How Europe Adopts New AI Methods to Turn Migrants Away

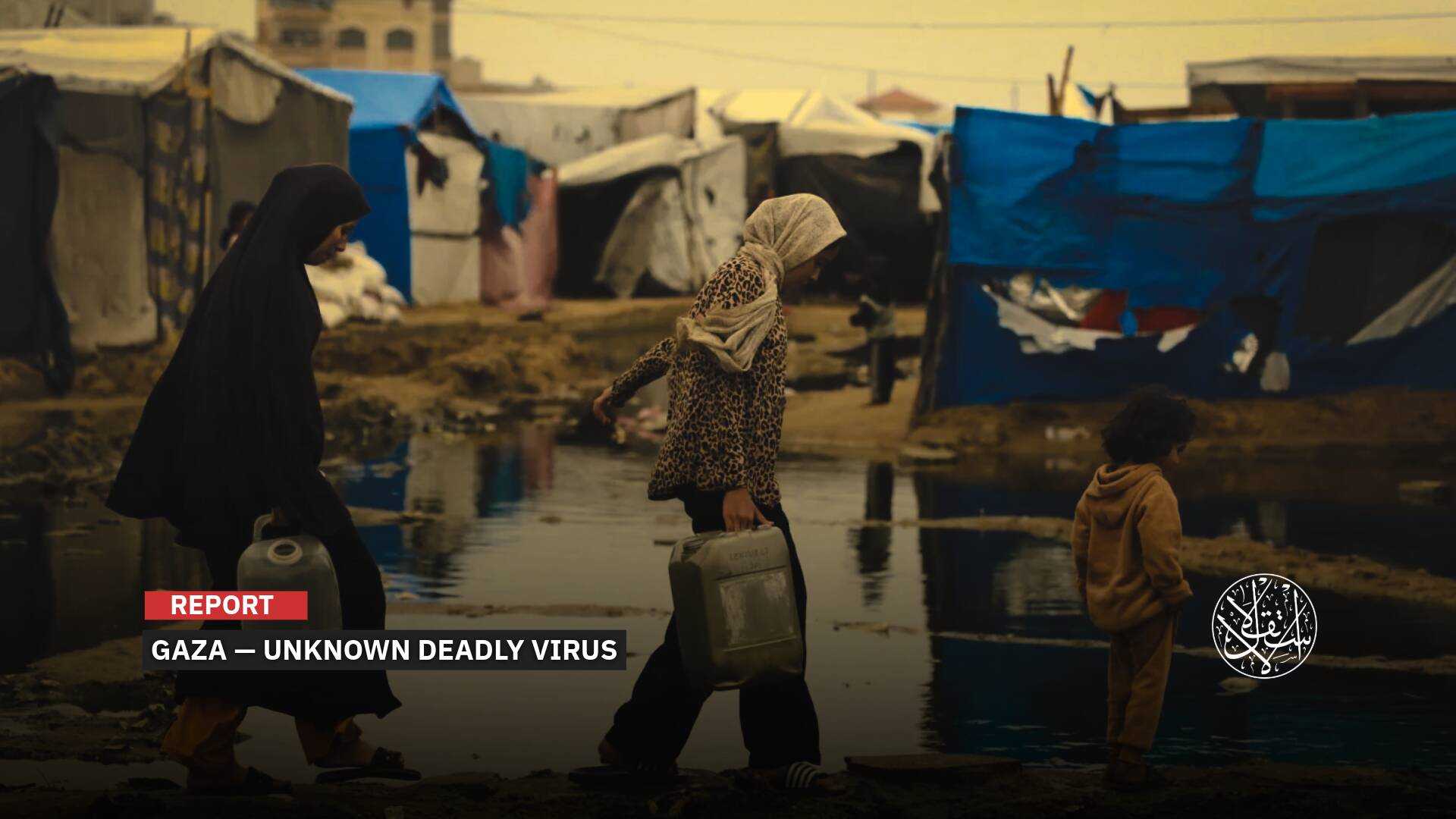

Dubbed the “migrant crisis,” over a million people seek asylum within the European Union annually.

As we approach the tenth anniversary of the migration surge to Europe from Africa and the Middle East, the impact of this historic movement continues to shape policies and provoke debate.

Dubbed the “migrant crisis,” over a million people seek asylum within the European Union annually. The numbers have remained high, even as the dynamics have shifted.

To control the influx of migrants, the European Union and its member states have adopted stringent closed-door policies.

These measures include bolstering external borders and implementing anti-immigration strategies to render Europe increasingly “immune.”

New Regulations

The Conversation newspaper conducted a report about Africa-EU relations and migration policy, closely monitoring developments over the past decade.

Drawing on various sources and contacts, The Conversation noted that European countries have significantly fortified their borders, diverting resources to manage entry points.

The total length of border fences along external and internal EU boundaries has surged from 315 km in 2014 to a staggering 2,048 km by 2022. Military forces now play a more active role in managing migration.

Moreover, non-governmental organizations advocating for migrants face increasing harassment. Europe-based organizations working to protect migrants’ rights encounter obstacles as they navigate the complex landscape of border enforcement.

According to the newspaper, the asylum process is increasingly outsourced to African countries. This controversial approach aims to prevent migrants from reaching European shores by shifting responsibility elsewhere.

While physical barriers dominate the discourse, technology also plays a pivotal role, as artificial intelligence, used for risk assessments, can inadvertently perpetuate discrimination based on race and origin. Unlawful profiling and racism remain concerns.

Additionally, The European Parliament’s recent Charter on Migration and Asylum permits facial recognition technology and biometric data collection. Migrants’ photos and information can now be stored for up to a decade, accessible to police forces across the EU.

Military-grade drones patrol the Mediterranean, aiding Coast Guard efforts to intercept refugee boats.

However, these technologies raise questions about immigrants’ rights, privacy, and potential discrimination.

In the face of these developments, Europe grapples with balancing security and compassion. Regardless of the measures taken, irregular migration persists—a reminder that seeking better opportunities is an intrinsic part of human existence.

AI Abuses

The deployment of new technologies aimed at automating EU border security systems has sparked multiple human rights concerns.

While the past and present implications of Fortress Europe have been extensively documented, the potential future impact urgently requires attention.

In October 2018, the European Union (EU) announced funding for a novel automated border control system to be piloted in Hungary, Greece, and Latvia.

Dubbed “iBorderCtrl,” the project employs an artificial intelligence (AI) lie-detection system, fronted by a virtual border guard, to interrogate travelers seeking to cross borders.

Those deemed truthful by the system receive a code allowing them to proceed, while others are referred to human border guards for further questioning.

iBorderCtrl represents just one of several initiatives aimed at automating EU borders to address irregular migration. However, this trend raises significant human rights concerns.

The technology behind iBorderCtrl relies on “affect recognition science,” a contentious field.

Proponents claim that analyzing facial features can reveal authentic emotions and personality traits, asserting that emotions are universally fixed and visible across individuals, regardless of cultural context.

Yet, AI facial recognition systems have repeatedly demonstrated inherent biases, reflecting the data used to train them.

Claims of reducing subjective control and increasing objective control through automation are misleading. Researchers have shown that affect recognition lacks scrutiny and is being applied irresponsibly. iBorderCtrl exemplifies this issue.

While the project emphasizes the involvement of a “human border guard” in entry refusals, practical challenges make this guarantee impossible.

The high volume of travelers, potential staff shortages, and political pressures for restrictive border policies increase the risk that decisions will rely on AI judgments.

Testing whether refusal of entry is based on automated decision-making becomes challenging for subjects, data protection supervisors, and courts.

Transparency in technology development is equally concerning. Border agents must rely on opaque systems they do not fully understand, while travelers are expected to trust these automated solutions.

iBorderCtrl reflects a broader EU trend of enhancing border monitoring through technology.

Although traditional security systems intensified after the 2015 influx of asylum seekers, the rise of AI and big data has led to smart border automated security solutions.

In summary, we witness the emergence of techno-solutions that demand careful scrutiny to safeguard human rights and accountability.

Humanitarian Repression

Several European Union (EU) countries have intensified their scrutiny of humanitarian organizations that aid migrants.

These organizations face criminalization, with accusations ranging from smuggling and human trafficking to espionage. Some have even been ordered to refrain from assisting migrants in challenging situations.

For instance, in 2024, the Italian Coast Guard detained a Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) humanitarian search and rescue vessel.

Remarkably, this marked the twentieth time Italian authorities had apprehended a humanitarian ship since the government implemented a new law restricting rescue operations in early 2023.

Similarly, in 2022, Polish officers arrested four human rights activists from the organization Grupa Granica.

These activists had provided food, blankets, and transportation to a family with seven children stranded in a frozen forest along the borderlands between Poland and Belarus. The charges against them included illegal smuggling.

In August 2018, Greek authorities imprisoned 24 aid workers from the International Emergency Response Center. These workers had assisted in rescuing distressed migrants at sea. The group faced accusations of espionage, fraud, human smuggling, and money laundering. However, they were later acquitted.

For years, the European Union and its member states have explored the possibility of outsourcing or subcontracting the asylum process to African countries.

In 2021, the African Union strongly condemned Denmark’s plans to process asylum applications on African soil. Danish politicians argued that this approach would address the shortcomings of their domestic asylum system.

Since 2018, the EU has grappled with the crisis of migrants rescued in the Mediterranean Sea, particularly in North Africa.

Collaborating with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees and the International Organization for Migration, the EU effectively “disposes” of rescued migrants by relocating them to North African nations.

However, this practice has drawn significant criticism due to concerns about migrant safety and rights.

Notably, the non-governmental organization Oxfam reported that the Libyan Coast Guard intercepted 20,000 migrants and returned them to Libya in 2022.

Subsequent reports indicated that the whereabouts of this group remained uncertain. Furthermore, there are disturbing accounts of serious human rights violations against migrants by Libyan authorities.