition to political Islam movements and to legislation with Islamic references.

He is regarded, according to European sources, as one of the figures close to influential Emirati lobbying networks on the continent.

Khorchide also maintains close ties with Austria’s right-wing People’s Party, one of the pillars of the governing coalition, which has adopted a hard-line stance toward Islam.

In 2024, a scandal erupted in France that placed the United Arab Emirates at its center, after the French judiciary revealed suspicions of illicit financing operations carried out by external actors in favor of the far-right National Rally party, known for its openly hostile stance toward Islam and Muslims.

The investigation, launched by the Paris public prosecutor’s office, is linked to the presidential campaign of the party’s leader, Marine Le Pen.

According to observers, the case represents the second major scandal of this kind to implicate the UAE in Europe, following earlier files involving allegations of spying on European citizens, particularly members of Muslim communities, and smearing them under the pretext of pursuing the Muslim Brotherhood.

In the details of the case, the French television channel BFMTV reported, citing judicial sources, that the Paris prosecutor’s office had opened a judicial investigation into suspicions of illegal financing of Marine Le Pen’s presidential campaign.

The prosecutor’s office confirmed on July 9, 2024, that the investigation was initiated on the basis of a judicial referral issued by the National Commission on Campaign Accounts and Political Financing (CNCCFP), after it identified facts that could potentially constitute criminal offenses.

According to BFMTV, the commission clarified that it had referred these findings to the public prosecutor in accordance with its legal powers.

In this context, the commission submitted an official report to the Paris prosecutor’s office, pursuant to Article 40 of the law, concerning the accounts of Marine Le Pen’s election campaign.

This development has revived longstanding questions about the nature and objectives of any potential Emirati funding of far-right movements in Europe.

These suspicions intersect with reporting published by the French investigative outlet Mediapart on October 21, 2016, which pointed to efforts by the National Rally to secure funding from the UAE to support its electoral campaigns, attributing this at the time to what it described as a “shared battle” between the party and Abu Dhabi against so-called “Islamist terrorism.”

The Swiss Right

On May 23, 2019, the president of the Islamic Council in Switzerland, Abdullah Nicolas, told Al Jazeera in an interview that “there are Arab countries, including the UAE, that incite against Muslims and provide information to far-right parties in Switzerland that adopt an anti-Islam discourse.”

His comments came in response to a question about whether there is a link between the ongoing campaign in some Arab countries to classify “political Islam” as terrorism, as seen in Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Egypt, and the rise of far-right rhetoric in Europe.

“I believe there is a trend in the region that may be more dangerous than it appears. These countries help the far right monitor information and incite European governments against those they consider a threat, such as the Muslim Brotherhood, by providing intelligence that prompts these governments to take action,” Nicolas said.

On the motivations behind UAE support for parties opposed to Islam and Muslims, the president of the Islamic Council in Switzerland said, “Because there is an agenda aimed at distancing Muslims from their adherence to this great religion, and pushing them to follow what resembles a new religion, tailored to European standards, far removed from the essence of Islam.”

“This is one of the methods used to create division among Muslims, by splitting them into so-called ‘good Muslims’ and ‘radical Muslims,’” he added.

Responding to a question about whether the UAE seeks to impose a false perception of Muslims and fund parties that oppose Islam and Muslims, Nicolas replied, “Yes. I have seen a document showing Emirati support for these movements, and for what are called new ideological schools seeking to change Islam, instead of supporting Muslims themselves.”

The Islamophobia Network

On January 28, 2026, the ICAD platform, which specializes in open-source investigations, revealed the monitoring of more than 330,000 accounts within a network linked to the UAE, which carried out over 720,000 digital interactions targeting Islam and Muslims in Europe, in one of the largest systematically documented incitement campaigns in this context.

The American magazine Foreign Policy had published a report on March 29, 2019, attributing primary responsibility for the rise of anti-Islam sentiment, or so-called “Islamophobia,” in the West to certain Arab regimes, notably the UAE.

The magazine linked this to the cooperation of these regimes with far-right parties in several European countries, aiming to cement narratives that serve the survival of their authoritarian systems by portraying political Islam as a comprehensive threat to global security and stability.

Foreign Policy reported that three Arab countries, the UAE, Egypt, and Saudi Arabia, had provided direct or indirect support to far-right movements in Europe in recent years, in an effort to alarm Western governments about political Islam groups, especially after some of them came to power in Arab Spring countries following the 2011 uprisings.

According to the report, these regimes spend millions of dollars on research centers, think tanks, academic institutions, and lobbying groups to influence decision-making circles in Western capitals and to tarnish the image of local political activists who oppose them.

The magazine argued that the “counter-extremism” agenda provided the perfect cover to market this narrative, granting it an acceptable moral and security justification in the West.

In this context, Foreign Policy cited a statement by UAE Foreign Minister Abdullah bin Zayed al Nahyan to the American channel Fox News, made a month after a public discussion in Riyadh in 2017, in which he said, “The ceiling of our discussion is extremely low when we talk about extremism.”

“We cannot accept incitement or financing. For many countries, terrorism is defined as bearing arms or terrorizing people. For us, it goes far beyond that,” he added.

The magazine concluded its report with a warning about the serious consequences of politically backed Islamophobia, noting, “Words are not cheap; the events in New Zealand have shown that inciting rhetoric can cost innocent lives.”