Exclusive: RSF Schemes May Target Egypt, Libya, and Algeria, Sudanese Politician Warns

“Israel is trying to dismantle the structure of the Sudanese state.”

Mohamed al-Wathiq Abu Zeid, Secretary of Foreign Relations for Sudan’s Future Movement for Reform and Development, said wiping out the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) militia has become a national mission, as Sudanese now realize that what happened in el-Fasher could happen anywhere else in the country.

In an interview with Al-Estiklal, he warned that the militia’s foreign sponsors aim to turn el-Fasher into a major launchpad for wider attacks across Sudan and the region, adding that Egypt, Libya, and Algeria should not assume they are beyond reach.

On the humanitarian crisis, Abu Zeid said Sudan is facing the world’s largest displacement emergency, yet receives barely 10 percent of the aid it needs.

He stressed that the billions the UAE pours into the RSF, like money, weapons, and mercenaries, will ultimately blow back on Abu Dhabi, saying it can no longer whitewash its image.

Abu Zeid, 46, is a Sudanese political figure known for pushing to renew Islamic thought and elevate experts and technocrats in state institutions. Holding degrees in political science and international relations, he focuses on governance and institutional reform.

The Future Movement for Reform and Development positions itself as a national party advocating comprehensive political renewal in Sudan.

The Tragedy of el-Fasher

What, in your view, caused such a dramatic shift in el-Fasher, and what does the spread of fighting to North Kordofan signify?

El-Fasher is no ordinary city. It sits at the heart of centuries-old trade and pilgrimage routes—linking Sudan to Libya, Chad, Niger, and Mali, and once serving as a key stop for pilgrims traveling from West Africa to Mecca. It also has deep historic ties to the Ottoman era through Sultan Ali Dinar’s rule.

Geographically, it anchors western Sudan. The road that connects Omdurman to el-Obeid and then to el-Fasher ties the capital of Darfur directly to Greater Khartoum.

Demographically, the city is a mosaic: it lies within the territory of the large Burki tribe, borders the lands of the Fur tribe, and touches Zaghawa areas that extend into Chad, though most of the Zaghawa population lives in Sudan.

All of this makes el-Fasher a strategic prize for any force in the country.

Attempts to seize the city didn’t begin yesterday; they started more than two years ago. El-Fasher was encircled, and the RSF had already established a major foothold in its southeastern outskirts, including a camp they took after 2019 with the state’s knowledge. Their prior presence—and familiarity with the terrain—made the recent battles even more dangerous.

Even so, the city did not fall easily. It held out until the 268th battle; the RSF had lost 267 times before breaking through. The siege was suffocating. Anti-aircraft guns ringed the city, crippling air-drops, starving residents, and fueling a wave of brutal killings.

People were executed based on identity. Others were killed simply for trying to bring food into the city. Water was cut twice from the main reservoir, Golo, plunging el-Fasher deeper into catastrophe.

This is the grim reality of what the city has endured.

Are recent events a turning point for Sudan or just another chapter in the war?

In my view, they are both: a turning point, and at the same time, another round in a long war.

They mark a turning point because the militia’s backers have clear goals—one of them is carving out an independent Darfur. But you can’t talk about separating Darfur without controlling its capital.

There are also actors pushing a “Libyan-style” scenario as a first step toward fragmentation, two governments inside one country. So in the minds of those supporting the militia, recent events represent a major shift in Sudan’s trajectory.

Yet there are also developments that suggest this could be just one round in a much bigger battle. El-Fasher has united the Sudanese resistance. The Sudanese Army and the Joint Forces—many of whom are from Darfur and once fought against the state before joining the peace process—are now fighting alongside the military. They understand the geography, the terrain, and the militia’s fast-movement tactics better than anyone, and many have personal scores to settle.

The groups that originally joined the militia see these forces as their main competitors in the region. The fighters now aligned with the army are not going to disappear when this war ends.

And the sheer scale of the militia’s crimes, destroying hospitals and infrastructure, and targeting women and children in and around el-Fasher, has hardened public resolve. Sudanese communities are determined to reclaim their land and ensure the militia has no role in Sudan’s future, militarily or politically.

The same pattern of atrocities has appeared in al-Jazirah, Kordofan, and other regions where the militia carried out massacres.

So yes, this is a turning point, because the conflict has now fully exposed the plans of those backing the militia.

Eliminating the RSF from Sudan’s political and military landscape has become a national goal. What happened in el-Fasher could happen elsewhere, and even beyond Sudan’s borders. Libya’s western region is particularly vulnerable.

Most of the weapons used in the war entered through Kufra with support from Haftar’s authorities in Benghazi. This poses a threat across the central Sahara, especially to Algeria, which is also being targeted by the same actors supporting the militia.

Their statements now openly reveal hostility toward Sudan—and even toward Egypt—after years of hiding it. This region borders Egypt and Libya and is close to southern Algeria and the wider Western Sahara.

There are also serious attempts at demographic engineering: bringing in large numbers of communities from outside Sudan and settling them in this region, including el-Fasher, as part of a logistical support network.

El-Fasher has a major airport, just as Nyala’s airport in South Darfur was used for months to support the militia, with flights from the UAE documented through airports in Somaliland’s Bosaso, Chad, and elsewhere.

The militia’s backers hope to turn el-Fasher into a central hub for launching wars across Sudan, especially since part of the weapon supply entered through the Adre crossing near Chad.

The UAE and the Agenda of Fragmentation

Do you expect the UAE to deepen its support for the militia, or might it pull back given the massacre scandals?

The UAE has poured billions into this militia, financing it with weapons and money, and it previously used the same forces in Yemen. This was one of the major mistakes of Sudan’s former regime: allowing the militia to build a direct relationship with Abu Dhabi.

With Emirati backing, the militia grew from around 20,000 fighters to about 120,000, and today the numbers exceed even that. These figures are staggering when you consider that some national armies in the region, like Niger and Mali, have fewer than 10,000 troops.

The UAE has invested heavily, and we do not expect it to stop. Abu Dhabi is betting on this militia to control Sudan and to shape it into a substitute army, even though the militia has lost much of its original fighting force. Current estimates speak of around 120,000 militia members killed in this war, many of them recruited hastily from neighboring countries.

The UAE continues to recruit foreign mercenaries, including from Colombia, as documented in multiple reports. Its support hasn’t stopped, but it is losing: losing on the ground, as the past two years have shown, and losing the image it spends billions trying to polish through sports and public relations campaigns, particularly in Western countries.

Today the world is paying attention to this small state, its behavior, and the money it spends fueling insecurity, killings, and mass atrocities, most notably in Sudan.

Everything the UAE invests, both in whitewashing its reputation and in this militia, will ultimately backfire, especially as it claims politically to support civilian and democratic governance in Sudan. No serious observer can accept such claims, particularly from a country that lacks these values at home.

These developments also come as several countries are beginning to step back from supporting the Emirati line. They now feel directly threatened, realizing that the fire burning in Sudan could reach them. We see shifts in South Sudan, growing pressure in Chad to halt support, and similar dynamics in Somalia and Kenya, where Emirati use of Kenyan airports and pilots to channel weapons into Sudan has created serious political strain.

Support has not fully stopped, but the pressure is mounting. All the money the UAE pours into this war is likely to turn against them.

Recently, some UN agencies warned that Sudan risks collapsing under war, famine, and mass killings. What’s your take on that?

There are indeed actors who expect Sudan to collapse and who are waiting for it. Their biggest bet was famine.

But Sudan has not experienced famine throughout the war. In fact, grain production, though limited, doubled in 2024. What Sudan faces is not a shortage of food, but problems distributing it. After more than two and a half years of war, the state remains intact in its core institutions. Those betting on Sudan’s breakup are the ones actively working to make it happen—primarily by undermining the army.

Those who celebrated the fall of el-Fasher are the same groups supporting the project of partition. We place our hopes in our people, our allies, and the Sudanese army, and first and foremost in the determination of the Sudanese people.

The perpetrators of these massacres must be condemned and held accountable. The whole world has seen what happened—much of it filmed proudly by the militia itself. We saw civilians forced to dig their own graves before being executed for the simple act of trying to bring food to starving families.

Thousands were killed merely on suspicion—men, women, and children. Just today, more than 50 women and children were killed by a drone strike near el-Obeid. A children’s hospital in North Darfur was also targeted, and the young patients inside were killed by drone strikes operated by mercenaries brought in from various countries by the UAE to support the militia.

Which regional and global allies is the Sudanese army counting on right now?

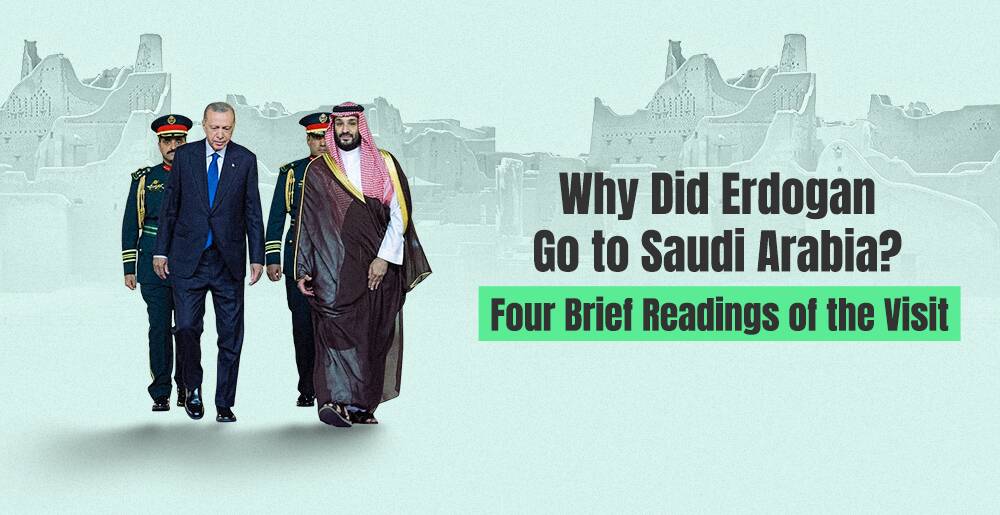

In the early months of the war, Sudan depended almost entirely on its own resources. But today, some allies have begun to recognize the scale of injustice inflicted on Sudan—the foreign-backed rebellion, the attempt to colonize the country through the RSF, the intimidation campaigns, and the systematic destruction of state institutions. Those who see this clearly have stood with Sudan. We are now looking with greater hope toward our Muslim partners, as President Erdogan recently indicated, toward our neighbors, and toward the free voices around the world who have stood on principle.

We know that many mercenaries from abroad, including Colombia, were brought in to support the militia. Yet even Colombia, on the opposite side of the world, has now taken positive positions out of moral responsibility. We hope for greater international support to expose the plot against Sudan.

This was never a civil war. From day one, it was a foreign intervention aiming to dismantle Sudan, destroy its institutions, and break the spirit of its people.

This has been clear throughout the war: when you target a country’s institutions, you’re not trying to protect it, you’re trying to destroy it. How can anyone claim to care about Sudan after that?

Add to that the killings, the terror, and the attempts to crush the will of Sudanese citizens.

We are facing the world’s largest displacement crisis, refugees and internally displaced people, yet Sudan receives barely 10% of its humanitarian needs. Far smaller crises elsewhere receive immediate global attention. Still, we believe that free nations and principled people will stand with Sudan, and we hope the world will pay closer attention to what is happening.

We expect many countries and civil societies to align with the Sudanese people and state. Recent days have already brought shifts in political positions worldwide, with growing calls to halt arms shipments to the militia and pressure the UAE and other sponsors of this war.

Billions of dollars are being spent monthly on flights bringing weapons to the militia in full view of the world, despite independent reports documenting the militia’s crimes and those enabling them. How can the world watch silently?

Britain’s obstruction is shameful. It called for a UN Security Council meeting, only to block measures that would have helped Sudan. Many British MPs and civil society voices are now pressing their government to change this disgraceful stance.

Some neighbors who once believed the militia could seize power are now reassessing the situation. We expect more shifts, and it is long overdue for Britain and others to rethink their position.

Do you see an Israeli hand in fueling Sudan’s war and deepening divisions?

Israel’s involvement in Sudan goes back decades. It supported the first southern rebellion, Anyanya, during Golda Meir’s era, and backed the second rebellion in 1983. It has long viewed Sudan as a hostile state: a supporter of Egypt and a supporter of the Palestinian Resistance.

Even when Sudan joined the 2012 Arab Peace Initiative, Israel still saw it as a country that needed to be weakened, especially because of Sudan’s strategic position on the Red Sea, its role in Egypt’s 1967 and 1973 wars, and the strong anti-injustice public sentiment in Sudan, including widespread solidarity with Palestinians. All of this drew Israel into Sudan long before today’s war.

Regarding the RSF and Israel, yes—there is cooperation. The militia’s leaders visited Israel and acquired surveillance systems during their post-2019 power-sharing period, which they later used to serve Israeli interests. Many of the militia’s weapons also came from Israel.

Israel’s strategic interest is fragmentation, breaking states apart. It has deep ties to what is happening in Sudan today, supporting the militia and facilitating its crimes. Even after the Sudanese Army chief agreed to join the Abraham Accords, massive public resistance made normalization politically impossible. That is why Israel is now trying to help dismantle the Sudanese state structure.

UN’s Role and the Road to Negotiations

What role should the UN and other international bodies play right now?

We need international bodies to classify the Rapid Support Forces as a terrorist organization, given the scale and nature of their crimes.

We also expect these organizations to scale up humanitarian assistance for refugees and displaced people. Unfortunately, we recently uncovered that a significant portion of aid entering through the Sudan-Chad corridor was actually weapons smuggled to the militia—a repeat of what happened in the 1980s during the so-called “Operation Lifeline Sudan” project, which ended up sustaining the southern rebellion.

Sudanese civilians have lost everything—homes, factories, businesses, and livelihoods. Millions of professionals have been forced to flee. Even museums and cultural sites have been looted, and tens of thousands of vehicles destroyed. We expect international and regional organizations, especially in the Islamic world, to support relief efforts, reconstruction, and recovery from the devastation caused by the UAE and other foreign backers of this war.

Do the recent developments in el-Fasher change the course of negotiations, and is the army likely to give any ground?

As for negotiations, remember that within the first month of the war the U.S. and Saudi Arabia hosted the Jeddah talks, where the RSF pledged to leave civilian facilities. They broke that promise immediately.

After the massacres we’ve witnessed, the Sudanese people cannot accept the RSF as a legitimate negotiating partner. Accountability must come first.

Given the atrocities in el-Fasher, any peace track is likely to freeze, not progress.

Weapons continue to reach the RSF from well-known sources. How can these supply lines be shut down?

Most of the weapons reaching the RSF are no secret. Much of the supply comes from the UAE, a fact clearly documented in international reports, yet the world continues to look away.

The arms flow through Libya under Haftar, through Chad, groups in South Sudan, Kenya, Uganda, Somaliland, and even parts of Europe, and American weapons have also appeared in the war. Everyone knows the routes and even the flight records are public. The problem is not a lack of information but a lack of global will to stop the pipeline.

We are confident that this war will end in victory for the Sudanese Army and the Sudanese people, and that those who ignited it will eventually pay the price. The Sudanese public and the free voices standing with them around the world remain unshaken despite the killings and abuses committed by this militia. The only way to end the continuous flow of weapons is for the international community to act, because it already knows exactly who is supplying them and how they are entering Sudan.