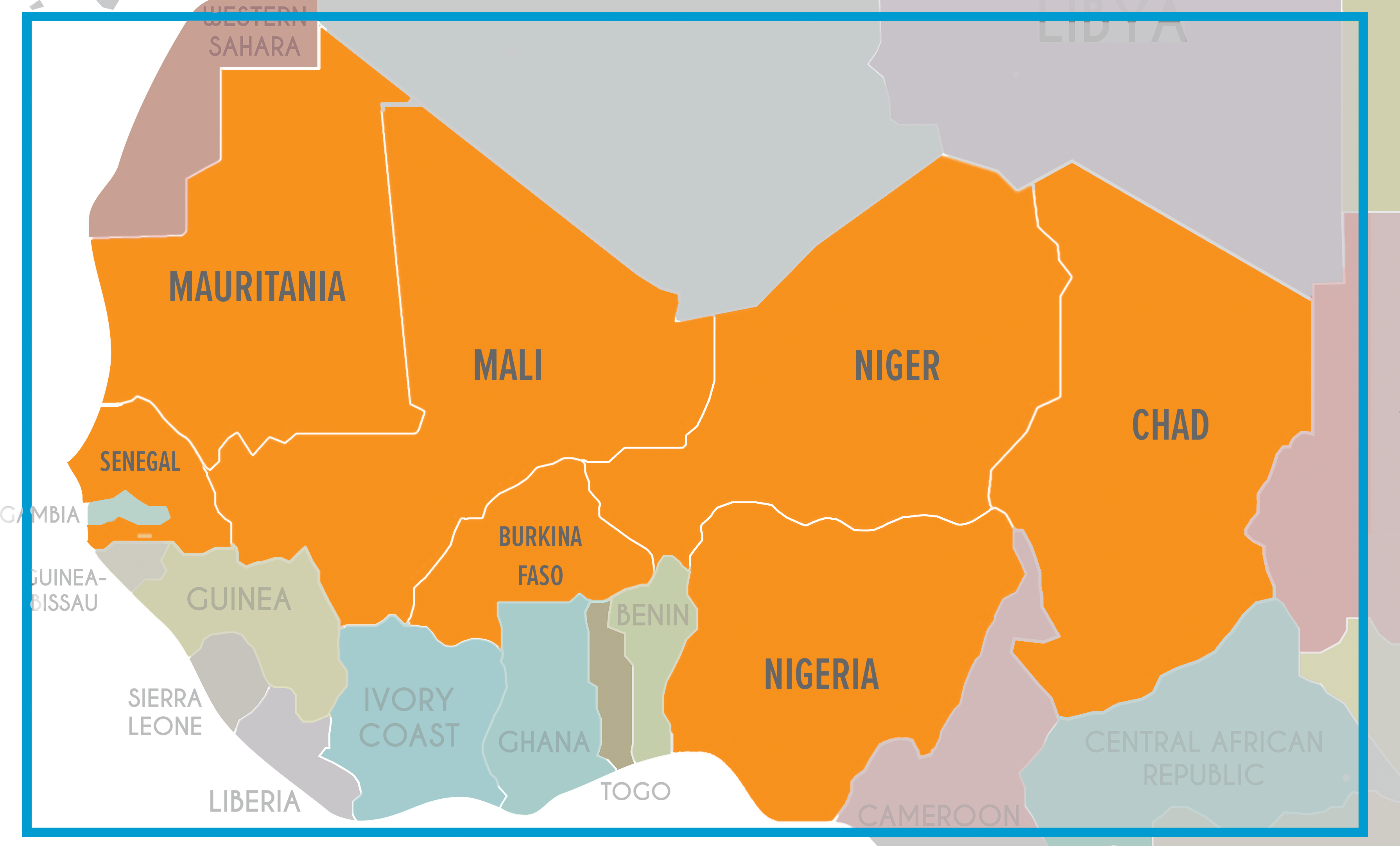

Despite Withdrawing Its Armies: How the West Continues To Control West African Countries

“The West has recently realized that its direct military presence in West African countries is seen as a source of resentment.”

West Africa, specifically between 2021 and 2025, witnessed a pivotal security shift marked by a wave of military coups that resulted in the expulsion of official Western forces from key countries such as Niger, Mali, and Burkina Faso. This raised serious questions about the extent of the decline in American and European influence in the region.

Despite talk of the withdrawal of all Western forces from West African countries, in-depth analyses have revealed that the West, in both its American and European forms, has not completely withdrawn from the African continent, but has restructured its security presence to become more pervasive and less visible, replacing traditional military deployment with advanced technology and covert networks.

This shift stems from the West's realization that a direct military presence is now perceived as a source of resentment and is exploited as fuel for anti-colonial propaganda promoted by Russia and China.

Consequently, the West opted for a more covert approach, relying on remote control through drones, satellites, private security companies, and local proxies.

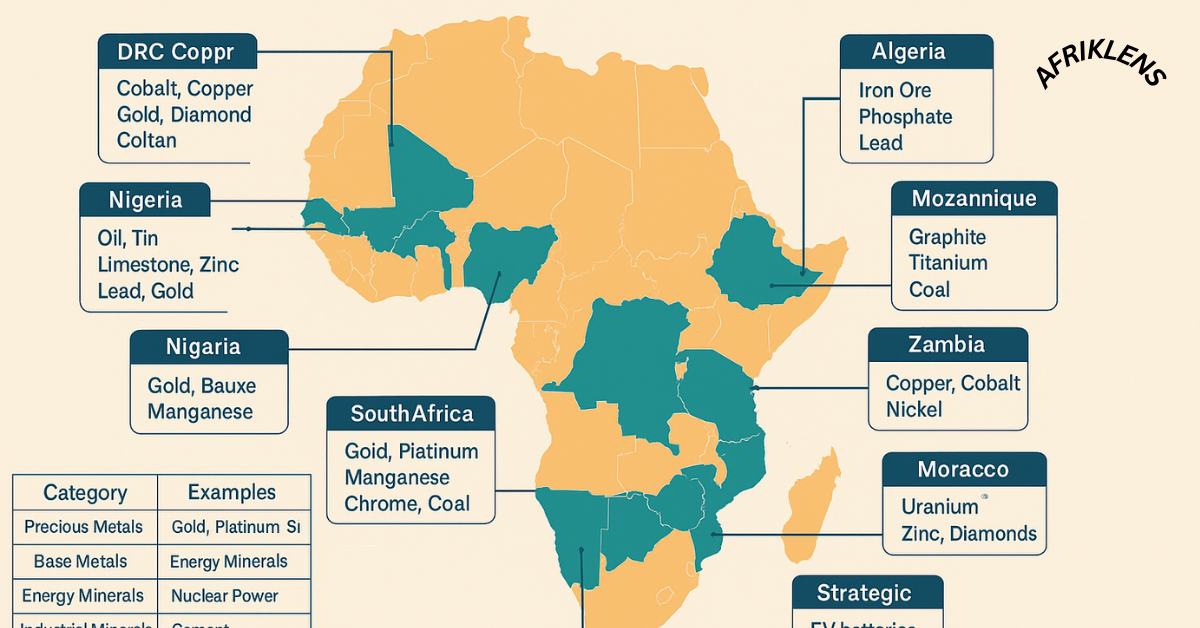

This strategy is not merely a defensive approach but an offensive plan aimed at protecting vital economic interests, such as securing uranium resources in Niger, gold in Ghana, and oil in Nigeria, while simultaneously combating terrorist threats posed by groups like ISIS and al-Qaeda in the Sahel region.

Reports from prominent international organizations such as the International Crisis Group and Human Rights Watch indicate that this approach has increased reliance on artificial intelligence and electronic surveillance, enhancing the West's ability to respond quickly without engaging in long-term commitments or direct confrontations with international rivals, such as Russia, which has strengthened its presence through mercenary groups.

Ongoing Operations

Between 2023 and 2025, Niger witnessed the symbolic fall of the Agadez stronghold, which housed the French 101st Air Base and the US 201st Air Base, dedicated to drones and the largest of its kind for the CIA and AFRICOM in the world.

This fall did not mark the end of Western influence, but rather the beginning of a more flexible and sophisticated strategy.

Unlike France, which was immediately expelled after the July 2023 coup due to its historically colonial rhetoric, the United States maneuvered for over a year before announcing its complete withdrawal from the Agadez base in August 2024, but maintained small liaison cells for intelligence coordination with the Nigerien military junta.

The primary tactic here is the shift to an over-the-horizon (OTH) surveillance model, relying on advanced satellites such as those belonging to Maxar or the US Space Surveillance Program, as well as long-range drones like the Reaper, launched from bases outside Niger, such as those in West African countries like Ghana or the Ivory Coast.

This strategy has given Washington the ability to monitor Nigerien airspace and identify any terrorist targets without the need for a single soldier on the ground. This has allowed counterterrorism operations against groups like ISIS in the Sahel region to continue without the risks of political escalation or human losses.

Furthermore, the tacit US agreements with the Nigerien military junta, led by General Abdourahamane Tiani, rely on indirect pressure mechanisms, such as humanitarian aid through the US Agency for International Development (USAID) and the World Bank, to compel the regime to maintain open intelligence channels. This is justified by the shared interest of ensuring the continued flow of uranium from the Arlit mines, operated by the French company Orano, despite the tensions that led to partial nationalization in 2025.

In Mali and Burkina Faso, both countries, which have witnessed declared alliances with Russia through the Africa Corps (formerly Wagner Group), have seen these alliances lead to the expulsion of official Western forces, such as the French Operation Barkhane and the European Operation Takuba.

However, the West has resorted to security privatization as an effective alternative strategy to maintain its influence, representing an analytical shift towards using private companies to counter Russian influence without direct political costs or human losses.

Bancroft Global Development, which presents itself as a U.S.-based non-profit organization specializing in mine clearance but is in reality a private military company staffed by former special forces experts, has emerged as a key tool here.

This company has negotiated and attempted to gain access to Mali and Burkina Faso to provide training and security services, thus maintaining a Western foothold in capitals like Bamako and Ouagadougou without provoking anti-colonial African public opinion.

The strategic objective of these companies is to provide more technically competent mercenary groups, focusing on training local elite units to conduct ground operations, thereby enhancing Western stability in the region without the need to deploy official forces, as has been the case previously. In the Central African Republic, Bancroft successfully tested the waters of the security market.

Furthermore, the West enjoys overwhelming superiority in cyber intelligence through the US National Security Agency (NSA) and the French Directorate General for External Security (DGSE).

Both agencies continue to intercept phone calls, monitor the movements of armed groups, and even intercept communications between coup plotters and Russia.

They also present some of this intelligence as a trap to the ruling regimes in Mali (under Colonel Assimi Goita) and Burkina Faso (under Captain Ibrahim Traore) to demonstrate the superiority of Western technology over Russian technology.

This approach reflects the West's success in adapting to the Alliance of Sahel States (AES), formed by Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso in 2023.

Security privatization has become a tool for maintaining geopolitical balance in West Africa, despite criticism from human rights organizations such as Amnesty International regarding the potential role of these companies in human rights abuses without accountability.

African Interests

Senegal and Côte d'Ivoire, which were relatively spared from the wave of coups in West Africa, transformed during the period 2021-2025 into what are known as the West's land-based aircraft carriers.

The two countries became alternative command and control centers for repositioning US and European forces away from the Sahel's volatile regions, reflecting a strategy of containing terrorist threats without direct military expansion, which had previously failed.

For the United States, AFRICOM is leading this shift under the direction of General Michael Langley, who made shuttle visits to Côte d'Ivoire and Senegal in 2024 and 2025 to negotiate the establishment of drone bases.

This aims to shift the military focus from the Sahara (such as Niger) to the Sahel (Gulf of Guinea), securing vital routes that transport oil from Nigeria, cocoa from Côte d'Ivoire, and minerals from Ghana to Europe and America, with a focus on protecting economic interests in the face of growing Chinese competition.

For Germany, France, and Spain, the model has shifted to that of a military development partner, where the military presence has transformed into training and logistics hubs, as is the case in Senegal.

Benin and Togo, which have become the new hotspot in West Africa as terrorism spreads south from the Sahel, represent the West’s new line of defense.

The United States and Europe are focusing on a border shield program that pours millions of dollars under the guise of border security, but the reality goes beyond that to include the installation of advanced American radars and thermal and biometric sensors on the northern borders with Niger and Burkina Faso.

These advanced technologies are also linked to Western databases, such as those of Interpol or the National Security Agency (NSA), meaning the West can see and hear everything entering and leaving the Sahel region without deploying ground troops.

This program, funded by hundreds of millions of dollars through the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and the European Commission, includes training local forces to use this technology, reinforcing African dependence on the West and preventing the spread of terrorism southward into the Gulf of Guinea.

In addition, very small teams of U.S. (Green Berets), French, and British (SAS) special forces are deployed to train elite units in Benin and Togo.

This approach has helped protect economic interests, such as oil fields in neighboring Nigeria, but it deepens dependence on Western technology.

There have also been reports of U.S. negotiations to establish new bases in the region, raising concerns about privacy and sovereignty in light of increased surveillance. Electronic.

Western Influence

The essence of Western tactics in West Africa lies in replacing traditional military intervention with advanced technology. This strategy focuses on drones and satellites for constant surveillance, and private security companies to fill the military vacuum.

It also involves establishing a presence in coastal states—such as Senegal and the Ivory Coast—to either isolate or remotely monitor other Sahel countries, thus ensuring sustained influence without significant human losses or political risks.

For the United States, the de facto new manager, this strategy relies not on a single company but on a complex network of contractors, such as Bancroft Global Development, which conducted negotiations in Mali; Sierra Nevada, which modified reconnaissance aircraft; and Amentum, which provided logistical support.

Key figures include General Michael Langley, who engineered the coastal wall, and Assistant Secretary of State Molly Phee, who negotiated with Niger, reinforcing the analysis that Washington is focusing on soft containment to prevent a security breakdown.

In turn, France recycles its influence through companies like Amarante International and GEOS Group, and energy companies like Orano and Total, along with figures like Jean-Marie Bockel and Bernard Emié.

Local agents, such as Alassane Ouattara (President of Côte d'Ivoire) and Patrice Talon (President of Benin), reinforce Western control, with clandestine operations such as the Agadez Capacities Transfer and the Ivorian Counterterrorism Academy.

In Nigeria, private armies, like SPY Police and companies like G4S and Control Risks, protect the Niger Delta, while Ghana and Liberia rely on Western laws to safeguard investments.

Mauritania combats illegal immigration through Frontex, Guinea protects its aluminum production, and Cape Verde serves as a transit hub.

The result is a less costly and more effective form of influence that safeguards Western interests against competitors.

Western Propaganda

The violent and radical political transformations and the spread of a revolutionary nationalist discourse rejecting neo-colonialism and demanding full sovereignty in most West African countries over the past years have prompted the Western illusion factory to operate with high efficiency and meticulous precision.

Consequently, the West has created a comprehensive narrative system based on soft power to justify the plundering of rich natural resources, such as uranium in Niger, gold in Mali, gas in Senegal, and cocoa in the Ivory Coast.

The West has used media, culture, humanitarian aid, and NGOs as key tools to reframe reality and transform it from colonial exploitation into a necessary partnership, humanitarian assistance, or development cooperation.

This narrative is not merely spontaneous propaganda or a reaction to events, but a well-thought-out and well-funded strategy aimed at maintaining economic and security dominance in light of the decline of direct military presence, which has become politically and humanly costly.

Thus, the West portrays itself as the savior from terrorist chaos or the trustworthy partner in sustainable development.

Several international reports in 2025 confirmed that over 70-80% of profits from investments in mining, energy, and agriculture accrue to parent companies in Paris, London, New York, and Toronto, while the GDP of African countries continues to stagnate.

In countries like Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso, as well as dependent states such as Senegal, the Ivory Coast, Benin, and Togo, France is waging a fierce and organized media war to regain the moral legitimacy it lost after the withdrawal of its forces in 2022-2024.

This involves employing a comprehensive media machine, funded by the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs with annual budgets reaching hundreds of millions of euros, to portray the French withdrawal as a direct cause of chaos and terrorism, and France as the protective father or benevolent mother to whom these countries must return for survival.

The United States skillfully employs Hollywood and educational soft power, as exemplified by the YALI – Mandela Washington Fellowship, which takes the brightest young minds from Nigeria, Ghana, and Sierra Leone and trains them for weeks at prestigious American universities in entrepreneurship, liberal democracy, and technological innovation.

Ultimately, these individuals return to their countries to become ministers, CEOs, or activists, firmly convinced that the American model is the only path to development and that American companies like Chevron, Newmont, or Cargill are the ideal partners for prosperity, thus creating a new generation of pro-American elites.

In turn, Britain uses reputation and the English language as soft power tools. BBC Africa enjoys very high credibility among Africans, promoting terms like international investors instead of plundering corporations, and necessary reforms instead of the harsh austerity conditions imposed by the IMF.

The British Council and Chevening Scholarships offer thousands of opportunities annually to study at British universities like Oxford and London, creating long-term class loyalty.

This is evident in graduates who have become judges or ministers in Ghana, Sierra Leone, and Liberia, ensuring that mining and investment laws are written in ways that protect British companies like Tullow Oil or Rio Tinto.