Egypt’s Parliamentary Elections: el-Sisi’s Clash With His Own Corruption Network

For the first time since taking power in 2014, Egypt’s head of the regime Abdel Fattah el-Sisi has twice stepped in to overturn a flawed law and annul rigged election results, despite having previously allowed numerous defective laws to pass and overseeing four manipulated elections for the House of Representatives and the Senate.

The first intervention came in September 2025, when el-Sisi objected to eight articles, out of 540, in the criminal procedure law, deeming them problematic and in need of revision.

Yet in a surprise move on 12 November 2025, he endorsed the law after parliament made only cosmetic amendments, despite objections from human rights groups that had condemned the entire legislation.

The second came on 17 November 2025, when he raised concerns about “substantial irregularities” in the results of the first phase of the 2026 parliamentary elections.

He called for the results in several constituencies to be annulled, culminating in the cancellation of elections in 27 percent of them, 19 out of 70 districts.

El-sisi’s decision to challenge provisions in the criminal procedure law, then approve it despite a lawyers’ boycott, and his objection to election fraud only to proceed with the vote and declare the pro-government list victorious even after reruns in 19 districts, all projected an image of a leader keen to uphold justice and electoral integrity.

But politicians and analysts argue that these limited interventions served a largely political purpose, to launder the reputation of controversial criminal legislation, widely criticized by human rights groups as repressive, and to pre-empt accusations of fraud against the next parliament.

They suggest that intervening in what is now the third parliamentary election since el-Sisi ousted Egypt’s democratically elected president, Mohamed Morsi, reflects his desire to avoid claims that the parliament expected to amend the constitution to “cement his rule indefinitely” was itself the product of electoral manipulation, and therefore “illegitimate.”

Yet, el-Sisi’s challenge to the election results inadvertently exposed his own judicial, security and media apparatus. The interior ministry had denied any fraud, the elections authority insisted there were no violations, the Judges Club disowned the entire process, and the confrontation put him at odds with state employees, including judges from the Administrative Prosecution Authority and the State Lawsuits Authority.

Reason for the Cancellation

Before the first phase of the parliamentary elections, many analysts, experts and politicians predicted that the January 2026 parliament would move to amend the constitution for a second time, the first being in 2019, with the aim of extending el-Sisi’s rule beyond its scheduled end in 2030.

It was already evident, through the careful engineering of the incoming chamber’s seats, that the next parliament was designed to include only those willing to cooperate in passing the government’s agenda. Its legislative and oversight functions were expected to be reduced to rubber-stamping almost anything the government wished to push through, in exactly the form it wanted, without any opposition.

The pro-government majority would therefore align seamlessly with the executive’s priorities, which appear to include exploring pathways to secure el-Sisi a fourth presidential term.

This was underscored by analysis from the Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy on October 21, 2025, which argued that the parliamentary elections would pave the way for a constitutional amendment extending el-Sisi’s tenure, or alternatively, prepare for a managed political transition after him.

Timothy E. Kaldas, a researcher at the Tahrir Institute, reinforced this view, saying that “Sisi needs a parliament he can fully control” in order to prolong his presidency, and that the elections were being engineered to produce a chamber tailored to the requirements of the coming phase.

This objective would have clashed sharply with any public perception that the next parliament was “fraudulent,” particularly as that accusation emerged not from opposition groups, which have been effectively sidelined, but from pro-government candidates themselves, many of whom spent heavily to secure seats. Their criticism proved awkward for the authorities.

El-sisi therefore intervened to demand reruns in the districts where his supporters had lodged complaints, or outright cancellations, allowing the elections to appear as though they had taken place in a democratic atmosphere.

The fact that voting was repeated in constituencies where appeals were filed would, in turn, help present the next parliament as “legitimate” and its decisions as “legitimate.”

More importantly, this would also cast a fresh constitutional amendment as “legitimate,” and portray any extension of el-Sisi’s rule as “legitimate,” leaving little room to accuse the parliament, as happened with the 2019 assembly, of colluding with the presidency to prolong his tenure, according to politicians and human rights advocates.

This time, el-sisi’s move to rerun elections in a quarter of all constituencies was not prompted by clashes between pro-government candidates and genuine opposition, but rather by the emergence of competing factions within the pro-Sisi camp itself, which posed a greater risk to the regime’s political calculations, according to the news site Mada Masr.

These loyalist factions “form the base the regime relies on for mobilization, something it may need if it decides to pursue a constitutional amendment allowing el-sisi to remain in office beyond his current term,” according to various political and judicial sources quoted by Mada Masr.

Four Slaps!

Although el-Sisi’s decision to annul the results in several constituencies was presented in a democratic light, the move appeared to deliver, implicitly, four blows to the security establishment, the judiciary, the media, and the pro-government parties aligned with him.

The first presidential slap, as observers described it, landed on the interior ministry. Just 24 hours before el-Sisi’s statement acknowledging electoral violations, the ministry had issued an enthusiastic announcement insisting there was no reason to question the integrity of the voting process, accusing the “terrorist Muslim Brotherhood” of spreading false rumors.

El-Sisi’s subsequent directive ordering an investigation into the reported abuses, based on complaints he said he had received, and his call on the National Elections Authority to reveal the facts, made the presidential statement appear humiliating for the interior ministry and dismissive of its political grandstanding, according to journalist Gamal Sultan.

The second slap, as critics framed it, was directed at the National Elections Authority. The body had failed to respond to the various allegations of fraud, repeating the same stock assurances about the integrity of the vote.

El-Sisi’s own challenge to the results effectively undercut its credibility, to the point that some politicians called for the resignation of the judges overseeing the authority.

The head of the National Elections Authority was then forced to acknowledge the existence of appeals in 88 constituencies across 14 governorates, and to announce a decision to rerun elections in districts where violations were confirmed, a total of 19 out of 70 constituencies, amounting to 27 percent of all contested seats.

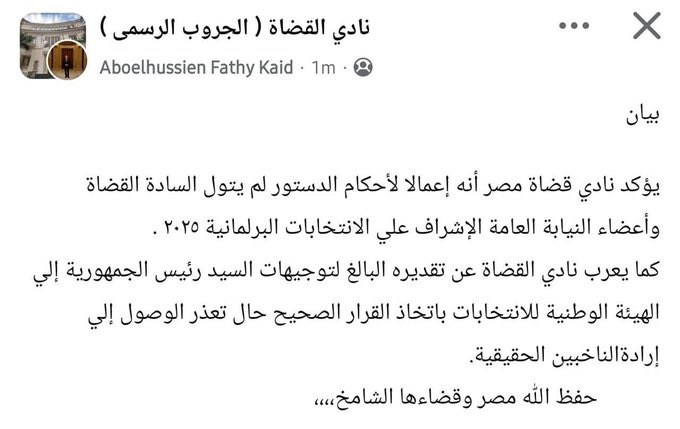

After Egyptians accused the “elections authority judges” of participating in fraud, an unexpected twist followed when the Judges Club of Egypt publicly distanced itself from the rigging of the parliamentary elections, after voting was annulled in a quarter of all constituencies. The club insisted that “judges and public prosecutors did not supervise the elections.”

The Judges Club affirmed that judges and members of the public prosecution did not oversee the 2025 parliamentary vote in accordance with constitutional provisions, an implicit reference to the fact that the process had instead been supervised by government-appointed jurists from the State Lawsuits Authority and the Administrative Prosecution Authority.

The statement implicitly suggested that those involved in the fraud were not independent judges, but “government employees,” namely members of the State Lawsuits Authority and the Administrative Prosecution Authority, who are appointed by the executive.

The 2014 constitution abolished full judicial supervision of elections, but introduced a transitional period of ten years, ending in 2024, during which judges would continue to oversee voting before the process shifted entirely to the National Elections Authority, on the grounds of creating an independent body with civil society oversight.

In practice, the National Elections Authority, like other judicial bodies in Egypt, has shifted from an autonomous institution to one staffed by officials appointed by el-Sisi, and its role has evolved from neutral oversight to acting as a state body that ratifies results in line with the wishes of the authorities.

Given the significance of the Judges Club’s statement, its authors concluded by expressing strong appreciation for el-Sisi’s directives to the National Elections Authority, instructing it to take the “correct decision” if it became impossible to identify the voters’ true will, describing his guidance as “reflecting the state’s commitment to integrity and transparency.”

The third slap landed on the pro-government media, which had loudly praised the integrity of the vote before Sisi’s intervention forced many of its leading voices to reverse course.

The fourth came from the associations representing members of the Administrative Prosecution Authority, which effectively overturned the narrative by implicitly confirming that their members had simply carried out orders, namely, engineering and falsifying results in favor of specific candidates.

In a statement posted on his official Facebook page, el-Sisi referred to “incidents” and “violations” that had taken place in several constituencies during the first phase of the parliamentary elections.

He called on the National Elections Authority to examine the complaints thoroughly, even if that meant annulling the entire first phase of voting.

El-Sisi wrote, “I have been informed of the incidents that took place in some constituencies where individual candidates competed. These incidents fall under the exclusive jurisdiction of the National Elections Authority to review and rule on, as the authority is independent in its work in accordance with its founding law.”

He urged the authority not to hesitate “in taking the correct decision if it becomes impossible to determine the voters’ true will, whether by fully canceling this phase of the elections, or partially canceling it in one or more constituencies,” and to rerun the vote where necessary.

Dr. Amr Hashem Rabie, deputy director of the Ahram Center for Strategic and Political Studies, emphasized that the management of the electoral process “clearly exposes the National Elections Authority’s loss of independence,” adding that “if there were any sense of responsibility, it would have resigned immediately.”

Speaking to the site Third Angle on November 17, 2025, Rabie said that the emerging facts reveal “a weak authority, subject to directives,” participating, whether actively or passively, in undermining the electoral process.

This, he said, occurs “through placing specific names at the top of candidate lists, turning a blind eye to the selling of seats, allowing near-hereditary passage of substitute seats, or permitting candidates to switch constituencies without any professional or legal standard.”

He described the “deliberate exclusion of a number of opposition candidates” as part of the same pattern, deepening doubts over the integrity of the electoral landscape as a whole.

Rabie also criticized the harm to the image of the state, “by organizing elections in which almost half the seats are effectively uncontested, which empties the political process of meaning and produces a purely formal electoral scene that does not reflect the true will of the voters.”

He noted that the current trajectory reflects “a desire to push things through as they are, in a manner that makes the process appear orderly on the surface, while simultaneously diluting its substance and stripping it of meaning.”

The first phase of voting witnessed a number of crises captured on video and shared on social media. Among them, former MP Nashwi al-Deeb withdrew from the Imbaba constituency just an hour after polling opened, in protest at the “absence of integrity and transparency, and the preallocation of seats to a security-backed candidate.”

Another crisis occurred in the el-Montazah district of Alexandria, when Ahmed Fathy Abdel Karim, a candidate from the Reform and Renaissance Party, appealed directly to el-Sisi after discovering that several ballot boxes within a polling station had been opened, suggesting evidence of fraud.

Candidate Mahmoud Gwelly also appealed directly to el-Sisi, claiming that he had been approached with offers of money within the Fifth Settlement constituency in an attempt to influence his stance in the upcoming parliamentary elections.

He was briefly arrested before being released.

Is the New Parliament Legitimate?

Despite the authorities’ attempts to prevent popular, and then judicial, challenges to the integrity of the parliamentary elections, and by extension the “legitimacy” of the 2026 parliament, and any resulting challenge to el-Sisi’s rule should the deputies extend his presidency through a constitutional amendment, questions over legitimacy remained unresolved.

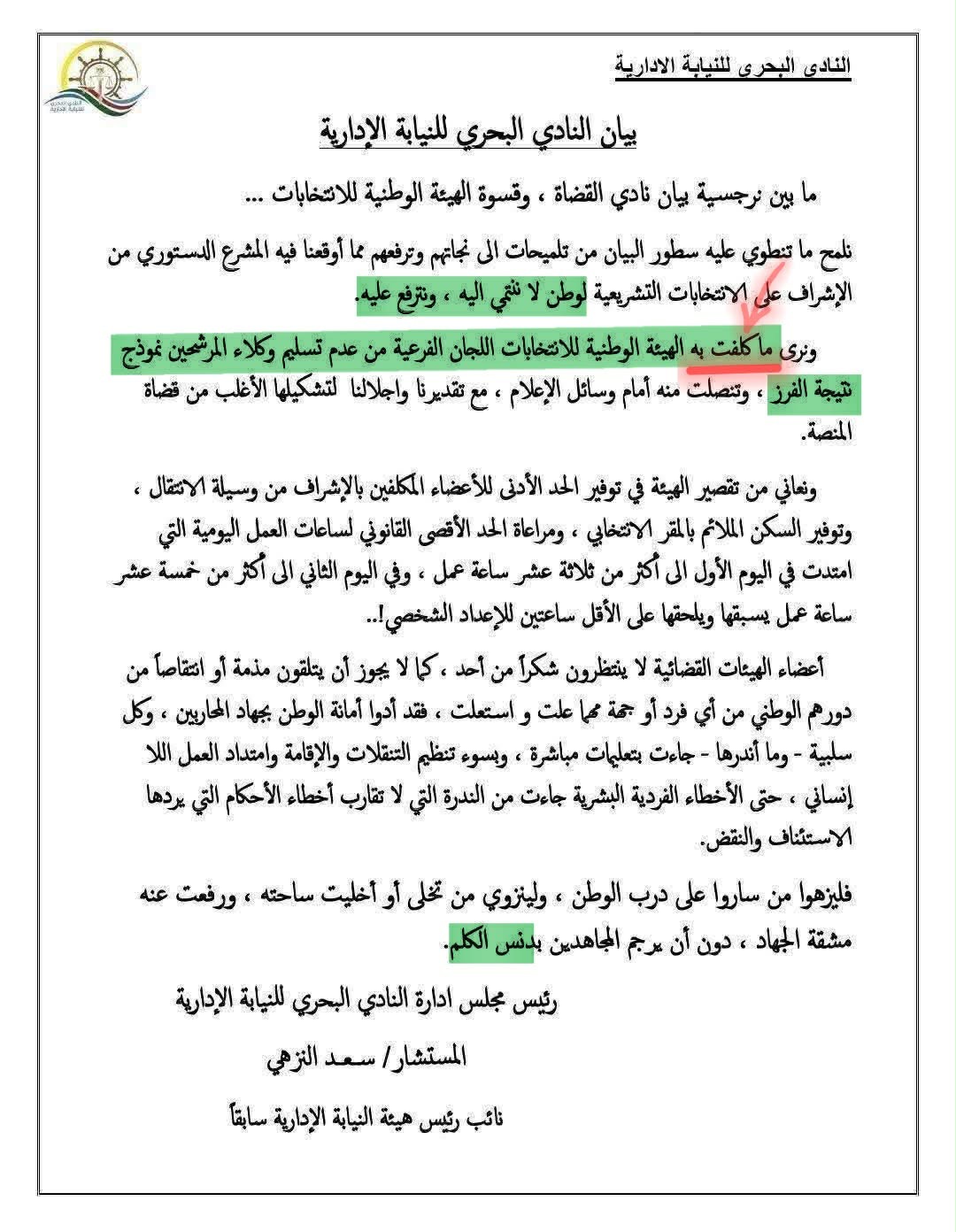

The conflict that erupted between judicial bodies, including the Judges Club, the State Lawsuits Authority, the Administrative Prosecution Advisors Club, and the Maritime Administrative Prosecution Club, along with a war of judicial statements, implicitly answered the question of legitimacy with stark clarity.

The battle of statements between the judicial bodies and the National Elections Authority exposed what had been “stolen”: the will of the people. It confirmed that no genuine elections had taken place.

In response to the Judges Club statement, which asserted that judges and public prosecutors had not supervised the elections, the Administrative Prosecution Club acknowledged that the elections authority appointed by el-Sisi was responsible for rigging the vote, including revealing phrases such as that the authority had been “tasked” not to deliver the results of the counting, clearly signalling intentions to manipulate outcomes.

Lawyers and human rights advocates noted that the Administrative Prosecution statement indicated the crisis went far beyond a mere institutional dispute, exposing a complete collapse in judicial oversight of the parliamentary elections, voiced by those who had actually administered them this time as part of a pro-government apparatus.

They explained that there is a distinction between a “judge” sitting on a courtroom bench, and the reality that became apparent to all: the so-called “institutional judges” who supervised the elections were subordinated to the executive, not independent.

These included officials from the State Lawsuits Authority and the Administrative Prosecution Authority. Accordingly, the Administrative Prosecution statement admitted that they were “tasked” with withholding the results from candidates, meaning the vote was effectively rigged.

“This statement signifies that the Administrative Prosecution has disclaimed any responsibility for electoral integrity, placing direct accountability on the National Elections Authority as the constitutionally mandated body managing the process,” a human rights lawyer told Al-Estiklal.

He emphasized that this effectively undermines the entire election, not just the partial reruns announced by the National Elections Authority in some constituencies, because the issue concerns the integrity and impartiality of the administration of the election, which he said was entirely compromised.

He added that this opens both legal and political avenues for broad challenges to the results, potentially invalidating the incoming parliament even if some reruns are conducted, and, more importantly, that “the legitimacy of the parliament is now at stake.”

Journalist Amr Badr, a former member of the Journalists’ Syndicate Council, described the situation as strange and incomprehensible, noting that the authority had annulled elections in 19 single-member constituencies while simultaneously declaring the pro-government list victorious in the same districts where violations had led to annulments.

Badr argued that the solution lies in canceling the elections entirely, reconsidering the electoral system, reforming the laws, abandoning the failed absolute list system, creating conditions for genuinely competitive elections, opening public space, and lifting restrictions on politics and the media.

Former presidential candidate and lawyer Khaled Ali highlighted the most alarming aspect of the statement from the Maritime Administrative Prosecution Club, pointing to the line regarding the tallying of votes, namely, orders given to the elections committee not to provide candidates with copies of the official count results.

He noted that the statement exposes “the degree of trustworthiness, honesty, and competence of those who publicly oversaw the elections versus those who actually managed them behind the scenes.”

Despite el-Sisi’s move to order reruns in some constituencies, which embarrassed the interior ministry, election judges, and pro-government media, even figures close to the regime, including lawyer and TV presenter Khaled Abu Bakr, acknowledged the wider legitimacy crisis.

Khaled Abu Bakr, host of Akhir Al-Nahar on Al-Nahar TV, said that the annulments represented “a very serious crisis,” leaving the next parliament in a state of “difficult birth,” and the most pressing question being: will this birth be legitimate?

He stressed that “the legitimacy of the upcoming House of Representatives will now depend on the public’s assessment,” adding that “electoral legitimacy is now on the line.”

The resignation of three members of the al-Arjani Party (National Front), which is being groomed to inherit the Nation’s Future Party Mostaqbal Watan, over the alleged electoral fraud and challenges to the validity of the parliamentary vote, implicitly underscored a deepening legitimacy crisis recognized by all.

Before the scandal over fraud erupted and widened, reports circulated about a “secret security report” warning of an unplanned, unorganized popular uprising, which reportedly alarmed el-Sisi and prompted him to post a call for an investigation into alleged rigging in several constituencies.

The so-called “sovereign report,” cited by the site Third Angle, drawing on two sources, reportedly warned el-Sisi of public anger over widespread fraud, a concern to which he responded through his official social media accounts.

According to the sources, the confidential reports carefully documented potential popular reactions to the violations and stressed the importance of intervention to address the matter.

Ironically, Ahmed Bandery, executive director of the National Elections Authority, stated that “it is not reasonable to annul 19 constituencies in just six hours following the president’s statement,” according to al-Chourouk on November 20, 2025.

“These decisions were already made based on independent and complete procedural work […] the president’s statement gave the authority reassurance and strengthened its position,” Bandery added.

Sources

- El-Sisi’s interventions exposed election rigging and judicial complicity while attempting to portray his parliament and rule as legitimate.

- 2025 Elections… What Comes After the President’s Earthquake? [Arabic]

- “A Seat in the Elections Club”… The Road to the President’s Statement [Arabic]

- “Judges Club”: Judges and Public Prosecutors Did Not Supervise the Elections [Arabic]

- Battle of Authority… Judicial Statements Clash Over Responsibility for Election Manipulation [Arabic]