Europe Maps Alliances to Fend Off Trump’s Tariff Hammer

The European Union has recently struck landmark trade deals with major blocs and countries.

Europe is experiencing an accelerated push to diversify its global trade partnerships, amid rising tensions with the United States, fueled by President Donald Trump’s threats to take control of Greenland, which belongs to Denmark, and his continued policy of imposing tariffs on Europe.

Against this backdrop, the European Union has recently concluded what have been described as historic trade agreements with major blocs and countries, including the Mercosur group in South America and India, alongside signs of cautious engagement with China.

These moves come as part of broader European efforts to reduce economic dependence on a single partner and to strengthen the autonomy of its trade decision-making.

Trade Agreements

The European drive to diversify trade partners has translated into concrete steps, most notably the conclusion of a free trade agreement with the Mercosur bloc in South America after 25 years of stalled negotiations.

On January 17, 2026, European officials and Mercosur leaders signed the agreement in Paraguay’s capital, Asuncion, making it the largest trade deal in the European Union’s history.

The agreement aims to reduce tariffs and boost trade flows between the two sides, though it is still awaiting ratification by the European Parliament and the legislatures of Mercosur member states.

European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen praised the deal, saying it “chooses fair trade over tariffs” and lays the foundation for the world’s largest free trade area.

The agreement is expected to remove more than €4 billion a year in tariffs on European exports, particularly in the automotive sector, while opening markets that include more than 700 million consumers.

In the same vein, the European Union successfully concluded negotiations in late January 2026 on a free trade agreement with India, described as the “mother of all deals” because of its sheer scale.

Although it is less comprehensive than some other EU agreements, excluding sensitive sectors such as automobiles and government procurement, it delivers wide-ranging tariff reductions between two markets with a combined population of about 2 billion people.

The EU expects the agreement to help double its goods exports to India by 2032, while saving around €4 billion in tariffs.

European efforts have not been limited to India and Mercosur. In early 2025, Brussels revived a modernized agreement with Mexico, updating a partnership that spans decades.

It also concluded negotiations with Indonesia in late 2025 and is accelerating talks on a new deal with Australia, which is expected to give Europe broader access to strategic minerals, most notably lithium.

This rapid pace of trade deal-making is framed as a European precautionary response to the policies of U.S. President Donald Trump, with the European Commission openly acknowledging that the agreements are designed to offset the impact of American tariffs.

Trump’s recent policies have sparked widespread frustration across Europe, pushing the bloc to take tangible steps to end its economic dependence on a single partner.

Opening to China

Alongside these partners, European leaders are adopting a pragmatic approach based on cautious engagement rather than a rupture with China, despite persistent political differences between Europe and Beijing.

At the World Economic Forum in Davos in January 2026, French President Emmanuel Macron surprised the audience with a conciliatory message toward Beijing, saying that China was “welcome” economically in Europe, provided it increases the volume of direct Chinese investment in strategic European sectors.

Macron stressed that China should also contribute to technology transfer, rather than merely flooding European markets with subsidized or low-quality products.

Macron’s remarks came amid sharp criticism of the U.S. approach, as he accused Washington of seeking to weaken Europe through one-sided trade agreements and an “endless accumulation of new, unacceptable tariffs,” particularly when used as leverage that undermines European sovereignty, an apparent reference to the Greenland issue.

Macron’s tone aligns with a broader trend in Brussels and major European capitals toward what the European Commission describes as “de-risking” — reducing strategic dependencies on China without full decoupling — according to statements by Commission President Ursula von der Leyen.

Speaking before the European Parliament, von der Leyen said Brussels was ready to build a “more balanced and stable” relationship with China, based on a principle of “no naivety” and the protection of European interests in the absence of reciprocity, while keeping the door to cooperation open.

This European consensus against severing ties with China is rooted in economic realities.

Trade between the European Union and the United States reached approximately €873 billion in 2024, compared to €736 billion with China, which accounts for roughly 15 percent of the EU’s total global trade.

Against this backdrop, Europe recognizes that a complete break with the world’s second-largest economy is not a practical option.

Instead, it seeks to rebalance the relationship by diversifying supply chains and reducing dependence in sensitive sectors such as semiconductors and raw materials, while maintaining open markets and cooperation in areas of mutual benefit.

On the ground, this cautious opening toward China has translated into active diplomacy and high-level visits in recent years.

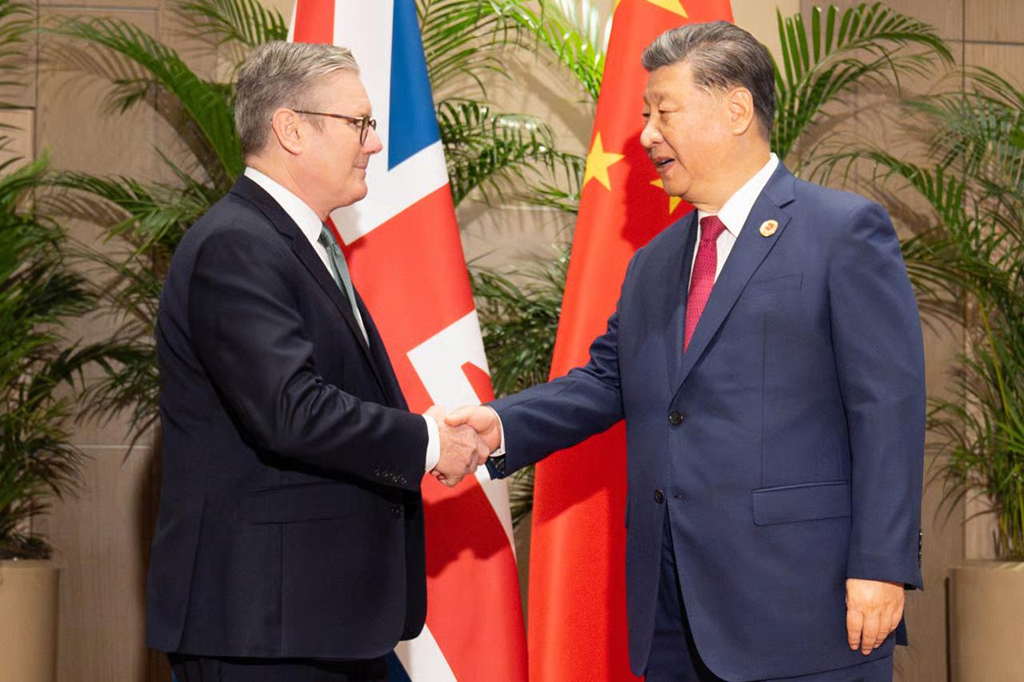

On January 28, 2026, British Prime Minister Keir Starmer arrived in Beijing for talks with President Xi Jinping aimed at improving bilateral relations, marking the first visit by a British prime minister to China since 2018.

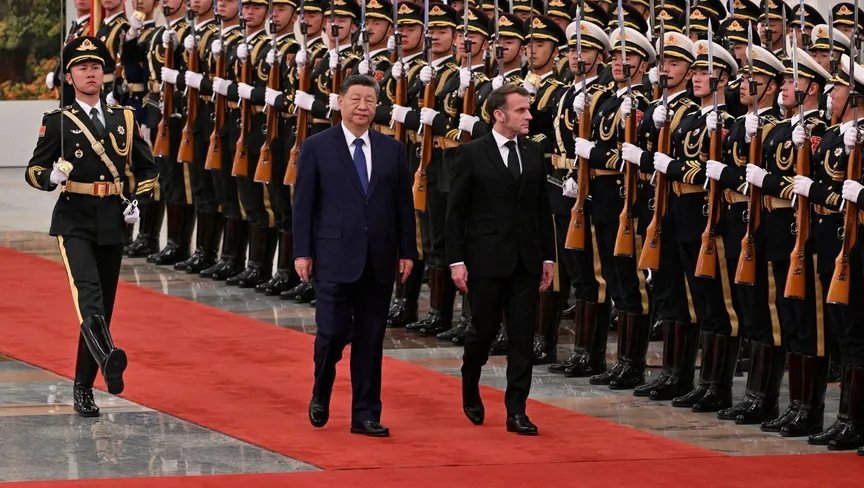

French President Emmanuel Macron also made an official visit to Beijing in December 2025, his fourth, with the stated goal of “addressing global trade imbalances.”

He was preceded by Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sanchez in April of the same year, on his third visit to China in three years, seeking to “deepen economic and political relations” between the two sides.

A Rising Power

Europe today finds itself facing a sharply polarized global landscape, caught between a traditional ally, the United States, whose trade policies have increasingly drifted away from multilateral frameworks, and a rising power, China, with which it has political differences but views economic cooperation as increasingly indispensable.

In this context, Europe is pursuing a pragmatic middle-ground approach aimed at widening its range of options by forging trade partnerships with new powers and markets, while at the same time maintaining balanced relations with both East and West.

European Council President Antonio Costa summed up this approach by saying that the agreement with the Mercosur bloc, along with other deals, “will help our two blocs navigate a stormy global political environment without abandoning our values.”

Speaking about the recent agreement with India, Costa said the deal “has great economic value, but perhaps more important is the message it sends,” stressing that “it is important, indeed essential, to provide a degree of certainty that favors cooperation over confrontation,” in a clear reference to the policies of U.S. President Donald Trump.

He added that “when global economic factors multiply and disrupt international trade,” trade agreements become a necessary tool for “stabilizing trade relations.”

Razan Shawamreh, a researcher specializing in Chinese affairs, argues that European countries have recently begun to view Beijing as a tactical card in their dealings with Washington under the Trump administration.

Shawamreh told Al-Estiklal that “the policies of the Trump administration are alienating and undermining trust among European allies, especially after the imposition of tariffs. As a result, Brussels has started to broaden its options based on the logic that if you want something from Washington, you have to go to Beijing.”

On whether Brussels sees Beijing as a substitute for Washington, Shawamreh explained that “the European Union is fundamentally the product of American support following World War II, so the idea of replacement is entirely off the table. What is happening is no more than political maneuvering and an expansion of partnerships.”

“China is not an alternative to the United States for Europe, not commercially, not politically, and not militarily, because it does not possess the tools that could provide Brussels with elements of dominance or security guarantees,” she added.

“Europe and the United States have built deep alliances across multiple fields over many decades, whereas what China can offer remains largely confined to economic agreements, without any meaningful weight on the security front, which is the most important.”

“The dominant global economic institutions are American in character, which makes it difficult for Europe ever to become part of the Chinese economic system. Brussels primarily uses Beijing to pressure Washington and to send a message that it is not the only player in the world.”

“With a change in the current U.S. president, Washington’s foreign policy is likely to change, and Europe is betting on that. Today, it is diversifying its options, but it does not want to lose the United States, as it waits for the return of a democratic ally, or even a Republican one, that does not pursue Trump’s policies,” Shawamreh concluded.

Sources

- Costa to Euronews: A Trade Agreement With India Reinforces the EU’s Voice in a Multipolar World [Arabic]

- China, EU Must Oppose Tariff ‘Bullying,’ Xi Tells Spanish Prime Minister

- China Pitches Itself as a Reliable Partner as Trump Alienates U.S. Allies

- EU and Mercosur Sign Trade Deal After 25 Years of Negotiations

- EU Adds India in Rush for Trade Deals After Trump’s Return