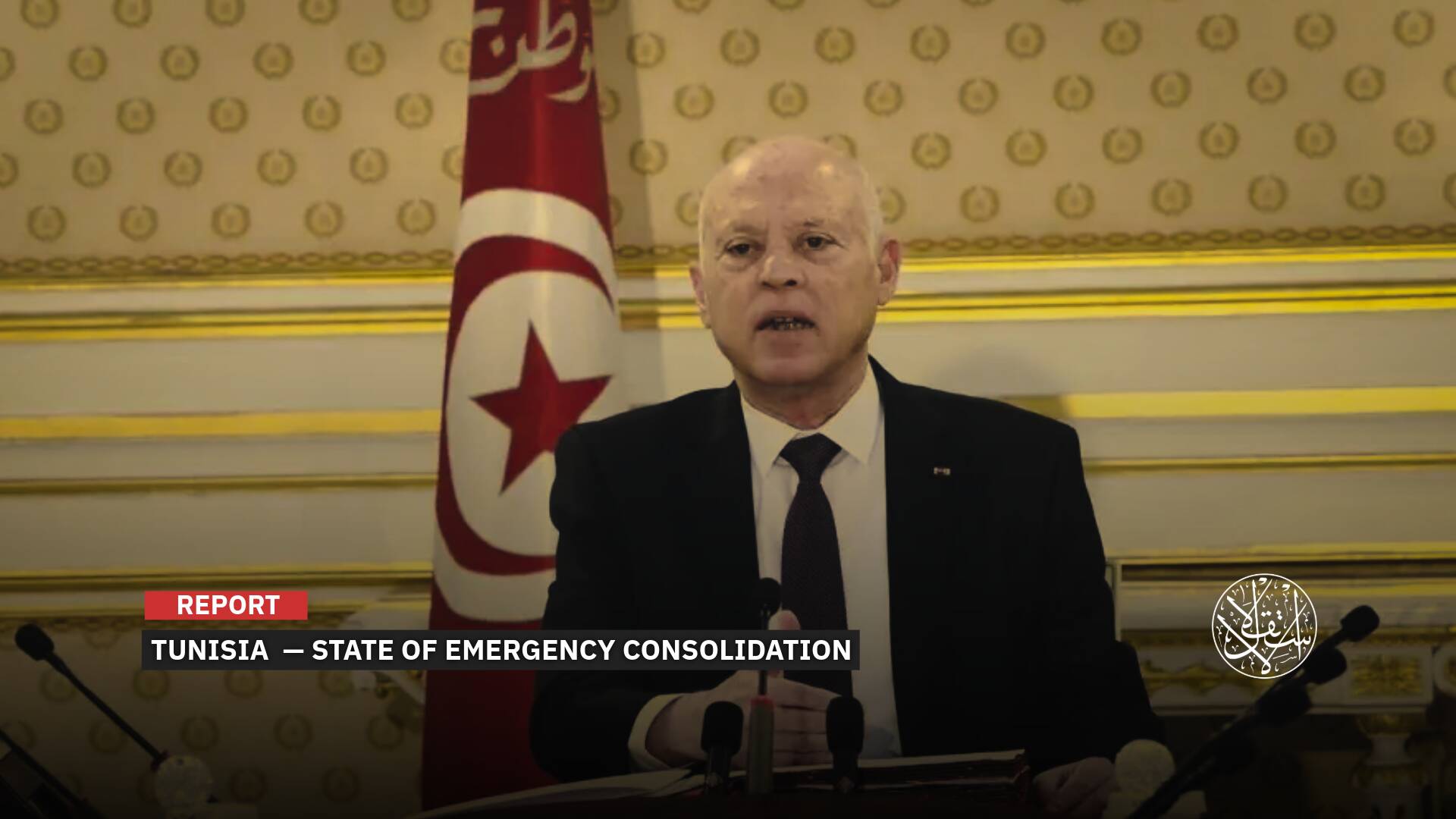

Mauritanian Rights Activist: Slavery Never Expires, Offenders Face Up to 10 Years Behind Bars (Exclusive)

“I visited every prison and reported critical issues to the authorities, including severe overcrowding.”

Ahmed Salem Bouhoubeyni, former head of Mauritania’s National Human Rights Commission (CNDH), says there’s no taboo in talking about slavery in the country. “Roughly 40 million people are still enslaved worldwide,” he told Al-Estiklal. “Even Europe built civilizations using humans as machines”

During an exclusive interview, Bouhoubeyni emphasized that Mauritania’s law now treats slavery as a crime that doesn’t expire, with harsh penalties of up to 10 years in prison.

Yet he stressed that international portrayals of slavery in Mauritania are often exaggerated. “There are no slave markets in our country, and it’s not true that 20 percent of Mauritania’s population is enslaved,” he said.

Turning to the state of the country’s prisons, Bouhoubeyni said severe overcrowding remains a major issue, and he has raised serious concerns with authorities.

Born in 1961, Bouhoubeyni is a former head of Mauritania’s National Order of Lawyers and a past president of the International Forum for Democracy and Unity, an opposition party in Mauritania. He served two consecutive terms as head of the CNDH, completing his second term earlier this year.

Democracy and Urgent National Issues

Mauritania’s democratic path has repeatedly included phases of national dialogue. How is the current situation assessed, especially in light of the latest political dialogue initiated by the president?

Democracy is based on a simple principle: a government elected through transparent elections should govern according to the program the people voted for. It does not make sense for the government to implement the opposition’s agenda, which lacks the voters’ mandate, as that contradicts the very essence of democracy.

The government must take full responsibility, addressing citizens’ problems, improving livelihoods and public services, and fostering national growth. Ultimately, the government will be held accountable for its successes and failures. At the same time, the opposition has a natural role: oversight, demanding more, and presenting alternatives.

It is normal for a president to consult various political forces on major national issues, as Mauritania’s current president has done since taking office. These consultations are positive but not binding; the government alone carries the responsibility for decisions and implementation.

On topics often raised in public dialogues, such as slavery or human heritage, they should not be included in broad political debates. There is no disagreement on slavery: everyone opposes it. What is needed are serious economic and social policies to address its effects, with the opposition monitoring and demanding more.

Regarding human heritage, a specialized government committee has been working on this for over a year, and it is better left in that institutional framework rather than debated by multiple parties with conflicting views that could hinder progress.

Dialogue is quite important, but it should not blur roles or mix agendas. In democracy, the government governs and the opposition opposes, and each is responsible for its own performance.

Which sectors need more government attention: justice, education, or others?

Justice comes first as the foundation of the state. We cannot speak of real development or democracy without an independent, effective, and swift judiciary that reassures citizens and guarantees their rights. Education follows as the backbone of any national project.

Without high-quality, unified education, human development and social cohesion are impossible. Social policy comes third, focusing on equality of opportunity and reducing disparities through fairer economic measures targeting vulnerable populations and opening opportunities for youth employment and integration.

These sectors are interconnected: justice builds trust, education builds capacity, and social policy ensures fairness. Without all three, Mauritania cannot achieve the aspirations of its people.

Clear government vision is essential. Mauritania faces significant challenges but also enormous opportunities thanks to its strategic location and diverse resources. A clear vision is needed to turn these challenges into real gains for Mauritanian citizens.

Human Rights Commission and Pending Challenges

You served two consecutive terms as head of Mauritania’s National Human Rights Commission. What does the commission need or lack?

I served a second term as head of the National Human Rights Commission over the past six years, and it was a remarkable period, full of challenges and achievements. The greatest challenge was reconciling the commission’s dual nature as a public advisory body to the government while maintaining independence. I believe we succeeded in achieving this difficult balance.

We worked on sensitive human rights files, and rather than limiting ourselves to futile debates, we adopted a transparent, field-based methodology in partnership with the United Nations, the European Union, the United States, and accredited embassies in Nouakchott. We stood by citizens when violations occurred, provided the government with serious consultations to improve human rights conditions, and issued reports that were sometimes strongly critical, especially in the areas of justice and freedoms.

This approach strengthened the commission’s credibility, culminating in achieving the highest international rating (“A”) from the Global Alliance of National Human Rights Institutions, election to the presidency of the Arab Network of National Institutions, and appointment as vice president of the Francophone Human Rights Commission.

Today, the priority for the commission is to continue on this path: to maintain independence while continuing its dual role as government advisor on one hand and independent monitoring and evaluation body on the other. This moderation has allowed the commission to be a trusted and credible actor in both the national and international human rights arenas.

After serving two consecutive terms, how do you describe the responsibilities of this position, and are you satisfied with that period overall?

Serving as head of the National Human Rights Commission carries enormous responsibilities. The commission is independent and in an advisory role to authorities, which is a trust that cannot be taken lightly. I endeavored to fulfill this duty faithfully. We acted on multiple levels according to the demands of our work and conscience. We approached all aspects of human rights, combated discrimination and slavery, supported those who fight them, and ensured open channels of communication with authorities at all times.

Our achievements, which are our duty, can be reviewed to see what was accomplished. Authorities recognized and commended these efforts at the end of our term, and we wished success to those who followed in this influential position.

How do you assess the state of human rights in Mauritania today?

Mauritania has made notable progress in recent years in the field of human rights, both in terms of legal texts and legislation, and through the establishment and strengthening of institutions tasked with protecting and promoting these rights. Significant efforts have been made, and human rights have become a political priority. However, protecting human rights requires constant, daily effort; there is no room for complacency.

Challenges remain, particularly in freedoms, where gaps exist in laws restricting free practices, dealing with peaceful demonstrations, and establishing associations and political parties. Nevertheless, the overall picture is encouraging, and we hope that this positive trajectory continues without regression, especially since Mauritania has recently improved its standing and gained positive recognition in the human rights field.

Whenever human rights in Mauritania are mentioned, the issue of slavery takes center stage. Why has it loomed so large in Mauritanian society, and how far has the country come in addressing it?

There is no taboo in discussing this issue in Mauritania, because slavery has existed across the world throughout different historical periods. Globally, there are about 40 million enslaved people, and even Europe used humans as machines to build economies, civilizations, and the foundations of life. Most stages of civilization included forms of slavery.

When the United States addressed slavery, it called it the “Shared Past,” a clear acknowledgment that slavery existed worldwideو

Mauritania now has an almost comprehensive legal framework to combat slavery and is working to enforce it consistently. Under the law, slavery is classified as a crime that never expires, carrying penalties of up to ten years in prison.

Slavery’s legacy is present in Mauritanian society, and it is not only the state that has addressed it; organizations and institutions have also acted to help eradicate it. Some human rights organizations were founded specifically for this purpose. The state faces the phenomenon, and society participates as well. Courts have issued rulings in slavery-related cases.

The existing laws are clear, but they must be applied strictly, without favoritism or interference. During my tenure as head of the National Human Rights Commission, our recommendation to all administrative and executive authorities was that there should be no obscuring of facts or yielding to any influence or pressure that violates the law.

It is important to note that the international community’s portrayal of slavery in Mauritania is inaccurate and exaggerated. There are no slave markets in Mauritania, and the international community should reconsider its overstated position. Unfortunately, there is malicious propaganda presented to the world regarding slavery in Mauritania.

The reality is that while cases of slavery and its remnants do persist, particularly in rural areas, they are not on the scale often portrayed. Claims that 20 percent of Mauritania’s population is enslaved are misleading. It is essential to place the issue in its proper context in order to find effective solutions.

Corruption remains a persistent concern in Mauritania, with many pointing to its varying levels across the state. How do you see this challenge, and what real solutions can address it?

It is natural for all governments to pledge to fight corruption, but the seriousness of addressing this issue varies over time. True national progress cannot be expected without firmly confronting corruption. The tools to combat it exist in Mauritania, and political will has been declared multiple times. What is needed now is to implement it concretely, closing the door on all abuses, applying strict measures, and establishing clear policies with steadfast determination to prioritize national interest and ensure equality among citizens.

‘For or Against’ in Mauritania

How do you see the current political trends in Mauritania, where everything seems reduced to being either for or against the authorities?

The political scene in Mauritania has become dominated by a binary logic: those who are with the authorities and those who are considered opponents. This simplistic classification is not only inaccurate but also dangerous. It undermines three core principles: objectivity, independence, and national interest. Today, it is impossible to analyze any government action without immediately placing its supporters in a predetermined category.

For example, if someone highlights security as a major achievement and thanks the authorities for ensuring a degree of safety in the current regional context, they are immediately accused of currying favor for personal gain. Yet security in a volatile environment is a vital achievement that deserves acknowledgment. Similarly, gradual improvements in civil registration systems represent essential progress in governance.

Mauritania’s growing presence on the international and diplomatic stage strengthens its image and attracts the attention of nations and investors. These are real accomplishments, and it is legitimate to recognize them. However, any public acknowledgment is often interpreted as blind loyalty.

Conversely, criticizing public policies immediately labels one as an “opponent.” In reality, pointing out systemic flaws is a patriotic duty. The education system struggles to prepare future generations, healthcare suffers repeated failures, administrative inefficiency persists, the judiciary faces challenges in delivering justice, and the private sector remains weak, discouraging investment and sustainable development. Highlighting these issues is not mere opposition, it is a call for reform aimed at improving governance.

Reducing national discourse to a “for or against” equation serves no one. This binary logic stifles thinking, prevents consensus, and ultimately harms the national interest. Mauritania deserves more than a forced choice between blind loyalty and absolute opposition. It deserves free, critical, and nationally minded analysis aimed at collective progress.

How do you see the amendment to the party law passed in early 2025?

The constitution is the highest guarantor of rights and freedoms, including freedom of association and the creation of political parties. Any restriction beyond what is necessary to protect public order or civil peace can undermine these rights. Conditions or limitations must be proportionate to the legitimate goal being pursued. If regulation becomes a tool for narrowing participation or exclusion, it weakens pluralism and limits political engagement. In democratic societies, freedom is the norm and restrictions are exceptions justified only by extreme necessity. The more this space is constrained, the less opportunity there is for peaceful power transitions and flourishing democratic life. Established political norms that ensure space for expression and participation are as important as the written law. Any reduction in this space may violate the spirit of democracy, even if legally justified.

Given your past role, how do you see the state of prisons in Mauritania?

I am no longer in a position to assess them formally, but during my tenure as head of the Human Rights Commission, I visited every prison and reported critical issues to the authorities, including severe overcrowding in some facilities. This is what I can share on the matter.