Holding Regime Figures to Account: Between Deals and Trials, Where Is Justice in Syria Headed?

Transitional justice is not a slogan but a prerequisite for rebuilding trust between the state and society.

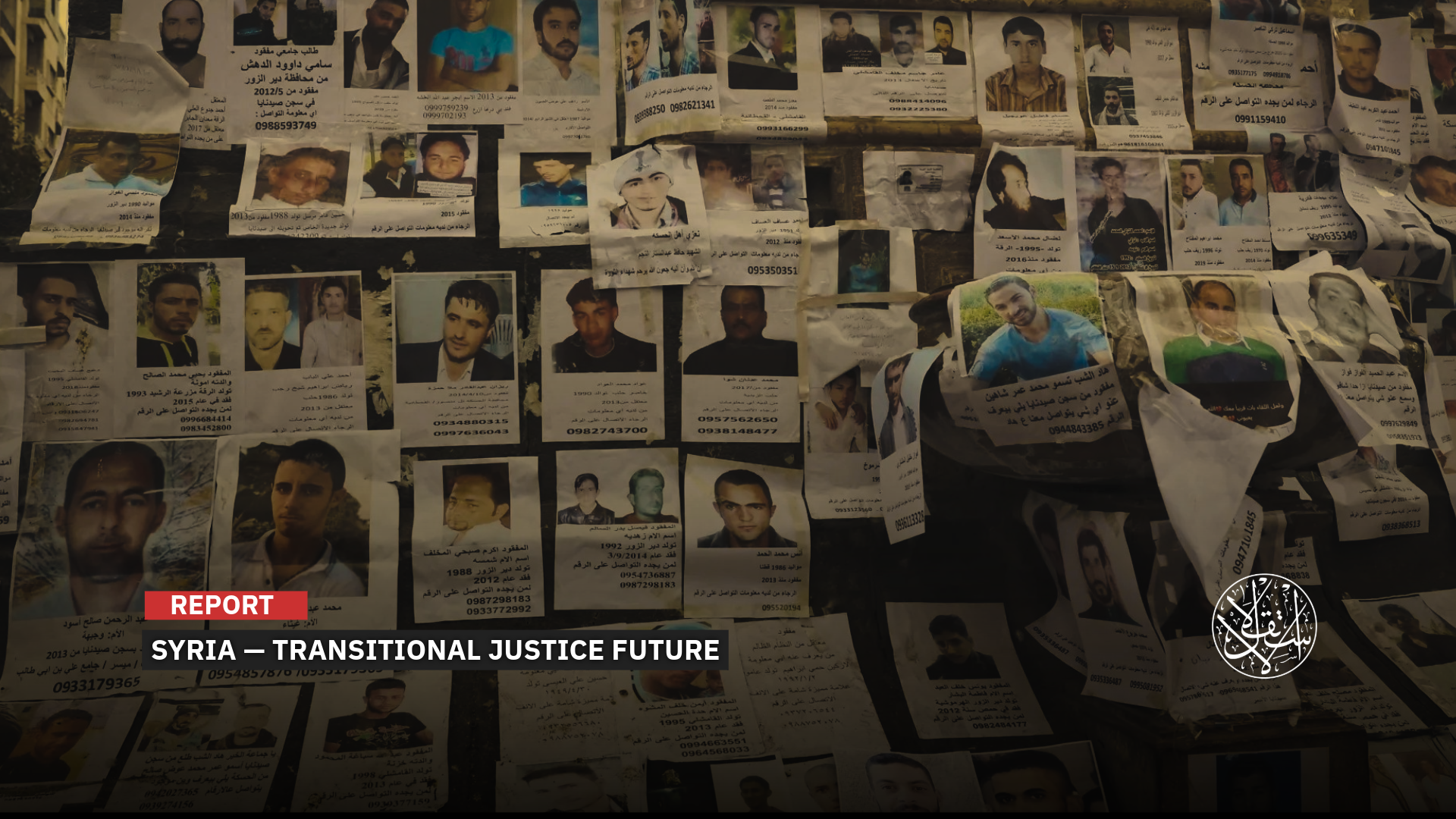

The Syrian street is steadily turning up the pressure on the country’s new leadership to lock in the principles of transitional justice and hold those responsible for crimes against civilians to account after years of Bashar al-Assad’s rule. The push has only intensified after so-called security settlements were struck with figures whose names are tied to some of the regime’s most notorious repression and abuses.

The result has been a growing wave of public anger across Syria, driven by what many see as a soft approach toward war criminals from the revolution years. For a wide segment of Syrians, the message has been jarring. Some of those responsible for grave violations still appear to be beyond the reach of the law, even as calls grow louder for real justice that can restore trust in the country’s next phase.

Security Settlements

In recent months, the Syrian government has moved to strike security settlements with figures known as some of the former regime’s most influential economic backers under Bashar al-Assad. The authorities have also released several militia leaders just months after their arrest, without clear trials, despite accusations that they continued to bankroll the war machine until the final days before Assad fled to Russia.

These moves have raised sharp questions about the new leadership’s commitment to transitional justice. For victims of past abuses and human rights groups, the fear is that the process could devolve into a hollow framework that falls short of delivering real accountability.

Many Syrians had pinned their hopes on fair trials for those responsible for crimes committed during the years of the revolution. Instead, some government steps have appeared more symbolic than substantive, offering little reassurance to those seeking redress and failing to confront the roots of the crisis.

With no public and transparent trials in sight, the justice Syrians have waited on for so long appears to remain trapped in a complicated path shaped by political and security calculations.

Syrian activists have criticized what they describe as an official reluctance to pursue those implicated in crimes against civilians, calling for civil society groups and victims’ associations to be involved in monitoring the judicial process. They stress that transitional justice is not a slogan but a prerequisite for rebuilding trust between the state and society and laying the groundwork for lasting national reconciliation.

Families of the missing and former detainees have also voiced frustration over the lack of concrete steps to uncover the fate of their loved ones. Many argue that the release of some accused figures sends a damaging signal and risks turning any future trials into something resembling victor’s justice.

As public anger has mounted, the eastern province of Deir ez-Zor has seen a series of high-level meetings since February 6, 2026, including separate gatherings at the Free People of Deir ez-Zor guesthouse and the provincial headquarters. The talks brought together the governor and senior internal security officials to address rising tensions sparked by settlements with militia leaders linked to the former regime.

The meetings followed settlements involving several commanders, including Firas al-Jaham and Madloul al-Aziz, in what officials described as an effort to contain public outrage and explain the measures taken to maintain security.

Participants discussed security and social concerns and presented proposals, while officials pledged to continue the dialogue in support of civil peace and regional stability.

Raed al-Melhem, an activist who attended the meetings, told Syria TV that a senior security official said the recent settlements were part of a broader state policy and were also shaped by external pressures tied to managing internal conditions. He noted that the measures included former militia leaders from Deir ez-Zor.

Madloul al-Aziz remains a particularly controversial figure. He served as a member of parliament from 2020 to 2024 and has been accused of leveraging his influence and ties to powerful figures and foreign-backed militias, including Nawaf al-Bashir, who also reached a settlement with the state despite previously leading the Lions of the Tribes militia linked to Iran’s Revolutionary Guard.

Firas Dhiab al-Jaham, widely known as Firas al-Iraqiya, served as the commander of the National Defense Forces militia in Deir ez-Zor. Since the early days of the 2011 revolution, he has been closely linked to the security services and was known for his role in crackdowns and the arrest of protesters.

Opposition outlets and local networks accuse him of responsibility for serious abuses and targeted killings against regime opponents in the city. His inclusion in the latest round of settlements has become a flashpoint, further intensifying the debate over the future of transitional justice in Syria.

Transitional Justice

On the economic front, several businessmen closely tied to Bashar al-Assad’s former regime have secured security settlements, most notably Syrian tycoon Muhammad Hamsho, long known for his close ties to the centers of power before the regime’s collapse.

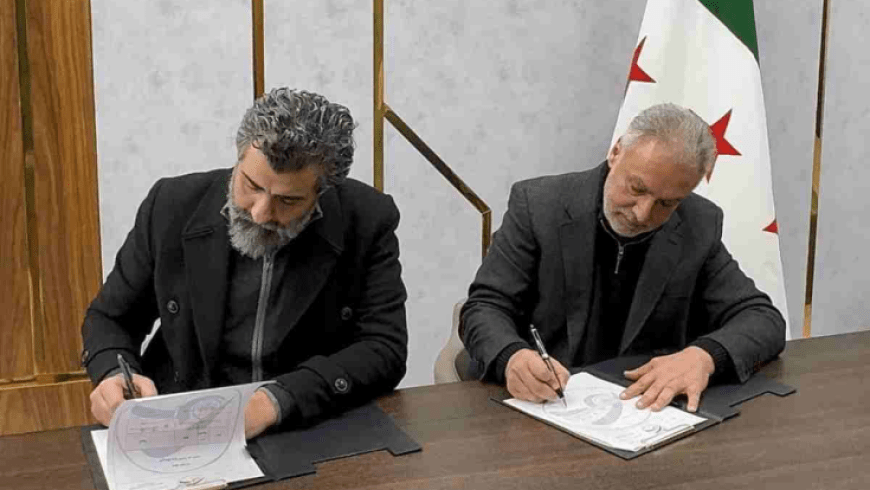

On January 7, 2026, Syria’s National Commission for Combating Illicit Gains (NCCIG) announced that it had finalized a formal settlement with Hamsho under a voluntary disclosure program aimed at promoting economic justice and improving transparency over the assets and holdings of businessmen suspected of benefiting from their proximity to the former regime.

But Hamsho’s statement following the announcement triggered a wave of criticism, with many arguing that the settlement was reached without a proper review of his role in supporting the former regime or holding him accountable.

Observers say settlements with figures who played military or economic roles in entrenching the former regime represent one of the most serious challenges facing Syria’s transitional justice process. These individuals were not merely economic beneficiaries but integral parts of the financial and political architecture that sustained the regime throughout the war.

International records show that the U.S. Treasury Department was among the first to sanction Hamsho, placing him on its sanctions list as early as August 2011. The designation cited information indicating that he provided direct support to al-Assad and his brother Maher al-Assad and served as an economic front for Maher’s influence across multiple sectors of the Syrian economy.

A similar backlash followed the government’s decision in June 2025 to grant a security settlement to Fadi Saqr, a former commander in the “National Defense Forces (NDF).” The move sparked widespread public anger, particularly after activists branded him the Butcher of Syria, accusing militias under his command of involvement in massacres against civilians, including the Tadamon massacre in 2013.

Controversy has also intensified over the lack of accountability for Farhan al-Marsoumi following the regime’s fall, despite accusations linking him to drug trafficking and to influence networks backed by regional actors.

His public appearances at official events, including the “Aleppo the Best for All” campaign in December 2025, as well as a 300,000 dollar donation to support public service projects, shocked many Syrians who saw the moves as further evidence of the absence of meaningful accountability.

Amid growing tensions, Syrian President Ahmed al-Sharaa announced on May 17, 2025, the formation of an independent body known as the National Commission for Transitional Justice (NCTJ). The body is tasked with uncovering the truth about grave violations committed by the former regime, holding those responsible to account, compensating victims, and entrenching guarantees of non-recurrence in support of national reconciliation. According to the official announcement, the NCTJ enjoys financial and administrative independence and has the authority to operate across all Syrian territory.

In a February 2, 2026 interview, with the Syrian News Channel, Justice Minister Mazhar al-Wais said transitional justice had become a central pillar of the post-regime phase. He stressed that the goal was to move Syria from an era of violations toward truth-telling, victim redress, accountability, and reparations.

Al-Wais said the Justice Ministry and Interior Ministry were working in coordination to pursue those responsible for abuses, noting that prosecutors had already begun moving forward on several cases. He added that the ministry had published information through its official platforms to promote transparency and reassure the public that the process was not merely symbolic.

At the same time, he acknowledged that the scale and accumulation of violations over more than fifteen years, some dating back to the 1970s and 1980s, make transitional justice a long and complex undertaking that requires time to build solid case files capable of delivering professional and lawful accountability.

Back to Power

Legal experts warn that rehabilitating figures from the former regime without clear accountability or acknowledgment of past abuses does not help build a new Syrian state. On the contrary, it could threaten social stability and deepen public anger, especially among families of the martyred and detained, many of whom still do not know the fate of their loved ones.

With Syria’s transitional justice law still delayed, human rights advocates argue that the government’s current measures, while significant, are not a lasting solution. At best, they may serve as temporary tools to prevent some perpetrators from evading justice until a fully structured judicial process is launched.

“The steps currently available to speed up accountability will not deliver structural solutions before the transitional justice law is issued,” Ahmed Koraby, deputy head of the Syrian Dialogue Center, told Al-Estiklal.

“But it could function as emergency or precautionary measures while the legal framework is set.”

“The first step involves judicial detention procedures. Syria’s current judicial authority law allows courts to detain suspects, hold them in custody, and extend arrest warrants, as has already been applied to prominent figures from the former regime,” he added.

“The aim is to fast-track accountability rather than rely just on legal settlements.”

The second step, Koraby said, involves travel bans to prevent accused figures from leaving the country before investigations are complete. Courts can also impose precautionary freezes on assets to stop funds from being moved or used to circumvent justice.

Even so, Koraby stressed that these measures remain incomplete without the launch of actual trials. The absence of clear and public prosecutions lies at the heart of the crisis.

He also highlighted the need for greater transparency, including public disclosure of the estimated number of suspects, which official figures put between four and five thousand.

Keeping the public informed on case developments, holding meetings with victims’ associations, and providing regular updates on judicial proceedings are essential for rebuilding trust.

The clearer and more public these steps are, the stronger the ability of civil society and human rights organizations to monitor the process, press for answers, and ensure that no accused figure escapes justice, according to Koraby.

Sources

- Anger Erupts in Deir ez-Zor as Governor Complains: 'At Least Inform Them' [Arabic]

- Former MP Arrested: Led al-Qatarji Militia and Headed al-Fotuwa Club [Arabic]

- Bringing Back the Shabiha and Gray Men: A Blow to the Revolution and Its Memory [Arabic]

- Fadi Saqr, Accused in the Tadamon Massacre, Sparks Outrage with Reconciliation Deal [Arabic]

- Syria: National Commission for Transitional Justice Outlines Its Plan [Arabic]

- Anger in Aleppo: Al-Marsoumi Launders His Money with Donation to 'Aleppo the Best for All' [Arabic]