With the Outbreak of Cholera, An Investigation Reveals the Corruption of the WHO Office in Syria

It is not only pandemics that destroy the health situation in Syria, the accusations of corruption and collusion with the Assad regime and Russia, which have recently targeted the offices of the WHO in Damascus, seem to be more dangerous to the deteriorating health reality in the country, which is suffering from an outbreak of cholera after twelve years of war, famine, poverty, and destruction.

An investigation by the Associated Press revealed more than 100 documents with letters and other classified materials in an indictment case against the director of the WHO's offices in Syria, Dr. Akjemal Magtymova, who was involved in financial corruption for the benefit of the Assad regime.

Magtymova is a citizen of Turkmenistan. She previously held a number of positions, including the position of Agency Representative in Amman and Emergency Coordinator in Yemen. She assumed her position in Syria in May 2020, coinciding with the global outbreak of the Coronavirus.

It is noteworthy that WHO elected the Assad regime on May 28, 2021, as a member of its Executive Council, in a move that seeks to legitimize it, despite all the UN reports condemning him of deliberately targeting health facilities over the past decade.

Several Western media outlets had revealed, in earlier times, corruption in the work of the UN organizations in Syria and their continued submission to blackmail by officials of the Bashar al-Assad regime.

Today #Syria was elected as a new member of the @WHO Executive Board (EB) among other newly joining members for the period of 3 years. pic.twitter.com/DdwZEEZfNo

— WHO Syria (@WHOSyria) May 28, 2021

WHO Scandal

On October 21, 2022, WHO announced that its Office of Internal Oversight Services is investigating allegations of corruption against the director of its Office in Syria, Dr. Akjemal Magtymova, which sheds light again on the issues of corruption in the work of UN organizations operating there, and most of them are subject in one way or another to the conditions of the Assad regime and the blackmail of its security services.

WHO confirmed, in a statement, that the investigations are still ongoing and described them as long and complex, refusing to comment on Magtymova's violations, citing confidentiality and employee protection issues.

The organization had received complaints from dozens of employees, which sparked one of the largest internal investigations of the WHO in years.

Internal documents and emails also raised serious concerns about the use of WHO funds under Magtymova's leadership, as staff alleges she has misused limited donor funds intended to help more than 12 million Syrians living in dire conditions and in dire need of health assistance.

According to the documents, the budget of the WHO office in Syria last year amounted to about $115 million, and Western donor governments contribute about $2.5 billion annually; while the latest version of the Brussels Conference of International Donors, months ago, pledged more than $6 billion to support the future of Syria, during the current year and beyond.

However, the latest allegations about the director of the WHO's office in Syria raise questions about how the money was spent and whether the Syrians were actually let down.

The documents also show that Magtymova held a party to praise her own achievements at a cost of $11,000, at the expense of the WHO, at a time when the country was struggling to obtain vaccines for the Coronavirus, in addition to its previous failure to realize the seriousness of the pandemic in Syria and endangering the lives of millions.

Magtymova also used WHO funds to purchase good quality laptop computers and expensive cars for the Assad government's Ministry of Health, in addition to holding secret meetings with the Russian army, in violation of the impartiality of the WHO as a UN organization.

In May 2022, the WHO Regional Director for the Eastern Mediterranean issued a decision appointing a charge d'affaires in Syria to replace Magtymova after she was relieved of her position, but she still receives a salary at the level of a director.

On his part, Dr. Radwan Ziadeh, senior fellow at the Arab Center in Washington, D.C., said in a statement to Al-Estiklal: "This is not the first time that a corruption issue has been raised at the WHO in Syria."

He added, "There were many reports by the British press about the corruption of the WHO, but unfortunately the UN did not conduct any meaningful investigations in this regard."

Dr. Ziadeh pointed out that "the Assad regime's benefit from the WHO has become widely documented," calling for a radical change within the structure of the UN.

As for journalist Suhail al-Ghazi, he said in a statement to Al-Estiklal: "We are accustomed to the weak performance of the UN organizations inside Syria, but this scandal is bigger than the above because it exposes the corruption of the director and the misuse of her position, in addition, these practices coincided with the Covid-19 pandemic, without any concern by the UN for investigation and accountability."

Corruption and Collusion

The Associated Press reported, in an exclusive report on October 20, 2022, that it had obtained more than 100 confidential documents stating that WHO officials had told investigators that the organization's representative in Syria had been involved in several corruption operations.

The documents also indicate that Magtymova has constantly pressured WHO staff to sign contracts with senior politicians in the Assad regime, thus undermining the organization's and donor funds' spending mechanism.

In a document sent to the WHO director-general, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, in May 2022, a Syria-based employee said that "Magtymova has hired incompetent relatives of officials from the Assad regime, including some accused of human rights violations."

According to the documents, Magtymova, like many other UN employees in Syria, has been staying for two years at the Four Seasons Hotel in Damascus in a spacious multi-room suite that costs $450 a night.

Among the other issues that Magtymova is facing are the discrepancies in a health project in northern Syria between what the organization paid and what equipment was found.

Several employees also confirmed that Magtymova was involved in several questionable contracts, including a transfer deal that awarded several million dollars to a supplier with whom she had personal relationships.

Other employees also reported that they were pressured to cut deals with senior officials of the Assad regime for essential supplies, such as fuel, at inflated prices.

Meanwhile, another employee close to Magtymova received $20,000 in cash to buy medicine, despite the lack of any request from the Assad government's Ministry of Health.

It is noteworthy that the UN had been widely criticized in 2016 due to the appointment of Shukria Mekdad, the wife of the current regime's Minister of Foreign Affairs, Faisal Mekdad, among the cadres of the WHO when her husband was Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs, note that he was the one who negotiated with the UN representative to approve the annual humanitarian response plan in Syria.

The WHO had also funded a health center on the Lebanese border to treat the wounded of the Hezbollah militia before transferring them to Lebanon.

In addition, the organization also financed the Assad government's Ministry of Defense with more than $5 million through the blood bank, which in Syria belongs to the Ministry of Defense and not to the Ministry of Health.

Big Thefts

The Assad regime has a long history of corrupting and politicizing UN agencies and has repeatedly used these agencies and their funding to bypass the sanctions imposed by Western countries on several Syrian companies and personalities close to it.

In turn, the Middle East Eye website reported last July that millions of dollars in UN procurement costs in Syria go indirectly to companies close to the Assad regime.

For example, Maher al-Assad, the brother of the head of the regime, benefited from international procurement contracts to remove minerals in areas seized by the regime from the opposition and to recycle them for sale in the Hadeed metal manufacturing company owned by his close businessman, Muhammad Hamsho.

The UN agencies have also spent at the Four Seasons Hotel in Damascus, of which a third of the Syrian Ministry of Tourism has owned more than $80 million since 2014, in addition to dozens of contracts to fund organizations that cover the provision of humanitarian aid, such as the Syrian Trust for Development headed by Asma al-Assad.

The data also indicates that UN agencies purchased goods and services during the year 2020 with a value of more than $240 million, while 17 UN agencies purchased last year with a value of less than $200 million.

International reports have indicated that the Assad regime has worked over the past years to withdraw millions of dollars in foreign aid by forcing UN agencies to transfer aid funds to the Syrian pound at the lowest official price, which caused the loss of half of the foreign aid funds for the Syrian people, according to a report issued in October 2021 by the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

The report pointed out that the Assad regime has always directed international aid to areas it considers loyal to it, impeding its access to opposition-controlled areas and diverting food baskets to its military units.

On the motives of the UN agencies contracting with companies and organizations that are considered a front for the Syrian regime, journalist Suhail al-Ghazi explained in a statement to Al-Estiklal that "the policy of the UN, which can be described as negative neutrality, and a lack of understanding of the Syrian context, in addition to the fact that the concerned officials in the UN are indifferent to the verification of their contracts."

"For these reasons, agencies are withholding the names of their main suppliers under the pretext of protecting them, which contradicts the principles of transparency that international organizations must work with. This cover-up also contributes to a decline in the confidence of the press, human rights organizations, and Syrian citizens in these organizations," he added.

Mr. al-Ghazi demanded that there be a new mechanism to prevent the Assad regime from delivering aid to the Syrians, for example: finding a mechanism for distributing aid parallel to the UN mechanism and enacting laws that require organizations to have more transparency regarding procurement and beneficiaries within the regime's areas of control.

Cholera Outbreak

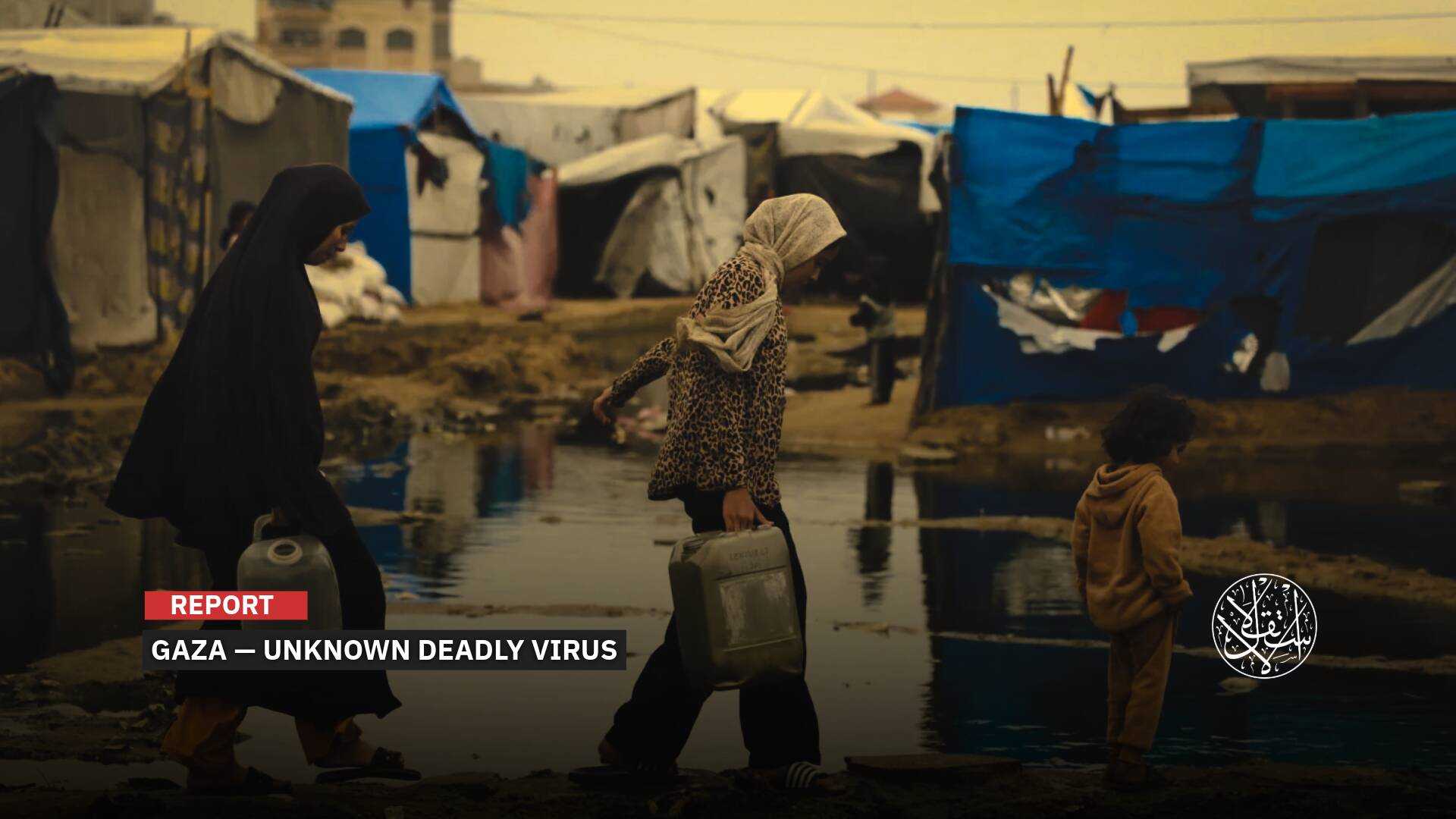

Since September 10, Syria has witnessed an outbreak of cholera in several governorates for the first time since 2009.

Cholera usually appears in residential areas that suffer from scarcity of drinking water or lack of sewage systems.

On October 19, 2022, the spokesman for the Secretary-General of the UN, Stephane Dujarric, revealed that the number of deaths from cholera in Syria had reached 68, indicating that the numbers are increasing.

In his press conference, Dujarric said, "There are 807 confirmed cases of cholera across the country."

According to the UN, cholera has spread in most parts of Syria, affecting 13 out of 14 governorates in the country, adding that limited testing capabilities and a largely dysfunctional health system made it difficult to ascertain the number of cases.

According to the WHO, the number of suspected cholera cases in Syria has reached about 16,000.

Over the past days, the WHO has temporarily suspended the standard two-dose cholera vaccination regimen to be replaced by a single dose due to vaccine shortages and the increasing outbreak of the disease worldwide.

Sources

- WHO Syria boss accused of corruption, fraud, abuse, AP finds

- This Is How UN Agencies Funded Entities That Committed War Crimes in Syria With Millions of Dollars

- Syria fights against cholera

- UN pays tens of millions to Assad regime under Syria aid programme

- Syria war: Millions in UN procurement costs go to companies close to Assad

- WHO rewards the Syrian regime for its atrocities

- How the Assad Regime Systematically Diverts Tens of Millions in Aid