Rising Security and Service Challenges: Testing the Future of Yemen’s New Government

People in Yemen are pinning their hopes on this lineup as a “government of rescue.”

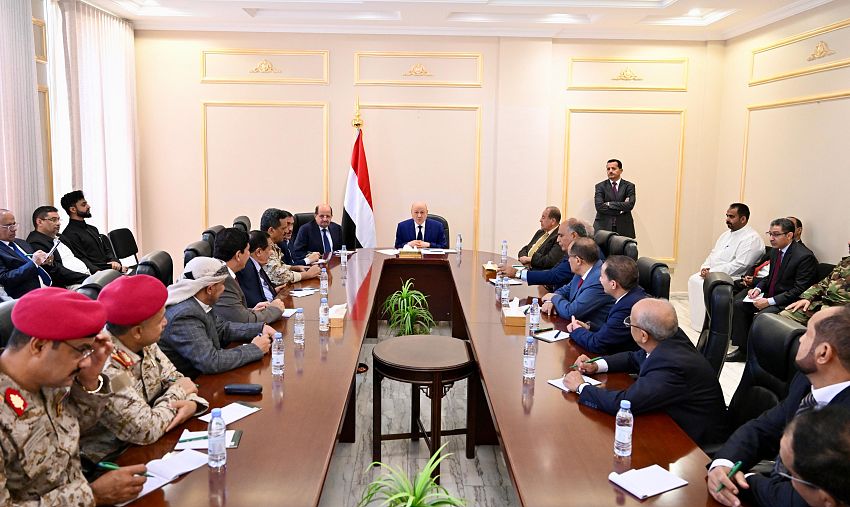

In a move aimed at reshuffling the executive branch and offering a glimmer of hope to a crisis-weary public, Presidential Leadership Council (PLC) Chairman Rashad al-Alimi issued Republican Decree No. 3 of 2026, forming a new government headed by Shaea al-Zandani, who will also retain the foreign affairs portfolio.

The cabinet formation comes as part of the PLC’s effort to inject new blood into state institutions and reset government priorities. The change is not merely a swap of names; it places the new government squarely in front of heavy files, foremost among them the cost-of-living crisis, currency stabilization, and the reactivation of state institutions across all governorates.

On the street, Yemenis are pinning their hopes on the new lineup to function as a “government of rescue,” one capable of bridging internal divisions, restoring state presence, and improving government performance amid mounting challenges.

The government consists of 35 ministers, including 20 from southern governorates and 15 from the north—a distribution that reflects the complexity of the current political landscape and efforts to accommodate competing forces, while also underscoring the persistent problem of an oversized executive.

Politically, the lineup reinforces the dominance of power-sharing and political bargaining in government formation. The General People’s Congress secured six ministerial posts, compared with three for the Yemeni Islah Party and four for the Socialist Party, including one minister of state, while the Nasserist Unionist People’s Organization received a single portfolio.

The Southern Transitional Council (STC) was awarded five ministers, including a minister of state who also serves as Aden’s governor. The cabinet also includes six figures described as technocrats and five ministers from the Hadramout Tribes Confederacy (HTC), among them one minister of state.

The formation process reflects the balance of power within the PLC, where compromise and conflict management outweighed efforts to assemble a government built around a clear reform agenda.

Ultimately, the cabinet appears designed to preserve a minimum level of political and institutional cohesion and prevent a power vacuum, rather than tackle the structural issues tied to the distribution of authority and mechanisms of governance.

How It Came Together

The announcement of the new government marks a significant turning point in the structure of Yemen’s internationally recognized authority. The formation was not a routine cabinet reshuffle but the outcome of a complex political and military process that reshaped power balances in the liberated areas.

The lineup followed nearly three weeks of intensive consultations in Riyadh, aimed at easing tensions among factions operating under the umbrella of legitimacy.

Domestically, the cabinet reflects the PLC’s push to end what officials describe as “institutional erosion” under the previous government. The formation was preceded by a series of consequential political moves, including the appointment of new members to the council—such as Lt. Gen. Mahmoud al-Subaihi and Salem al-Khanbashi—to fill gaps and broaden representation.

The government’s birth also coincided with measures that reduced the influence of the STC as an autonomous governing entity in Aden, effectively integrating it into state frameworks following intense political and military tensions that preceded the announcement.

The cabinet was unveiled amid a series of field developments that gave the legitimate government a relative upper hand in southern and eastern governorates. Authorities regained full control over Hadramawt and al-Mahra and moved to stabilize security in the temporary capital, Aden.

At the same time, the Supreme Military Committee (SMC) was reactivated to integrate armed formations under a unified operations room, creating a relatively secure environment for the government’s return and the conduct of its duties from inside the country.

Regionally, Saudi Arabia played a central role in engineering both the political consensus and the surrounding conditions. The move reflected a Saudi push toward economic stabilization, underscored by a roughly $3 billion financial support package to cover salaries and fiscal obligations, providing a financial “safety net” for the new cabinet.

According to Reuters, Saudi Arabia is leveraging its strategic political influence and injecting billions of dollars in an effort to consolidate control over Yemen following the UAE’s exit last year—signaling Riyadh’s attempt to reassert its regional role after years of prioritizing domestic agendas.

Yemeni officials say Saudi Arabia is seeking to register a success story in areas controlled by the Saudi-backed, internationally recognized government. In this context, Riyadh has pushed to resolve disputes within the anti-Houthi camp to focus either on peace tracks or a comprehensive confrontation.

The government was formed amid a phase of relative de-escalation with the Houthis, alongside indirect negotiation tracks and shifts in the positioning of regional actors. This context shaped a cabinet designed as a transitional, management-oriented government—one meant to adapt to a calm-down and avoid steps that could disrupt existing political tracks.

Internationally, the formation comes as global engagement on Yemen has relatively waned, with external attention narrowed to specific concerns, notably maritime security, counterterrorism, and containment of the humanitarian crisis.

This dynamic resulted in tacit international acceptance of a “functional” government, without meaningful pressure to adopt a comprehensive reform agenda or provide broad economic support.

The cabinet was also formed amid stalled Riyadh talks among southern factions and alongside escalating popular mobilization led by the STC, which intensified street actions opposing the PLC and Saudi Arabia’s role—accused by the STC of backing political arrangements that fall short of southern aspirations.

A southern official said Riyadh informed southern parties that the future of the south is an internal matter, but that any major shifts would remain deferred until the Houthi file is resolved.

The secessionist escalation has unfolded amid the notable absence of STC President Aidros Alzubidi from public view, alongside circulating rumors of his death following Saudi airstrikes that allegedly targeted an STC meeting and weapons depots in al-Dhalea province in early January.

Amid mixed reactions to the new cabinet, the HTC and the Inclusive Hadhramout Conference (IHC) voiced strong objections to the mechanisms adopted by the PLC, arguing they represent a continuation of a traditional political approach that has failed to produce a genuine breakthrough in Yemen’s crisis.

Both groups criticized what they described as cosmetic fixes and temporary solutions lacking a comprehensive national vision to address core issues, reiterating their commitment to Hadramawt’s self-rule project as a strategic option to achieve stability and safeguard the governorate’s political and economic rights.

By contrast, the Yemeni Islah Party, through its representative on the PLC, Abdullah al-Alimi, called on political, social, and media forces to rally behind the technocratic government to ensure its success in confronting current challenges.

He said the cabinet is launching with Saudi backing, national will, and an urgent priority program focused on improving security, services, and development in liberated areas; strengthening stability; meeting basic obligations—chief among them the regular payment of salaries; supporting the families of fallen and wounded fighters; and empowering local authorities in a way that reinforces internal cohesion and advances the restoration of the state and the extension of its sovereignty.

New Challenges

Observers say the new cabinet has served as a “pivot point” for narrowing sharp internal rifts, particularly after integrating key political and military factions into the state structure—an effort that reduced the room for maneuver of parallel power centers that had previously hampered government performance from within the temporary capital, Aden.

The al-Zandani government now faces a real test in the eyes of the Yemeni public across several key files, most notably:

Services: Living conditions top the priority list. Analysts agree that the government’s success will not be measured by policy papers but by its ability to translate regional support into tangible improvements in basic services—especially electricity and water—and to restore confidence in the banking sector.

The Southern Transitional Council: The STC is engaging the new government through a pragmatic approach that combines continued participation in internationally recognized institutions (where it holds five ministerial posts) with the preservation of its own political agenda. Containing the STC, politically and militarily, will be a cornerstone for stability in the south, recovery, and any credible path toward state-building.

The Houthi file: The government’s ability to confront Houthi threats to international shipping, secure Yemeni ports, unify national efforts against the Houthis, push them inland, and impose greater political and military isolation would mark a major success in negotiations and the broader political settlement. Failure on this front, however, would likely shorten the government’s lifespan.

Overall, the new Yemeni government is operating in an exceptionally complex political environment defined by fragmented loyalties, competing priorities, and heavy reliance on Saudi support for its stability.

According to observers, the cabinet is less the product of a moment of political recovery than a reflection of the distortions and complexities of the transitional phase. It is a government built around managing balances rather than resolving them, containing conflicts rather than dismantling them—leaving its core mission focused on preventing collapse and securing a minimum level of stability rather than charting a new national course.

Regional backing may buy the government some space, but without a unifying political vision and amid competing power centers, its future depends more on the course of the conflict than on its own capacity to end Yemen’s crisis.

Sources

- New Government Formed by Presidential Decree, Members Announced [Arabic]

- Saudi Arabia Provides New Support to Yemen Worth 1.9 Billion Riyals [Arabic]

- Aden TV: Aidros Alzubidi Dead in Airstrikes, Claims Muhammad al-Naamani [Arabic]

- STC Members in Sayun Burn Pictures of Saudi Leadership and National Flags [Arabic]

- HTC and IHC Slam New Government Formation [Arabic]

- Abdullah al-Alimi Urges National Cohesion to Back New Government Against All Challenges [Arabic]