Sudan And The Red Sea: Tracing Saudi-UAE Rivalries Amid U.S. Strategic Calculations

Abu Dhabi remains a key player in the Horn of Africa, despite Washington’s threat of sanctions.

Along the hidden fault lines stretching between Darfur, the Red Sea, and the Gulf of Aden, regional and international interests intersect in ways that shape Sudan’s war as much as they ignite it on the ground.

While Washington publicly condemns the atrocities committed by the rebel Rapid Support Forces militia in el Fashir and calls for a halt to the flow of arms to them, it quietly relies on Emirati military facilities in the Horn of Africa to launch operations against the Islamic State in Somalia.

This fundamental contradiction, revealed in an investigation by the British outlet Middle East Eye on November 26, 2025, draws on intelligence and diplomatic sources that converge with on-the-ground testimonies, raising profound questions about the nature of American “gray zone” operations and how bases in the UAE are being used, some of which are accused of supporting the very force Washington says it seeks to restrain.

Rubio’s Signal

U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio did not explicitly name the UAE when he emerged from a G7 foreign ministers’ meeting near Niagara Falls on November 13, 2025.

He merely said that Washington “knows which parties are supplying weapons to the Rapid Support Forces, and that support must stop.”

But when a journalist confronted him with a direct question, “But the UAE is supplying them with drones, Chinese drones,” Rubio did not deny it. He resorted to careful diplomatic language, saying he did not want to name any party at a press conference, “because the goal is to reach a good outcome.”

Between the lines, the message was clear: Washington knows, but it does not want a direct confrontation with a strategic ally such as Abu Dhabi.

Behind the scenes, the picture appeared even clearer. Sources in Washington told Middle East Eye that the U.S. State Department was considering a new package of sanctions targeting key figures linking the Rapid Support Forces militia, recently accused of widespread atrocities in el Fashir, to the UAE, which had been the primary sponsor of these forces for years.

El Fashir, the capital of North Darfur, has in recent weeks become a symbol of the war’s brutality, with reports of mass rape, killings, looting, and abductions, alongside satellite images showing pools of congealed blood in the streets.

Around the city, some 650,000 civilians and more than 300 foreign aid workers inhabit a stretch of land west of el Fashir.

International observers say they all face imminent danger, with Rapid Support Forces militia checkpoints set up just twenty kilometers from the area.

These atrocities have refocused both popular and political attention on the UAE’s role in the Sudanese war.

While Abu Dhabi continues to deny arming the Rapid Support Forces militia, mounting field, digital, and human evidence suggests otherwise: satellite imagery, serial numbers of weapons, flight-tracking data, and testimony from inside and outside Sudan.

Yet this evidence is highly sensitive, implicating a close ally of the United States, Britain, and “Israel,” as well as a key financial and military actor in the region.

At this fraught moment, an additional factor complicated the scene: direct pressure from Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman on President Donald Trump.

Reuters reported this on November 18, 2025, before Trump later announced that the United States would begin addressing the Sudan file.

At this point, the issue was no longer a bilateral dispute between Washington and Abu Dhabi, but an open struggle for influence between Saudi Arabia and the UAE over the future of Sudan and the Red Sea, which Washington has tried to manage cautiously without alienating either side.

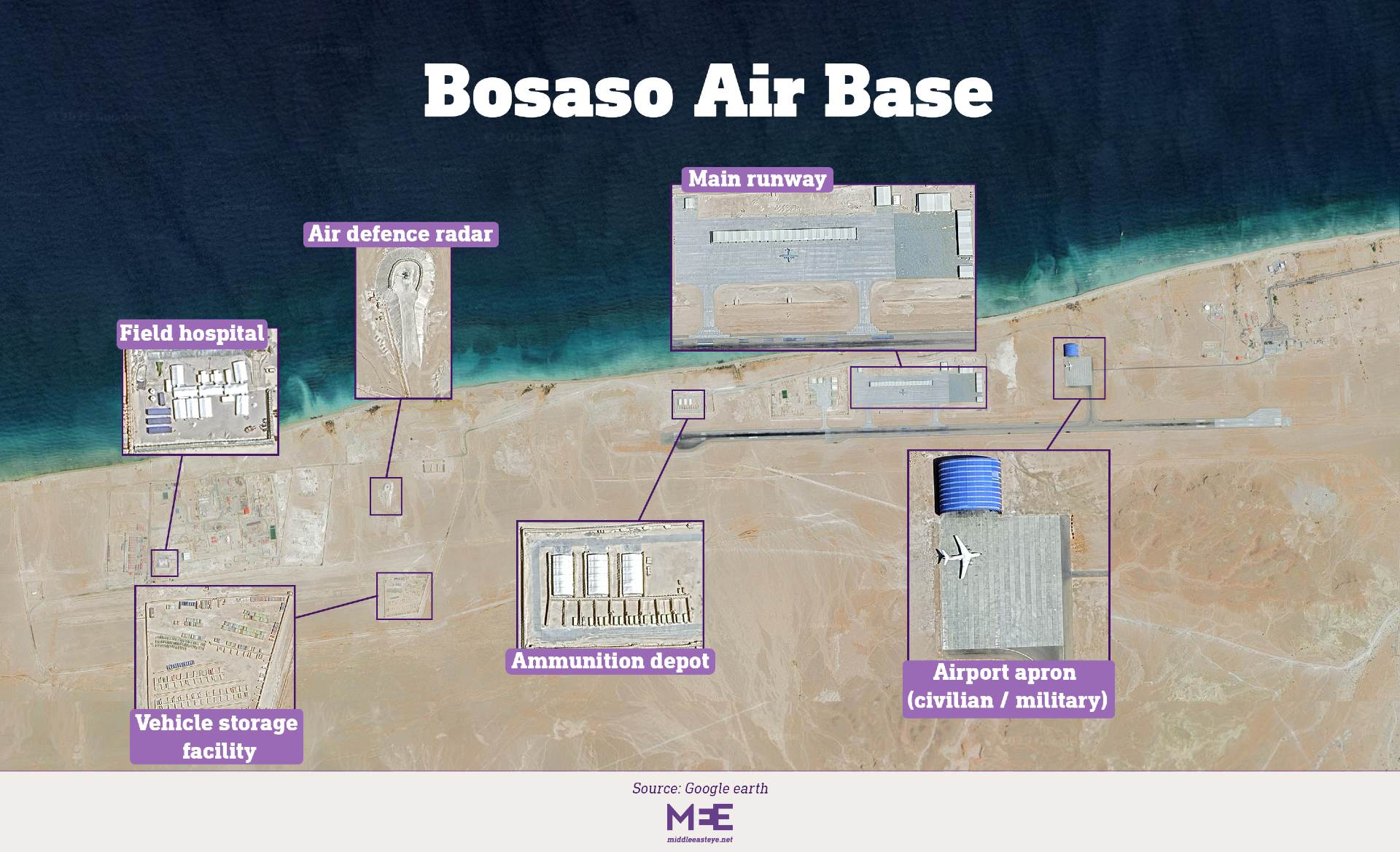

At the heart of this geopolitical paradox stands the coastal city of Bosaso in the semi-autonomous Puntland region of Somalia.

Overlooking one of the world’s most important maritime corridors, stretching from the Suez Canal through the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden to the Indian Ocean, Bosaso appears at first glance to be a quiet trading town.

A traveler once described it as resembling a small Mediterranean city, with charming buildings and boats scattered across the water.

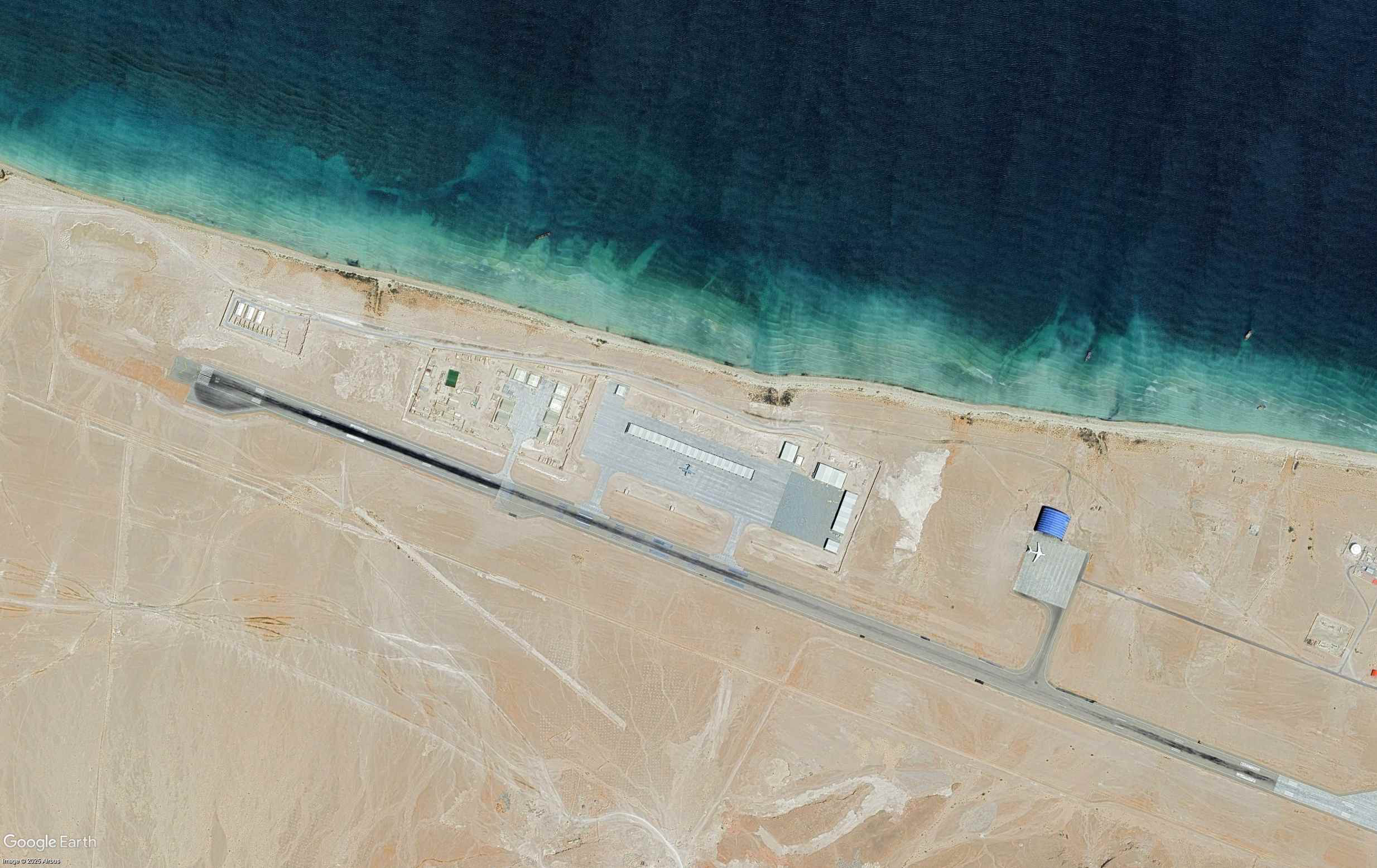

But over the past two years, Bosaso has witnessed a very different scene: massive cargo planes landing regularly at its runway, under the watch of local security forces and foreign advisers.

This airport, alongside the port, was developed with Emirati funding and oversight in recent years, before the Americans began using it as a launchpad for counterterrorism operations against Islamic State fighters who had reached Somalia from Syria and other parts of the Middle East.

U.S. sources familiar with these operations, as well as Puntland officials, confirm that the UAE used Bosaso as a hub to supply the Rapid Support Forces militia in Sudan, even as the United States relied on it to strike targets inside Somalia.

Just three days before Rubio condemned the Rapid Support Forces militia’s crimes in el Fashir and called for a halt to their arms supplies, U.S. Africa Command (AFRICOM) carried out an airstrike against Islamic State targets near Gulgul Cave, 32 kilometers southeast of Bosaso.

Since Trump took office in early 2025, Washington’s war against armed groups in Somalia has escalated sharply. His administration carried out 99 strikes this year, compared with 51 under Biden, according to the New America research center.

Some strikes were launched from naval vessels, but a significant portion was part of a broader operational network, overlapping official U.S. bases, such as Camp Lemonnier in Djibouti, with Emirati facilities in Bosaso and Berbera on the Somaliland coast.

Washington’s Calculations

Flight-tracking data analysis reveals some threads of this complex network. On July 29, 2025, a U.S. Marine Corps KC-130J transport aircraft, tail number 170283, flew from Camp Lemonnier in Djibouti to Bosaso, then continued to Mombasa before returning to Djibouti.

Camp Lemonnier, the largest U.S. military base in Africa, is now buzzing with a multinational presence, from China to France, prompting Washington to diversify its options and rely on alternative facilities in the Horn of Africa and along the Red Sea, foremost among them Bosaso and Berbera.

This backdrop explains part of the United States’ complicated calculus toward the UAE. As Sudanese analyst Kholood Khair, director of Confluence Advisory, points out, the U.S. finds itself forced to act as an arbiter between Saudi Arabia and the UAE, a role it has never been compelled to play in this way before.

The Trump administration is deeply engaged with both sides. It has political and security interests tied to “Israel” with the UAE, along with investment deals involving the Trump family itself, from Gaza reconstruction projects to artificial intelligence ventures.

At the same time, it maintains long-standing economic and financial ties with Saudi Arabia, alongside a potentially pivotal Saudi role in funding any settlement or reconstruction in Gaza and Sudan.

Former U.S. State Department official and ex-CIA analyst Cameron Hudson summarizes the paradox:

“The UAE has offered the use of Bosaso as a staging area when US forces are going into Puntland or Somaliland,” Cameron Hudson, a former State Department official and CIA analyst, told MEE. “It is not a permanent operation, but my understanding is that it has been made available and we have made use of it.”

Yet he adds that this alliance creates massive complications when Washington turns to Sudan. How can it pressure the UAE in Khartoum while simultaneously relying on its facilities in Puntland, Somaliland, and Yemen to pursue Islamic State, al-Qaeda, and Houthi targets?

To answer that question, one must look at the network of bases the UAE has woven around the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden in recent years.

Satellite imagery analysis by Middle East Eye shows military and intelligence activity on the islands of Abd al-Kuri and Samhah, part of the Socotra archipelago now under the control of the UAE-backed Southern Transitional Council, along with similar activity in the Yemeni coastal city of al Mokha and on the volcanic island of Mayon in the Bab el-Mandeb Strait, through which around 30 percent of global oil supplies pass.

On the African side, this network stretches from Bosaso and Berbera to facilities inside Sudan itself.

Air Bridge

Between March 2024 and August 2025, flight-tracking data revealed 77 landings in Bosaso, indicating that the city had become a permanent part of the UAE’s air bridge to Sudan.

During this period, two IL-76 transport aircraft, bearing the numbers EX-76015 and EX-76019 and operated by New Way Cargo Airlines registered in Kyrgyzstan, appeared repeatedly.

The planes landed dozens of times in Bosaso, coming from the Emirate of Ras al Khaimah or al Dhafra Air Base in the UAE. On some flights, the aircraft masked parts of their flight path, a pattern suggesting deliberate concealment, a behavior repeated in UAE-linked transport operations in Yemen, Libya, and Sudan.

A senior officer in Puntland’s marine police, stationed at Bosaso airport, described the movement of heavy logistical cargo to and from the IL-76s. He spoke of frequent flights, with shipments transferred to other aircraft bound for the Rapid Support Forces militia across neighboring countries, accompanied by tight security and the presence of Colombian mercenaries in Bosaso.

At the same time, data from sources such as FlightRadar24 showed direct flights of EX-76015 between Abu Dhabi and Ethiopia in September 2024 and February 2025.

Other flights were recorded between Bosaso and Aqaba port in Jordan, as well as flights by Gelix Airlines and Sapsan Airlines from Bosaso to Kufra and Benghazi in Libya.

It is worth noting that Libyan military militia commander Khalifa Haftar, a UAE ally in Libya, is reported to have deployed mercenaries who fought alongside the Rapid Support Forces militia in the desert triangle along the Libya-Egypt-Sudan border.

Al Mabrouka 2

Along the maritime frontier, shipping data between August 2023 and August 2024 tracked a UAE-flagged vessel named Al Mabrouka 2, flying the flag of Saint Kitts and Nevis, moving from Emirati ports toward the Gulf of Aden.

The ship stopped at the islands of Abd al-Kuri and Socotra before continuing on to Bosaso.

The vessel’s visits coincided with Emirati efforts to bolster infrastructure in the city. Other ships, including Takreem and YM 1, were recorded moving between UAE ports and Yemeni island bases along the Gulf of Aden and the Red Sea, in what appears to be a maritime counterpart to the air bridge.

This dual air and sea activity is linked to a direct Emirati presence inside Sudan itself.

According to investigative sources, the UAE maintains two military bases in Sudan: one in Nyala, South Darfur, and another in the al-Malih area, roughly 200 kilometers from el Fashir.

Together with the air and sea bridges, these bases form an interconnected network of runways, hangars, intelligence facilities, and ammunition depots, suggesting the existence of single regional operations hub run by Abu Dhabi, linking the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden to the heart of Darfur.

Saudi-Emirate Rivalry

But this strategic backdrop of Emirati deployment in the region cannot be separated from the Saudi-UAE rivalry.

Sudan, with its 750-kilometer coastline along the Red Sea opposite the Saudi coast, its vast agricultural resources, and gold, nearly 90 percent of whose official exports head to the UAE, represents an ideal arena for an Emirati expansion project.

This project, as Amgad Fareid Eltayeb, director of the Sudanese Public Policy Center Fikra, explains, is based on creating zones of instability and then seizing control of the ports, echoing an old British imperial model.

Eltayeb adds that the project does not align with Saudi Arabia’s long-term post-oil strategy, which focuses on Red Sea stability and its exploitation as an economic and security backbone for Vision 2030.

From Washington’s perspective, the picture is even more complex.

Jalel Harchaoui, an analyst specializing in North Africa and political economy, notes that Trump historically admired and sympathized more with Saudi Arabia, and that Washington’s tolerance of UAE actions is a recent phenomenon compared with its long-standing relationship with Riyadh.

Some voices in the U.S. capital now even view the UAE as a brash startup, reminiscent of “Israel” in its style of regional behavior.

By contrast, Saudi Arabia’s position as a potential key financier for reconstruction in Gaza and Sudan, and as a gatekeeper for any major Middle East deal, adds weight to its role in the calculations of the U.S. administration.

Decisive Factor

Amid all this complexity, U.S. President Donald Trump emerges once again as a decisive factor. On his platform, Truth Social, he wrote that enormous atrocities are being committed in Sudan, and that his country would work with Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Egypt, and other partners to end these violations and restore stability.

Yet while these words were being broadcast to the world, another IL-76 aircraft was approaching Bosaso’s runway, landing with a roar, its engines echoing across a city that has become a logistical hub in a multi-pronged project.

In a world shaped by powerful figures such as Trump, Mohammed bin Salman, and Mohammed bin Zayed, major decisions often resemble deals struck between elites rather than policies emerging from stable institutions.

The UAE is not a bureaucratic state where policies are debated over long periods; it is a centralized system that makes decisions quickly and moves through a network of partners and intermediaries.

Washington itself, particularly under Trump, tends to strike deals similarly, outside the traditional frameworks of foreign policy-making.

This paradox is evident in Bosaso: on one hand, the United States wants to appear tough on Sudan, waving the threat of sanctions, condemning the crimes of the Rapid Support Forces militia, and pledging to work with Riyadh, Cairo, and Abu Dhabi to end the atrocities.

On the other hand, it relies on a UAE-developed base on the ground, along with a network of bases, ships, and aircraft connected to Abu Dhabi, to run operations in Somalia, monitor the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden, and track the Houthis, Islamic State, and al-Qaeda.

In this context, former U.S. State Department official Cameron Hudson poses a fundamental question:

How can anyone distinguish between equipment going to the Rapid Support Forces militia and that used in counterterrorism operations when there are warehouses full of deadly material?

For him, this is Emirati ingenuity; it provides the perfect cover, blending white and black operations into a continuous stream of gray operations.

At the same time, Abu Dhabi remains an indispensable player in the battles of the Horn of Africa and the Red Sea, no matter how loudly condemnation is voiced or how heavily Washington threatens with sanctions.

Sources

- Sudan And The Red Sea: Tracing Saudi-UAE Rivalries Amid U.S. Strategic Calculations

- UAE bases arming the Rapid Support Forces fund U.S. “grey operations” in Somalia [Arabic]

- A 33-year history of U.S. military interventions in Somalia [Arabic]

- How UAE bases arming Sudan's RSF support U.S. ‘grey ops’ in Somalia