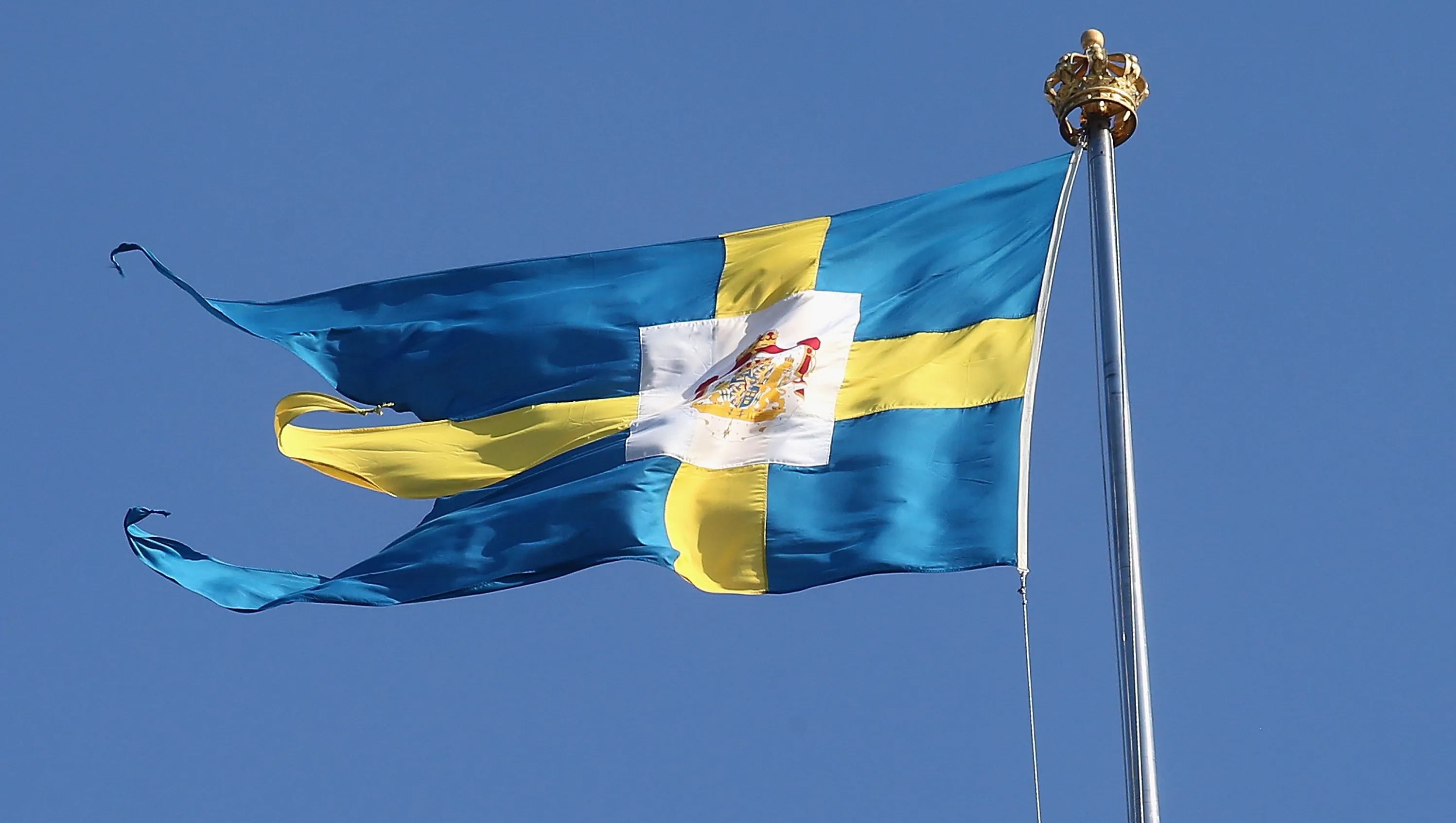

Did the New Swedish Rape Law Really Work?

In 2018, Sweden implemented a pivotal 'consent law' (samtyckeslagen), redefining the legal parameters of rape.

In the two years since Sweden enacted a landmark change in its sexual assault laws, the country has witnessed a 75 percent increase in rape convictions—a development lauded by rights advocates as a significant step forward. However, the progress remains incomplete.

In 2018, Sweden implemented a pivotal 'consent law' (samtyckeslagen), redefining the legal parameters of rape.

Under the previous legal framework, proving rape required evidence of threats, force, or the victim being in a particularly vulnerable state, such as being under the influence of drugs or alcohol.

The new legislation, however, mandates that both participants must actively signal consent, either verbally or through clear actions.

With the introduction of this law, Sweden became the tenth country in Western Europe to categorize all non-consensual sex as rape. Iceland adopted similar measures in the same year, followed by Greece in 2019.

Women’s Rights

This legislative shift was widely applauded by organizations championing women's rights and combating sexual violence, including Fatta, Unizon, and Amnesty International.

Olivia Björklund Dahlgren, a spokesperson for Fatta, a nonprofit focused on addressing sexual violence, said in media statements that the boundary between sex and assault is based on whether or not there's consent, so a law is needed that also regulates that.

This perspective is supported by a recent report from the National Council on Crime Prevention (Brå), which highlights the increase in both rape reports and convictions since the law's introduction.

Notably, many of these cases would not have been classified as rape under the previous legal standards.

In 2017, Sweden recorded 4,895 reported rapes, a figure that rose to 5,930 by 2019.

While this increase reflects a continuation of a long-term trend predating the 2018 legal reform, the impact of the new legislation is most evident in the sharp rise in rape convictions.

The number of rape convictions surged by 75 percent over two years, jumping from 190 in 2017 to 225 in 2018, and then to 333 in 2019, following the introduction of the consent law in July 2018.

Although many of these convictions still involved traditional factors such as force or threats, 76 cases fell under the new category, encompassing scenarios that previously would not have met the legal threshold for rape.

Stina Holmberg, a research advisor at the National Council on Crime Prevention (Brå), noted that the sharp uptick in rape convictions does not follow a similar long-term trend.

The new legal framework allows more cases of non-consensual sex to be prosecuted as rape, increasing the likelihood of conviction without needing to prove force, threats, or violence.

Holmberg highlighted that this includes cases where a victim clearly said 'no' or even cried, yet the perpetrator continued.

Such instances, along with cases where the victim was paralyzed by fear and unable to resist, would not have led to convictions under the previous law.

Long-Term Effect

Among 36 prosecutors interviewed by Brå, a majority—31—reported that the law had a positive impact, particularly in establishing that a failure to say 'no' does not imply consent.

Outside the courtroom, advocates believe the law has helped catalyze important conversations and set clearer societal boundaries. This may have encouraged more survivors to come forward and report their assaults.

The Swedish Association for Sexuality Education (RFSU) previously noted that the law facilitated discussions around consent, making it easier for individuals to define their experiences and either report them or seek support.

Nevertheless, legislation alone is insufficient to ensure more survivors report their assaults or to reduce the number of assaults.

When announcing the law, the Swedish government emphasized that "to effect real change, the legislation must gain traction throughout society."

In tandem with the legal changes, the Crime Victim Compensation and Support Authority received 5 million kronor to fund information and education campaigns on sexual offenses and consent, including an online course, social media initiatives, and a guide for teachers.

These efforts were welcomed by Amnesty International as a sign that the law was intended to be more than symbolic—it was also meant to drive substantive change.

However, the organization cautions that it will take time to see a reduction in sexual assaults.

Katarina Bergehed, Amnesty International's Senior Policy Adviser on Women's Rights in Sweden, said in media statements that the law is still relatively new, and it typically takes years to fully assess its impact.

Insignificant Reporting

Despite the legal reforms, only a small fraction of rapes in Sweden are reported to the police.

According to Brå, around 112,000 individuals in Sweden experienced rape or sexual assault in 2018, yet only 5,593 of these crimes were reported. Of the cases reported to police, just about seven percent proceeded to trial.

For a more significant impact, it is essential to examine and improve other parts of the system to ensure that survivors of rape receive adequate support and a fair chance at justice.

This includes enhancing the healthcare system, trauma care services, and police procedures.

Amnesty welcomed a police initiative announced last year to recruit new staff dedicated solely to investigating sexual crimes and domestic violence.

This move aims to strengthen the police's ability to prioritize these cases and conduct high-quality investigations. However, there is still considerable room for improvement, particularly in the type of trauma care available to victims.

Working with rape cases that involve no physical force or violence also presents inherent challenges. These cases require a different investigative approach and make evidence assessment more complex.

Brå consulted with police officers experienced in overseeing such cases, who reported that the 2018 law change has altered their work methods. One of the most significant changes has been the increased need for detailed questioning of those involved.

While some officers expressed concern that this level of detail might deter victims from reporting crimes due to the sensitive nature of the questions, others felt that it demonstrated the police’s commitment to taking these cases seriously.

In addition to broadening the definition of rape, the 2018 law introduced two new offenses: "negligent rape" and "negligent sexual abuse."

These categories address situations where consent was not established, yet the perpetrator did not intend to commit rape or assault.

However, in 2019, only 12 convictions were for negligent rape, a figure Holmberg attributed to the challenges of proving such cases.

Brå's report also suggests that, as this is a new law, courts may not yet fully understand when these offenses apply, leading to either acquittals or charges of rape instead of negligent rape.