From Paper to Phone: ‘Israel’s’ New Digital Strategy for al-Aqsa Bans

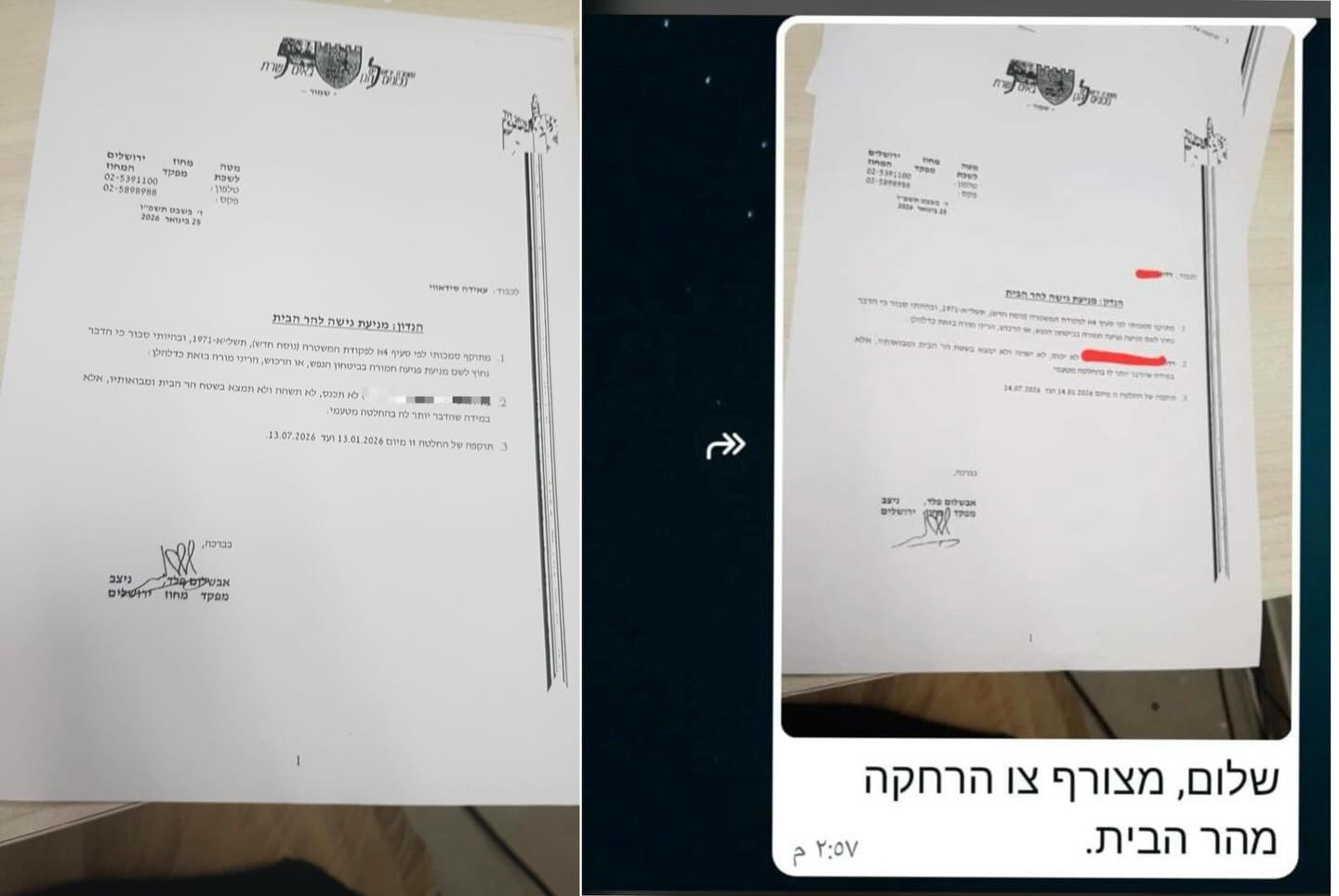

The messages, titled “Barring From al-Aqsa,” came with digital copies of the orders attached.

In an unprecedented move, dozens of Jerusalem residents in recent days received messages via WhatsApp from numbers attributed to Israeli intelligence, informing them that orders had been issued barring them from al-Aqsa Mosque.

The messages, sent under the heading “Barring From al-Aqsa,” were accompanied by digital copies of the expulsion orders, including the name of the person barred, their ID number, and the duration of the order.

The messages sparked widespread shock in Jerusalem, where the step was viewed as a significant and dangerous escalation in the policy of restricting worshipers and those maintaining a presence at the al-Aqsa compound.

Digital Barring

Jerusalem residents targeted by the measures said the barring notices reached them in digital form, without any prior official summons or paper delivery, in an unprecedented step.

With a single click, dozens found themselves banned from entering al-Aqsa Mosque for varying periods ranging from one week to six months, without undergoing the usual procedures of investigation or being summoned to police stations or courts.

Observers said the decision by Israeli intelligence officers to use messaging applications to deliver the barring orders stemmed from the sharp rise in the number of people targeted in the campaign.

With the approach of the holy month of Ramadan, Israeli authorities chose to issue dozens of barring orders at once through text messages, saving time and avoiding the need to summon each person individually.

This method, now referred to as “digital barring,” provides Israeli authorities with a new means of expanding the circle of those banned from al-Aqsa Mosque, in a step that recurs annually ahead of Ramadan.

In this context, Jerusalem and al-Aqsa affairs specialist Radwan Amr said he received a decision renewing his ban from al-Aqsa for six months through a message on WhatsApp.

The platform Alquds Albawsala quoted Amr as saying, “I received the message from an unknown number affiliated with Israeli police, and this is unprecedented for us. It appears to have come as a result of the high volume of bans and the large number of those barred.”

Amr had received, on January 14, 2026, a decision barring him from al-Aqsa Mosque for one week, renewable, before he was later summoned and verbally informed that the ban had been extended until further notice. The written decision was subsequently sent to him via WhatsApp.

According to the Wadi Hilweh Information Center, Silwan, the barring orders included employees of the Islamic Endowments Department, formerly imprisoned Palestinians, and Jerusalem-based activists.

Mohammad al-Dabbagh and Hamza Khalaf, both employees of the Islamic Endowments Department, received one-week barring orders renewable for several months. The measures also targeted formerly imprisoned Palestinians, Jihad Qous and Wissam Kastero.

Israeli authorities also issued four-month barring orders against formerly imprisoned Palestinians Abdulrahman Oweis and Hamza Abu Hadwan, according to the same source.

Meanwhile, six-month barring orders were issued against a number of formerly imprisoned Palestinians, including Kifah Sarhan, Areen Zaneen, Sohaib Affaneh, Mohammad Mousa al-Abbasi, Tareq Saadeh Abbasi, Ibrahim Abbasi, Mousa Abu Tayeh, Sami Abu al-Halawa, Obaida al-Taweel, Amer Bazlamit and Maamoun al-Razam.

The measures were not limited to men. Israeli authorities have barred about 60 Palestinian women from Jerusalem from entering al-Aqsa Mosque for years, listing their names on what they describe as a “blacklist.”

Jerusalem residents who received the WhatsApp notifications said the unprecedented method went beyond even the traditional administrative mechanisms Israeli authorities have typically followed.

Observers said it has become clear that the primary aim of the step is to accelerate and intensify the issuance of barring orders as Ramadan approaches, in an effort to reduce the Palestinian presence at al-Aqsa Mosque to the lowest possible level.

An Escalating Pace

Recent statistics revealed an unprecedented rise in the number of people barred from al-Aqsa Mosque ahead of Ramadan 2026.

According to data issued by the Jerusalem Governorate, about 100 barring orders were issued in January 2026 alone, including 95 directly related to al-Aqsa Mosque.

This escalating pace far exceeds what was recorded in previous years. The governorate documented about 200 barring cases throughout 2024, including 149 bans from al-Aqsa, while the number of bans since the start of 2026, in just one month, is estimated to be nearly equivalent to the total for the previous year.

The wide-scale barring campaign has coincided with tightened security measures that Israeli authorities have routinely imposed each year ahead of Ramadan.

Israeli police have intensified their deployment in Jerusalem and set up fixed and mobile checkpoints. In mid-January, they also recommended restricting the entry of Palestinians from the West Bank into the city during the holy month.

In the same context, Israeli security agencies announced they had entered a phase of “preemptive preparations,” including carrying out arrests against those they describe as “inciters,” who are in practice Jerusalem-based activists who continue to confront settler incursions into al-Aqsa Mosque, with the aim of neutralizing any potential popular mobilization within its courtyards.

Experts and observers of Jerusalem affairs said the inclusion of the recent barring orders to cover both Ramadan and what is known as the Jewish holiday of Passover is not incidental, but rather aims to enable Israeli authorities to push through serious violations and provocations during the two occasions, away from the presence of worshipers and Jerusalem activists.

The adoption of what has been termed “electronic barring” has sparked wide debate over its legality and has been described as a blatant violation of freedom of worship as guaranteed under international laws and conventions.

Barring Palestinians from their mosque through a phone message, without a clear legal basis or judicial procedures, is viewed as a dangerous precedent underscoring the arbitrary nature of these decisions.

The Israeli escalation has not been limited to the method of notification, but has also extended to the substance of some barring orders.

The term “Temple Mount” has been inserted to refer to al-Aqsa Mosque, a move carrying serious implications as it reinforces the Judaization narrative of the site and violates the existing historical and legal status quo governing the al-Aqsa compound.

Analysts said the insistence by Israeli police on imposing such terminology and restrictions marks the beginning of a new phase in efforts to assert alleged Israeli sovereignty over al-Aqsa Mosque, within broader attempts to entrench the temporal and spatial division of the site.

In response, Palestinian officials and religious figures warned of the serious repercussions of these policies. Sheikh Ekrima Sabri, the preacher of al-Aqsa Mosque, cautioned that the mass barring orders and restrictions imposed ahead of Ramadan constitute a clear attempt to undermine the status quo at the mosque.

He held the Israeli government fully responsible for any deterioration or escalation resulting from the continuation of these violations.

The Palestinian Ministry of Endowments, along with other official and civil institutions, also condemned the measures, saying they expose what they described as the false claims by Israeli authorities of respecting freedom of worship. They asserted that the real objective is to empty al-Aqsa Mosque of Muslim worshipers and impose Israeli control over it by force.

Administrative Notice

Marouf al-Rifai, media adviser to the Jerusalem Governorate, said the shift in the barring policy from paper notices to instant notifications effectively accelerates implementation, without the need for direct confrontation or formal delivery, reducing Jerusalem residents’ ability to file legal objections or gain time to challenge the decisions.

Al-Rifai told Al-Estiklal that the move is intended to create a sudden psychological shock, as the decision arrives abruptly on a phone, without a clear legal context, explanation, or review and appeal mechanism.

He added that Israeli authorities are seeking to turn barring into a “rapid routine” measure, closer to an administrative notice than to a consequential decision affecting fundamental rights such as freedom of worship, residency, and movement. He said the approach reflects what he described as the “smart management mentality of the occupation,” based on “minimal human contact and maximum technical control.”

Al-Rifai said the policy carries a collective message of intimidation rather than an individual one. Although the order is addressed to a specific person, the broader aim is to signal to all Jerusalem residents that they are subject to digital surveillance and to reinforce the sense that Israeli authorities are present in their phones, homes, and streets alike.

He said the approach leads to a generalized state of preemptive deterrence, conveying that “anyone could be next,” adding, “We are facing a remotely managed digital architecture of fear.”

Regarding the timing of the policy, al-Rifai stressed that its implementation ahead of Ramadan is not coincidental. “Choosing this period reveals the primary objective, to empty the city of activists and those maintaining a presence before the peak of public attendance at al-Aqsa Mosque,” he said.

He said Israeli authorities aim to prevent the formation of a broad popular mobilization as is customary during Ramadan and to preempt any potential protest movement or field escalation. “In other words, Israeli authorities are attempting to sterilize Jerusalem from a security standpoint before the most sensitive religious season,” he said.

Al-Rifai also pointed to another objective, entrenching barring as a central tool for managing the city. He said barring is no longer an exceptional measure but has become a permanent policy to clear the Jerusalem scene of active figures, an alternative to prolonged detention, and a means of dismantling social and national networks within the city.

“What makes the current phase more dangerous is that barring is now being used with high technical flexibility and without effective judicial cover,” he added.

He said Israeli authorities are moving toward governing the city through digital punishment within a broader model based on electronic surveillance, digital orders, and tracking through applications, issuing security decisions without paper documentation. This, he said, marks a shift from field control to algorithmic control over the lives of Jerusalem residents.

“What we are witnessing is not merely a change in the method of notification, but a systematic escalation in the barring policy, an attempt to reengineer Jerusalem’s public space ahead of Ramadan, a test of new digital repression tools and a clear effort to break popular will through instruments that may appear soft on the surface but are harsh in substance,” he concluded.

According to al-Rifai, “It is a new phase in the management of Jerusalem, an occupation without queues, repression without papers, and decisions that arrive with the sound of a phone notification.”

Sources

- Escalation of Summonses and Expulsion Orders From al-Aqsa Mosque as Ramadan Approaches

- Jerusalem: 4,397 Colonists Stormed al-Aqsa Mosque, 103 Detentions, and 86 Demolition and Land-Leveling Operations in January 2026

- Israel Is Banning More and More Palestinian Figures From Entering al-Aqsa Mosque on Arbitrary Grounds