How German Efforts to Integrate Islam Into Education Turned Into a Battleground

“No studies have examined the effectiveness of Islam classes in preventing radicalization.”

Germany’s Association for Education and Training (VBE) has called for the introduction of comprehensive Islamic religious education in schools across the country, an unprecedented step aimed at promoting religious knowledge and fostering awareness of pluralism within the school community.

Despite the division between those who view Islam itself as part of German identity and those who insist it is limited to Muslims only, the debate itself reflected a fundamental shift in public debate, highlighting that issues of language and religion remain central to the integration process.

The teaching of Islam has remained at the heart of the political debate between advocates of integration and advocates of isolation, between those who see it as a means of promoting coexistence and those who fear it is a step toward legitimizing Islam within the German state.

The debate over Islamic education is not just reserved for Germany. As the Muslim population across Europe grows, both support for and opposition to Islamic teachings have risen in multiple European nations.

Islamic Education

“Islam is part of Germany.” This phrase was uttered by former German President Christian Wulff in October 2010 and repeated again in mid-2019, opening the door to endless debates and discussions on the role of Muslims in German society.

In this context, VBE Federal Chairman Gerhard Brand in comments to the Redaktions Netzwerk Deutschland (RND) recently called for the teaching of Islamic religion to be universalized in all educational institutions nationwide, similar to Catholic and Protestant Christian religious education.

This call has revived the debate about the place of Islam in the German public sphere and how it is reflected within the educational system.

He urged political leaders to ensure that schools are equipped with the necessary personnel and materials, and that programs are implemented quickly and expanded over time.

He pointed out that the reality of Islamic religious education in Germany remains uneven from one state to another.

Stefan Dull, president of the German Teachers’ Association, told the RND that “religious education in public schools, taught by teachers trained and state-certified in Germany, can provide a counterbalance to fundamentalist attitudes — mediated by the family or by fundamentalist preachers online.”

No studies have examined the effectiveness of Islam classes in preventing radicalisation, according to Harry Harun Behr, a professor of Islam studies and pedagogy at Frankfurt’s Goethe University.

However, he noted that the classes are valuable because they show students their faith is as important as others taught in their schools and because they show Islam as a religion that is open to reflection and self-criticism.

Advocates say that expanding access to these classes is essential for integration and for protecting students from extremist influences.

The Turkish Community in Germany also welcomed the initiative but warned of political and structural hurdles.

“Islamic religious education is a must — just like Catholic and Protestant religious education,” said the group’s chairman, Gokay Sofuoglu.

He called for educational standards to be aligned at a national level, while acknowledging the constitutional limits imposed by Germany’s federal system.

“We would need a nationwide Islamic cooperation partner. Unfortunately, that isn’t in sight at the moment,” he said.

Religious Equality

School religious education in Germany is based on Article 7 of the German Basic Law, which stipulates the right of all religions to teach their religion in schools.

In some German states, religious education is a core subject for students belonging to a particular religious denomination.

Students are automatically enrolled in religious classes without any registration, with the parents of students under the age of 14 or adults being given the freedom to decide whether to participate or withdraw from these classes.

The German constitution requires that education be consistent with the principles of religious communities, provided that the religious education remains Supervision is in the hands of the state, giving churches and religious organizations a stake in curriculum development and teacher selection, while the states are solely responsible for implementation.

This constitutional provision has provided an important reference for German Muslims to demand that their children receive Islamic religious education that is consistent with the principles and teachings of their religion.

This demand is also driven by Islam's status as the second-largest religion after Christianity in Germany.

According to estimates, around 5.5 million Muslims live in Germany, and at least 580,000 are attending school as of 2020.

Yet only around 81,000 students are currently enrolled in Islamic religious education programs.

This significant gap reflects a clear gap in equal opportunities and raises questions about the German education system's ability to integrate various religions into its official curricula, in line with the constitutional principles of religious freedom and equality.

Controversial Experiments

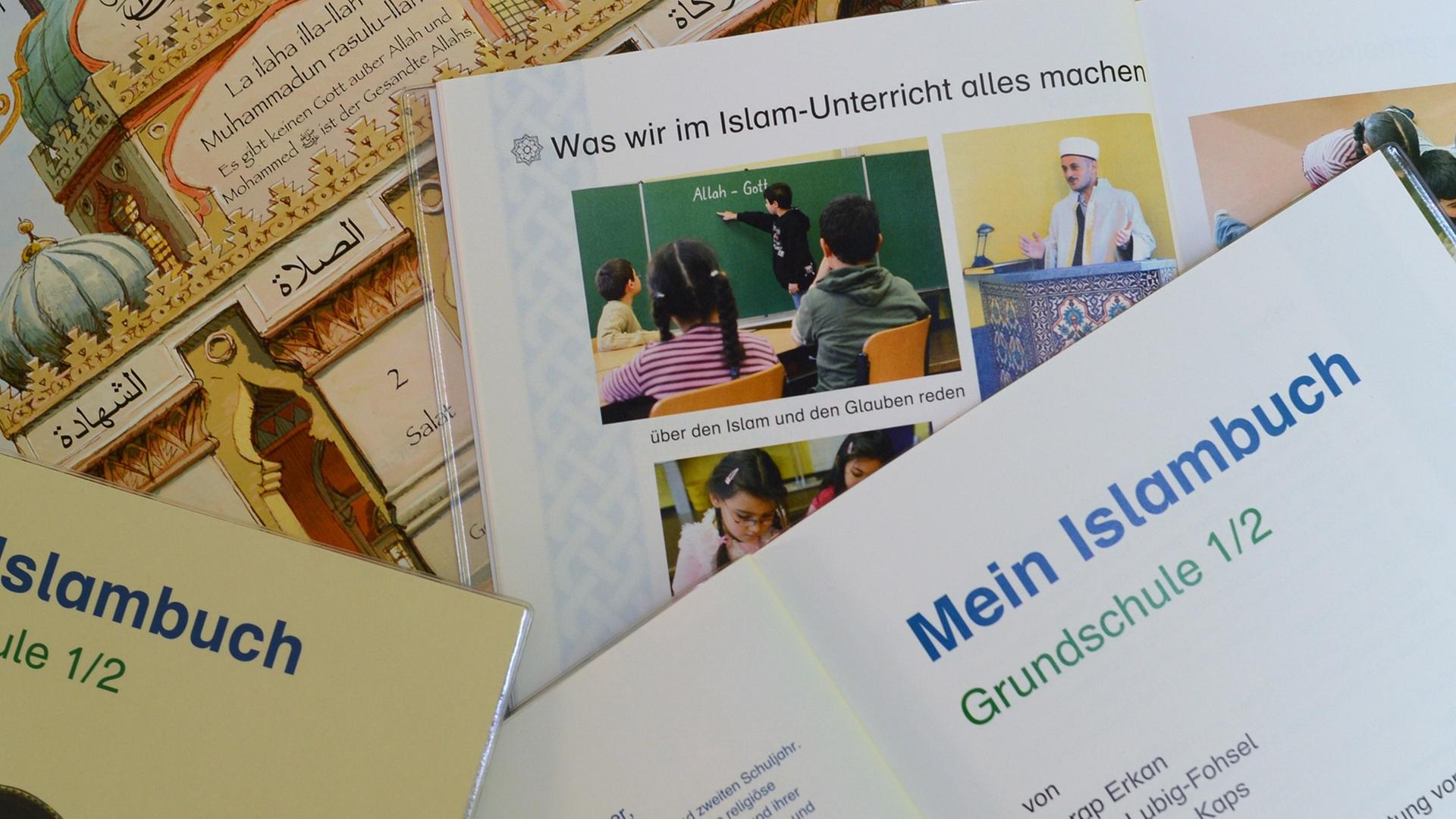

Germany began teaching Christianity in its schools decades ago, while the teaching of Islam remained a limited experiment among the states.

At the end of the last century, it was limited to the subject of religious instruction, which was taught in Turkish, and later in German, and under state supervision only.

With the recommendation of the German Islam Conference (DIK) at its third session in 2008 to introduce Islamic education, interest in teaching it increased, and pilot and systematic projects were launched under the name ‘Islamic Religious Education’.

The first pilot experiments began in North Rhine-Westphalia, the state with the largest Muslim population in the country.

In the late 1990s, the state launched pilot Islamic religious education classes in German and Turkish, before transforming them into an official state-recognized program in 2012.

However, the experiment faced political controversy surrounding the government advisory committee overseeing the curriculum, and in the absence of an official Islamic body representing Muslims, it proceeded hesitantly, alternating between progress and decline.

In Lower Saxony, the experiment followed a similar course since 2003, with Islamic education beginning in cooperation with local religious associations.

However, in 2017, an administrative court ruled that these associations were constitutionally ineligible for religious representation, disrupting the experiment and turning it into a fragile model that reveals the dilemma of formal recognition of Islam as an institutional religious component.

The state of Hesse witnessed one of the most controversial experiments, taking a different path by formally recognizing the Ahmadiyya community as a public religious body in 2013, granting it the legal right to teach Islam in public schools.

Although this step represented an important precedent, it was criticized for not representing the majority of Muslims.

The state of Rhineland-Palatinate initially limited itself to general classes on introducing Islam.

However, in 2024, it signed agreements with four Islamic groups in preparation for the official inclusion of Islamic education, sparking criticism from right-wing parties, which questioned these groups' loyalty to the German constitution and values.

Hamburg has adopted a unique model based on religious education for all, where religions are taught in shared classes to promote pluralism and coexistence.

But many Muslims considered this a circumvention of their demand for a separate educational subject, like Christians.

The experiences of other states show that the treatment of Islamic education in Germany is more diverse, with states that officially adopt Islamic education in partnership with local associations, such as Berlin, and others that implement pilot projects, such as Saarland.

States such as Bavaria and Schleswig-Holstein offer Islamic education without the participation of Muslim representatives, while eastern German states refuse to include Islamic education in their school curricula under any name.

Complex Challenges

The experiences of the states reflect a vacillating path between the pursuit of Islamic integration in education and the dilemmas facing its implementation on the ground.

Muslims in Germany still lack a central, legally recognized institution similar to the Christian churches, while recognition of Islamic organizations remains uneven among the states, raising constitutional debate over who is authorized to negotiate with the state regarding curricula, teachers, and other organizational aspects.

There are also legal and political challenges centered around religious pluralism and the principle of neutrality.

The German Constitution mandates respect for freedom of religion and the neutrality of the state, making it a delicate balance between promoting pluralism and preventing division while preserving the values of tolerance and equality.

Those responsible for designing Islamic curricula in Germany also face a significant challenge in developing balanced educational curricula that take into account religious and linguistic diversity, and that are neutral and avoid politicization or extremism.

This is compounded by social and ethnic divisions in Germany and rising hostility toward Muslims both inside and outside of schools.

Observers believe that the generalization of the Islamic religion curriculum in schools across all German states still has a long way to go, due to a number of intertwined factors.

They attribute this to the federal nature of the education system, as each state has its own educational mandate. This makes the issue dependent on political shifts within each state, in addition to exploiting this diversity in partisan and media debate.

Furthermore, the urgent need to train qualified teachers capable of teaching Islam in a manner consistent with German educational standards cannot be ignored.

Although there are teachers from Islamic backgrounds, training them according to the German educational system and ensuring their neutrality requires a study program that sometimes extends to five years, making bridging the gap even more difficult.

However, the main challenge also lies in the cost of implementing Islamic education in German schools on a large scale, as it requires significant funding for curriculum development and teachers training.

Even with the widespread support recently expressed by the VBE, political polarization makes the generalization of Islamic education a long-term project that requires clear legislation, stable agreements, and gradual funding.

Since the introduction of Islamic education in German schools, the issue has transformed from an educational issue into an arena of political conflict.

Some political parties view this measure as a threat to national identity and official recognition of a religion not rooted in German culture.

The political debate has taken on broader dimensions with the rise of the far-right and populist parties, who have exploited the issue of Islamic religious education to promote a narrative that argues that Islam does not belong in Germany and that its teaching in schools encourages isolation rather than integration.

In Bavaria, traditional parties, including the Social Democratic Party (SPD), the Greens, and the Christian Social Union (CSU), supported the inclusion of Islamic education as a tool for integration.

However, the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) filed objections, demanding the teaching of a unit on ethnic values instead of religious subjects, which they described as politicized. But the Constitutional Court rejected the request.

These parties have exploited every local experience to challenge the project to teach Islamic religion in the country's schools, both politically and legally, as occurred in Hesse and North Rhine-Westphalia last year, when the FDP demanded that Islamic education be replaced with mandatory ethics.