Through al-Habtoor Attack: What Message Is the UAE Sending to Egypt’s Sisi?

The UAE's move seems aimed at turning up the heat on Egypt, as tensions simmer over the Libya and Sudan files.

In an unexpected twist, Egypt’s cabinet publicly denied claims made by Emirati businessman Khalaf al-Habtoor, who had accused Prime Minister Mostafa Madbouly of tripling the price of a North Coast property from $10 million to $30 million. Shortly after, al-Habtoor backtracked and praised the Egyptian government’s transparency—an apparent attempt by both sides to paper over an obvious trust gap.

The fallout from al-Habtoor’s remarks came just as he revealed he had repeatedly advised head of the Egyptian regime Abdel Fattah el-Sisi not to take on foreign loans that would leave Egypt beholden to international institutions—advice Sisi clearly chose to ignore.

The timing coincided with a noticeable cooling in relations between Cairo and Abu Dhabi, driven by growing tensions over Libya and Sudan, raising questions about deeper political rifts.

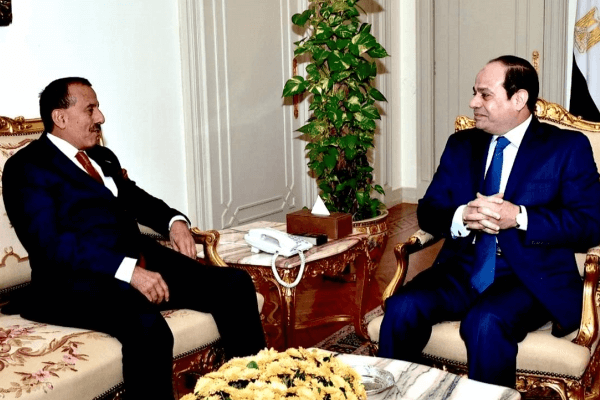

Despite enjoying generous access and red-carpet treatment in Egypt, al-Habtoor has failed to follow through on any of his promised investments since 2015—even after multiple personal meetings with el-Sisi, sources familiar with the matter told Al-Estiklal.

Since his first meeting with the head of the regime, the Dubai-based al-Habtoor Group has repeatedly announced plans for major projects in Egypt. Yet, none have materialized. Each time he floated grand promises of transformative investments, they quietly vanished—without a single dollar committed.

Instead of launching financial ventures, al-Habtoor raised eyebrows by opening a politically tinged research center, sparking speculation over its purpose—why would a businessman build a think tank instead of actual businesses, especially one known as a vocal advocate of normalization with the Israeli Occupation?

Often dubbed “the king of alcohol” and a staunch proponent of normalization, al-Habtoor is seen as a key figure in UAE-”Israel” ties and a loyal operative of Mohammed bin Zayed’s regional strategy.

He previously claimed interest in investing in Lebanon as well—but instead of launching economic projects, he founded a TV station in early May 2024, under the banner of “spreading happiness and entertainment.” It was later revealed to be a normalization platform. Hezbollah blocked the initiative, prompting al-Habtoor to scrap the project and accuse the Lebanese government of being hostile to investors before pulling some of his assets from the country.

Why Did They Turn on Him?

The fallout between Emirati businessman Khalaf al-Habtoor and the Sisi regime didn’t just shed light on who really controls wealth in Egypt—it also hinted at possible political rifts between Cairo and Abu Dhabi. The controversy even sparked speculation about behind-the-scenes “brokerage” in state land deals.

The tension erupted after al-Habtoor claimed in a July 7, 2025 interview with CNN Business that the Egyptian government had tripled the asking price of a North Coast plot he was interested in. He said the initial offer was $10 million, but that the price suddenly jumped to $30 million—allegedly after Prime Minister Mostafa Madbouly personally intervened.

Three days after his remarks, on July 10, the Egyptian government issued a statement flatly denying al-Habtoor’s claims. It asserted that no official request had ever been submitted by the Emirati businessman to purchase land in the North Coast area—raising the obvious question: how could Prime Minister Madbouly have intervened in a deal that never existed?

That same day, al-Habtoor made a sudden U-turn. He praised the government’s response and suggested the land price story had been a misunderstanding. He went on to applaud Egypt as a “country of institutions” that promotes transparency and a fair investment climate.

But al-Habtoor’s initial frustration over a real estate deal seemed to carry political undertones. In his CNN interview, he took subtle jabs at el-Sisi, recalling how he had personally advised him: “Don’t borrow from the IMF—these loans will enslave you.”

He also referenced high-value plots owned by the government and military, claiming he had offered to buy state-owned land in Cairo’s Salah Salem district and other military-controlled areas—subjects usually off-limits in Egypt’s political discourse.

According to Egyptian analysts, his comments echoed a broader Gulf sentiment—shared by Saudi Arabia—that criticizes Sisi’s reliance on foreign loans without delivering meaningful investments, fueling poverty and instability that could ripple into the Gulf.

They suggest that al-Habtoor’s remarks were not offhand, but part of a calculated message from Abu Dhabi—a quiet expression of frustration over Cairo’s economic trajectory. That message may have triggered Egypt’s sharp public response.

Egypt’s external debt rose by $1.6 billion in the first quarter of 2025, reaching $156.7 billion, up from $155.1 billion at the end of 2024, according to the Ministry of Planning.

And on July 7, the Central Bank revealed that Egypt faces $40.7 billion in external obligations coming due in the 12 months starting May 2025—including $37.3 billion in loans, $1.9 billion in repo-related payments, and $1.3 billion in open FX positions.

The Emirati message also appears to be a form of pressure on Cairo, amid mounting disagreements over Libya and Sudan.

Egypt accuses the UAE of backing attacks by the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), led by Abdelrahim Dagalo (brother of Hemetti), on the sensitive border triangle between Egypt, Sudan, and Libya. Cairo believes Abu Dhabi encouraged its ally in eastern Libya, Khalifa Haftar, to support Hemedti’s forces with fighters and weapons.

Egypt had previously warned the RSF against deploying armored vehicles and drones to the border zone, and reports emerged of a joint Egyptian-Sudanese airstrike on RSF fighters backed by Haftar’s mercenaries.

Diplomatic sources told Al-Estiklal that this border crisis was the primary reason head of the Egyptian regime Abdel Fattah el-Sisi summoned Haftar for a meeting on June 30, 2025. During the meeting, Sisi is said to have delivered a clear message: stop arming Hemedti’s militia or sending reinforcements.

Khartoum had recently exposed RSF incursions into the triangle with Haftar’s backing—territorial gains that were later rolled back under Egyptian military pressure.

Tensions between Sisi and Gulf leaders have become increasingly visible. Online criticism from Gulf influencers has surged, and relations between Sisi and both Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman and Emirati ruler Mohammed bin Zayed appear to be fraying—largely over Abu Dhabi’s continued support for Hemedti, which Cairo views as a threat.

Some analysts see these developments as part of a broader message—perhaps even a warning—from regional and international powers, including Washington: that Sisi has become a burden on Egypt and the region. The fear, they say, is that a popular uprising in Egypt could erupt, destabilizing Gulf interests and threatening Western and Israeli Occupation security calculations.

In response, Sisi’s loyal media figures and security officials have ramped up rhetoric about a “conspiracy” targeting “the president” and the Egyptian state—echoed by pro-regime voices like journalist and MP Mostafa Bakry.

Al-Habtoor Research Center

Though Khalaf al-Habtoor is primarily known as a businessman with interests in real estate and the automotive industry—and despite never launching a single project in Egypt—he established al-Habtoor Research Center, a think tank publishing strategic assessments and periodicals in fields far removed from his core business activities.

The center’s purpose remains vague. Its self-description focuses largely on promoting al-Habtoor’s global business ventures—hotels, real estate, and car dealerships—without offering a clear explanation of the center’s mission.

So far, the center’s research hasn’t provided any groundbreaking insights. Much of its focus is on Iran’s nuclear future and Western policy, while steering clear of more sensitive topics where the UAE is directly involved, such as Sudan, Egypt, or Libya.

The center has drawn questions for its opaque goals and affiliations. Among its board of trustees are two vocal critics of Egypt’s 2011 revolution: academic Mostafa el-Feky and media figure Abdel Latif el-Menawy. Rumors also circulated that journalist Ibrahim Eissa had been given a key role at the center, though this has not been officially confirmed.

Following public criticism of al-Habtoor, el-Feky released a statement distancing himself from the center, saying he played no active role in its operations and only attended an annual gathering with a broader group of intellectuals, officials, and media personalities.

The center’s board of trustees also includes Lebanese academic Ahmad Dallal, President of the American University in Cairo (AUC), who came under fire for allowing security forces to suppress student protests on campus against the Israeli genocide on Gaza.

According to journalist Hafez al-Mirazi, Dallal stood by as authorities handled students, faculty, and even administrative appointments, treating AUC no differently than state-run Egyptian universities. Once a supporter of academic boycotts, Dallal appears to have abandoned that stance by joining a center run by a staunch supporter of “Israel.”

Egyptian researchers have questioned why a real estate tycoon like Khalaf al-Habtoor would establish a political, economic, and social research center in Egypt—and why his company is recruiting Egyptian researchers to serve its goals.

“What is the true purpose of this center? What benefit do we stand to gain from its creation, especially when we already have dozens, even hundreds, of similar institutions?” asked former Egyptian ambassador Mohamed Morsy.

“Who will ultimately receive the information gathered so freely and officially about Egypt? And how will that information be used?”

Egyptian journalist Manal Ahmed also questioned why a businessman whose main investments and ventures are in real estate would establish a political and security research center in the capital of another country instead of his own.

“On what basis do Egyptian journalists and researchers engage with him? What kind of research does the center produce, and who is it intended for?”

Ahmed pointed out that while Britain blocked the UAE from buying the Telegraph newspaper or increasing its stake in Vodafone over national security concerns, Egypt allowed al-Habtoor to open a UAE-backed political and security research center with an unclear purpose.

Egyptian activist Sameh Abou Arayes questioned the motives behind al-Habtoor’s activities in Egypt, calling him “a very suspicious figure” who “opened an office for his company in Tel Aviv,” established a political and social research center in Egypt, and attempted to acquire land belonging to the Military Academy. He challenged al-Habtoor with the question: “Who do you represent?”

At the center’s inauguration in Cairo, al-Habtoor claimed it “will serve as a hub to support Arab youth, governments, and decision-makers by leveraging the research and studies produced here, while also providing opportunities to train and qualify a new generation of researchers.”

A statement from the center said it aims to support policymakers, raise awareness, and promote open public dialogue on Middle Eastern and global issues alike.

Sources

- Al-Habtoor expresses Egypt interest

- Al-Habtoor Research Center: Aiming to Craft Solutions and Contribute to Crisis Management [Arabic]

- From a “Fabricated Incident” to an Official Thank You: The Full Story of Emirati Businessman Khalaf al-Habtoor’s Dispute with the Egyptian Regime [Arabic]

- Khalaf al-Habtoor Meets with Sisi, Calls for Creating Incentives for Investors [Arabic]