Cash for Survival: How ‘Israel’ Destroyed Gaza's Financial System

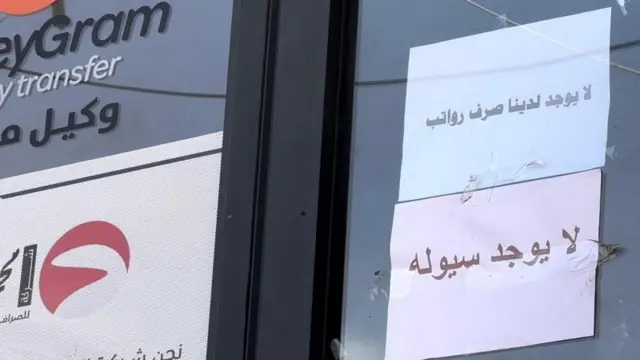

Salaries are not paid in full or on a regular basis, and banks are either closed or destroyed.

Amid relentless Israeli bombardment and a suffocating blockade, Gaza is grappling with a severe cash crisis and soaring fees on money transfers, threatening what remains of its shattered economy.

Since the start of the Israeli assault a year and a half ago, the crisis has evolved beyond collapsing infrastructure and shrinking incomes. The shortage of physical cash now directly affects daily life.

Salaries are not paid in full or regularly, banks are either shut down or destroyed, and financial transfers are either banned or heavily monitored, often with exorbitant fees.

This financial chokehold comes as the banking system crumbles, traditional funding dries up, and cash all but vanishes from the streets.

As a result, Gazans have resorted to primitive forms of barter, while aid organizations struggle with deepening financial paralysis.

Cash Crisis

Gaza’s financial system is in freefall. The population is now split across various salary-receiving groups: Former Gaza government employees receive partial payments labeled as “advances,” Ramallah government employees depend on bank transfers, while UNRWA staff and international organization workers are paid through special codes or digital systems.

But all face one problem: Cash is vanishing.

With banks shuttered or destroyed and ATMs out of service, salaries are either delayed, cut, or funneled through newly created local e-wallets born out of wartime necessity.

“We get a code from the agency, take it to a registered shop, and pay a 2% fee to convert it into money via the PalPay wallet,” said UNRWA employee Mohammed Hassan (32). Funds can then be transferred between the wallet and bank accounts, with each transaction incurring additional fees.

In place of cash, Gazans are now paying by transferring money from one e-wallet to another using phone numbers. Even the elderly, once hesitant to embrace digital finance, have adapted—driven by the sheer lack of alternatives.

“Cash has become almost impossible in Gaza,” Hassan told Al-Estiklal. “Everyone now uses digital wallets, and these platforms have established offices and agents.”

Raed Fares (40) calls the crisis “a different kind of war.” “Our daily struggle is simply finding money and figuring out how to pay, especially since many shops only accept cash,” he told Al-Estiklal.

Despite the spread of digital payments, cash remains essential for basics like taxis and market shopping; yet it’s nearly unobtainable. The banking system has collapsed, and currency is now both scarce and symbolic of survival.

With most banks closed, ATMs offline, and cash trading relegated to the black market, financial resources are distributed unfairly and unpredictably. Recently, another layer of hardship emerged: merchants began refusing older paper notes, particularly 20-shekel bills, having already stopped accepting the 10-shekel note.

After more than two months of sealed borders and the destruction or looting of financial institutions by “Israel,” no new currency is entering the local market. Gazans are left to trade what little paper money remains, a war within a war, fought over every shekel.

Heavy Commission Burden

In another challenge, Gazans trying to receive money from relatives abroad face steep commissions imposed by exchange offices and banks amid the financial collapse caused by the Israeli genocide.

Previously, money transfers were handled manually; someone abroad (e.g., in Turkiye) would hand over cash, and a local broker would deliver it in Gaza, with a commission of no more than 3%.

Today, the fee has skyrocketed to 35%, with no manual delivery options. Transfers must go through banks or complex and costly digital channels, according to the well-known Herzallah Exchange Office.

“Since the war began, I’ve paid over $3,000 in commissions; either from incoming transfers or just to get cash inside Gaza,” Fares, a local resident, told Al-Estiklal.

He explained that he often had to move money from one bank to another and then withdraw it in cash, a process that drained him financially due to high fees.

To avoid the commissions, Fares’ father sold his car for $3,000 below its market value because a buyer offered to pay in cash.

Many others are doing the same, selling valuable items at discounted prices just to get hold of cash, especially with no end to the war in sight and people increasingly detached from their physical assets.

With banks no longer functioning, cash traders—also known as money brokers—have become widespread in Gaza. They now serve as the only way to access money in these extreme conditions.

These traders buy cash from sellers at a 2% fee per 100 shekels (about $30), then resell it with commissions as high as 35% when converting from dollars to shekels or bank balance to cash.

They advertise their services anonymously on social media, offering cash conversions through banking apps and openly stating their high commission rates.

This phenomenon has intensified pressure on residents, who now have no choice but to rely on these methods amid the liquidity crisis.

In March 2024, Palestine Monetary Authority reported an unprecedented cash shortage in Gaza due to the Israeli destruction of bank branches and the shutdown of most ATMs.

It acknowledged receiving complaints about “extortion” by individuals, traders, and unlicensed exchange shops who use point-of-sale terminals or banking apps to extract up to 35% of transferred sums, delivering only the remainder in cash.

Alternatives and Solutions

In response to the crisis, Gazans have recently come up with alternative methods to ease the burden, most notably, bartering goods instead of relying on cash.

In August 2024, Ahmad al-Muqayyad launched a Facebook group titled “Gaza’s First Barter Market 2024,” aiming to create a platform for residents to trade items directly without the need for money.

The group has now grown to over 600 members, who regularly post and exchange goods to avoid high commission fees in the absence of cash.

“Looking for a chicken weighing no less than 2.5 kg in exchange for half a carton of eggs + 50 shekels (North Gaza – al-Saha),” one user posted.

“For small business owners: 8 sacks of flour available for trade in North Gaza,” another wrote. A third offered: “Small bicycle available for swap with a larger one suitable for a 12-year-old child.”

“Soon, we’ll be bartering low-value goods for other basic items. ‘You give me bread, I’ll give you falafel,’” Hussein quips in remarks to Al-Estiklal.

In response to traders rejecting worn or old banknotes, some young Gazans have launched a new initiative to restore and refurbish damaged currency.

Videos have circulated of youths setting up street stalls in Deir al-Balah to repair torn paper notes, offering these services for a small fee to keep the cash in circulation.

This economic deterioration is unfolding amid the total absence of Palestine Monetary Authority, which has offered no practical solutions, deepening the financial stagnation and suffering of civilians.

Faced with this reality, some Gazans believe alternatives must be found to avoid exploitation by greedy traders. Many see electronic payment as the most viable option for now.

In a Facebook post, Shadi Jabr wrote: “Did you know that digital banking in Gaza helps solve problems like the shortage of small denominations, the scarcity of 10-shekel notes, and the circulation of damaged or counterfeit currency?”

“But the greed of some traders who hoard cash to resell it on the black market is undermining this solution.”

“Once again, the humanitarian situation in Gaza is going from bad to worse. The scarcity of basic goods, soaring prices, and traders hoarding supplies, some even forming gangs to raid warehouses, alongside the ongoing cash crisis, all point to a looming large-scale famine,” Yahya Benrjab posted on X.

“What’s needed now is real financial support and backing for humanitarian initiatives in Gaza.”

“Those with an income struggle to obtain cash, while those without any income can’t afford the few goods available, which are limited to canned items,” said journalist Mohammed Haniya.