Protests in Akhannouch’s Stronghold Raise Questions Over His Political Future

“Moroccans have been “burned by Akhannouch’s poor governance like never before.”

Two weeks of public unrest over failing health and social services boiled over in Agadir on Sunday, September 14, 2025, putting Prime Minister Aziz Akhannouch’s administration under intense scrutiny.

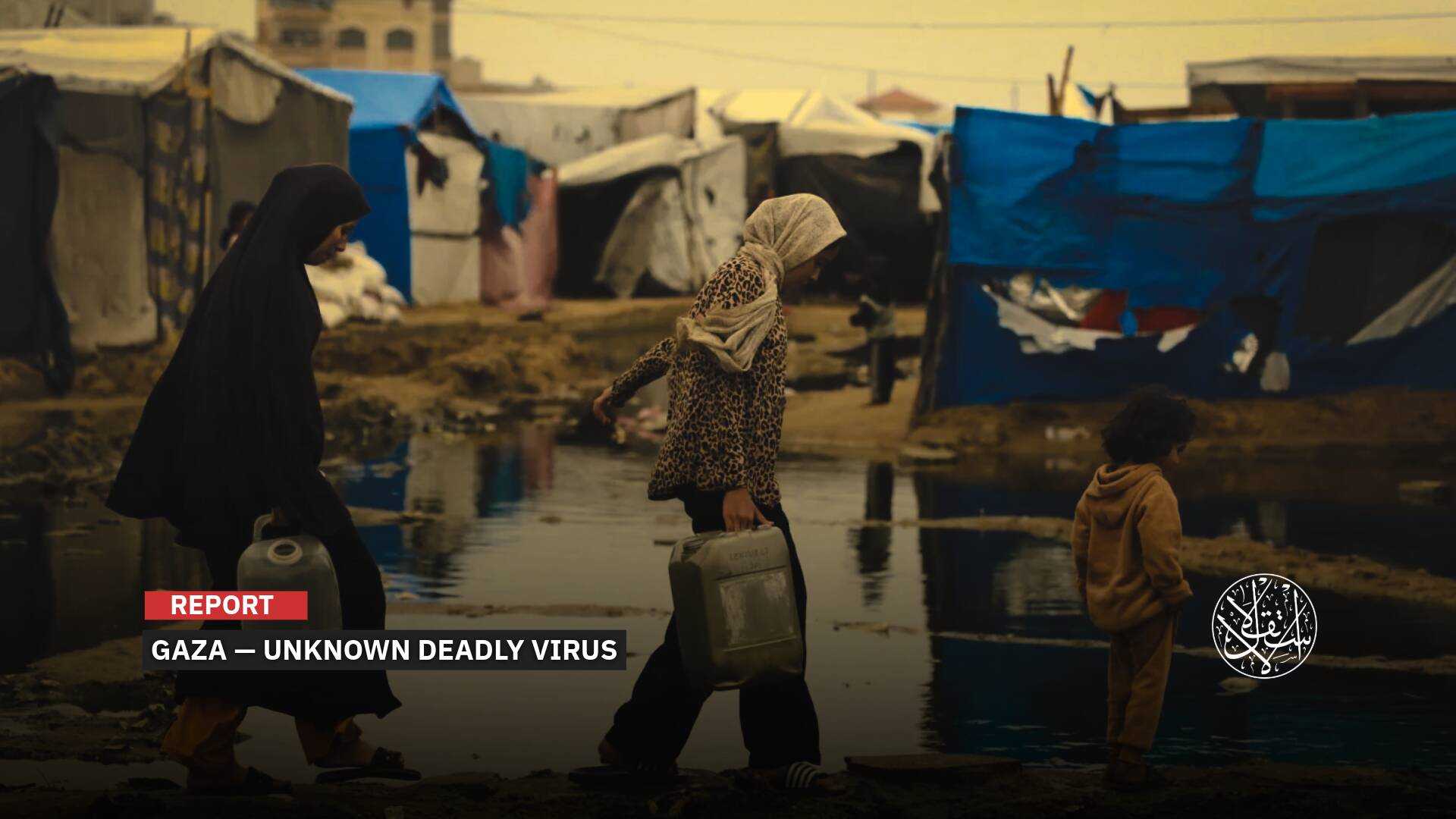

Hundreds gathered outside Hassan II Regional Hospital, dubbed the “hospital of death,” to protest rising unexplained deaths, collapsing services, and a lack of basic equipment.

Protesters chanted slogans including “The people want to end corruption” and “Is this a hospital or a graveyard?” while demanding more medical staff and vital supplies amid mounting deaths among pregnant women.

The demonstrations drew a heavy security presence, with auxiliary forces deployed to disperse the crowds. Anger targeted not only the health minister but also Akhannouch, who days earlier had appeared on state television lauding “unprecedented achievements” and insisting Moroccans were satisfied with his government’s performance.

For weeks, activists had been warning of a wave of deaths at Hassan II Hospital in Agadir, alongside a steady decline in basic medical services. The Moroccan Network for Human Rights and the Defense of Territorial Integrity said the hospital, which serves not only the Souss-Massa region but also the three southern provinces, is operating far beyond its capacity. The group urged the government to urgently improve care, add staff and equipment, and launch a transparent judicial probe into the rising number of maternal deaths.

Voices of Public Outrage

Parliamentarian Naima el-Fathaoui of the opposition Justice and Development Party called Sunday’s rally “a real outcry” against the collapse of health care at the region’s largest hospital. Speaking to Al-Estiklal, she said demonstrators were protesting both the government’s mismanagement of the sector and the grim reality of a hospital now branded “the hospital of death.”

El-Fathaoui dismissed the recent replacement of the hospital director as cosmetic, arguing the system requires deep structural reform. She said the crisis places Prime Minister Aziz Akhannouch in a particularly awkward position, given that he not only leads the national government but also chairs Agadir’s municipal council—a role he has neglected, she noted, by skipping 35 council sessions, “a world record.”

The lawmaker also ridiculed Akhannouch’s September 10 television interview, in which he described Morocco’s health sector as undergoing a “historic transformation.” Ordinary citizens, she said, can hardly take such claims seriously when they lack access to the most basic services available in hospitals worldwide. The government’s promises of universal health coverage and social support programs, she added, ring hollow to a public that “knows better than to believe false dreams.”

Her criticism was echoed by Halima Chouika, deputy secretary-general of the National Labor Union of Morocco, who described the protests as a direct blow to the prime minister. Agadir, she argued, is not Akhannouch’s electoral base at all. “His real stronghold is rentier privilege, corruption, and conflicts of interest, backed by state support,” she said.

Chouika contended that Akhannouch would never have risen to head either the city or the government in a genuinely transparent political system. The latest protests, she concluded, were fueled by his “hollow and misleading” television appearance, which exposed what she called his failed stewardship of both Agadir and the country’s health sector. To many citizens, she added, Akhannouch is neither a credible politician nor even a real businessman, since his success has been built not on merit but on privilege and influence.

Widespread Reaction

In response to the protests, Isaac Charia, secretary-general of the Moroccan Liberal Party, said residents of Agadir know better than anyone the true character of the prime minister, who also serves as their mayor. That, he argued, is why they poured into the streets after his televised appearance, claiming that Moroccans were pleased with his government and its development projects, especially in health.

In a Facebook post on September 15, 2025, Sharia said the massive protests in Agadir show beyond doubt that the sun of government failure is too big to be covered by the sieve of media appearances and influencer propaganda.

He added that health coverage and direct social support programs, once promoted as royal projects, had been warped by conflicts of interest and corruption, turning into sources of tension and unrest rather than instruments of protection and stability for citizens.

Former lawmaker and journalist Rihhab Hanane of the Socialist Union warned that the uproar was not confined to Agadir, cautioning it could spread to hospitals nationwide.

In a Facebook post, Hanane said what happened in Agadir—protests against the collapse of public health services, the greed of much of the private sector, and corruption across the system at local and regional levels—could snowball into something much larger.

From the banned Islamist movement al-Adl wal Ihssane, senior figure Hassan Bennajeh echoed the protesters’ chant in Agadir, saying, “Where did the health funds go? To Mawazine and the concerts.”

In another Facebook post, he added that nothing illustrates the decay of Morocco’s health system more clearly than officials themselves, who rush abroad for treatment at the slightest ailment.

Journalist Abdellah Tourabi criticized Prime Minister Aziz Akhannouch for appointing a health minister unfit to manage such a complex portfolio.

In a Facebook post on September 15, 2025, Tourabi argued that the problem was not Amine Tahraoui himself but the man who put him forward. Akhannouch, he said, had chosen a young and inexperienced loyalist, both technically and politically, to run a ministry that even seasoned figures such as former ministers el-Hossein el-Ouardi and Khalid Ait Taleb had struggled to control.

According to Tourabi, the appointment reflected Akhannouch’s preference for personal loyalty over competence, choosing aides from his inner circle rather than qualified ministers.

In a September 15 article, Assahifa described the massive protests in Agadir as “highly embarrassing for the prime minister.”

The paper criticized the Health Ministry’s move to remove the hospital director and leave the post vacant as “a partial administrative fix,” falling short of the deep reforms the public is demanding.

Parliamentary Response

Several Moroccan lawmakers have reacted to the Agadir protests, both from the majority and the opposition. Khalid Chennak of the ruling Istiqlal Unity and Justice group submitted a written question to Health Minister Amine Tahraoui regarding the hospital’s alarming conditions.

Opposition parliamentarian Fatima Tamni of the Democratic Left Federation also submitted a written question to the minister, denouncing “the catastrophic situation at Hassan II Hospital in Agadir and citizens’ protests over deteriorating health services.”

According to TelQuel on September 15, 2025, Tamni said the hospital suffers shortages across the board, including essential medical and logistical supplies such as IV solutions, test tubes, antibiotics, and medical gloves.

She added that a severe lack of patient carriers and transport equipment forces some transfers between departments to pass through the street, compromising patient dignity and safety. The facility also lacks basic amenities, including enough toilets for staff and patients, rest areas, and food provision during night shifts. Sanitation conditions are alarming, with stray cats roaming corridors, rooms, and even beds.

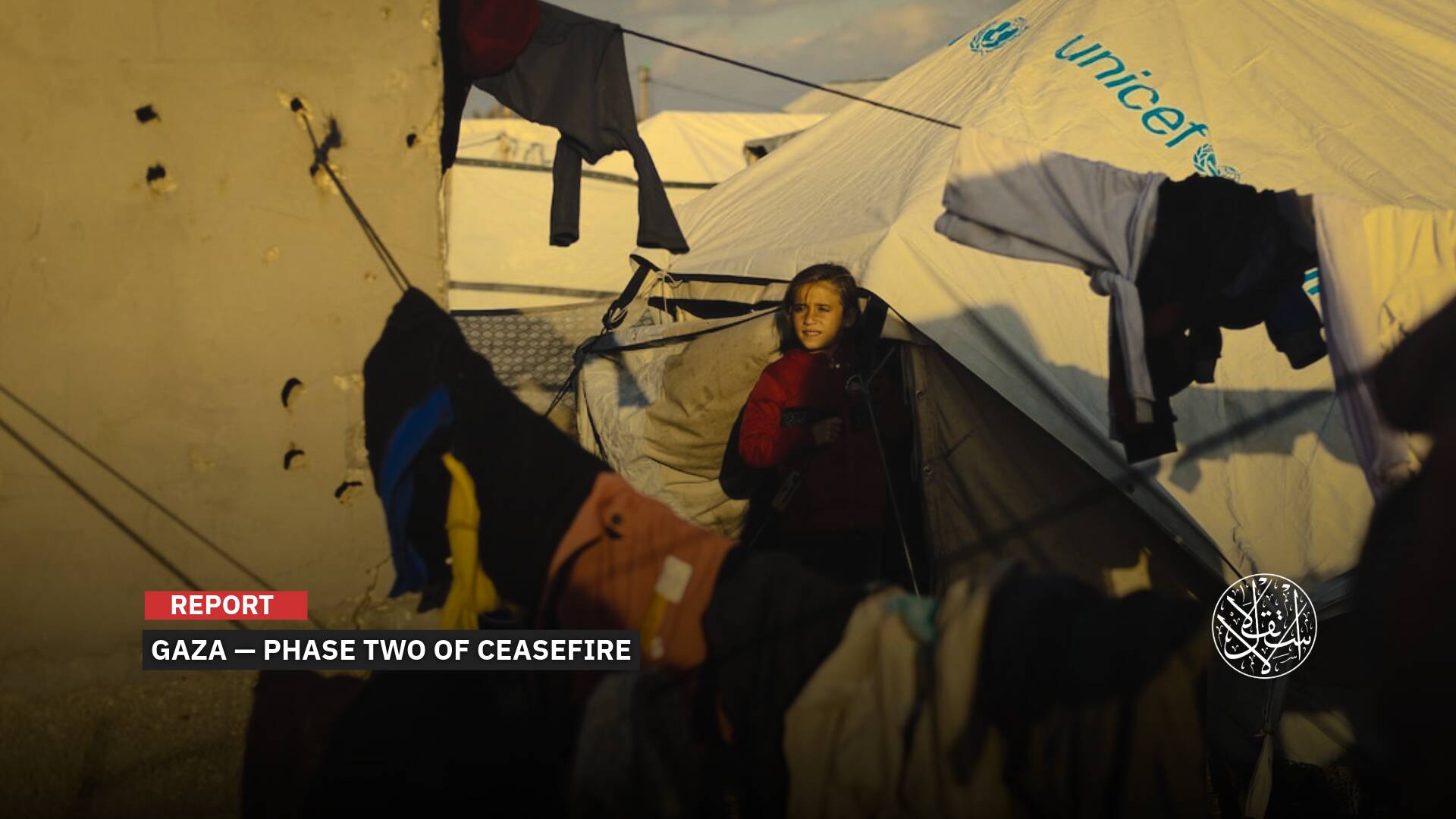

Senators Khalid Es Satte and Loubna Alawi noted that Agadir, like other cities including el-Kelaa, Taounate, Azilal, and Beni Mellal, is experiencing unprecedented protests over poor health services.

In a written question to the prime minister dated September 17, the senators warned that the situation has led to disorder and chaos within this vital public facility, increasing costs for patients and their families. They demanded disclosure of the measures the government intends to take to improve public hospital services and ensure quality across Morocco’s regions and provinces.

Political Accountability

Halima Chouika, deputy secretary-general of Morocco’s National Labor Union, said Moroccans have been “burned by Akhannouch’s poor governance like never before, in a way unseen since independence.”

Speaking to Al-Estiklal, Chouika predicted that this will have serious electoral consequences for Prime Minister Aziz Akhannouch in 2026, arguing that his mismanagement has fully exposed both his personal failures and those of his government.

“Akhannouch has no political capital or statesmanlike profile, and his tenure has been marked by self-interest rather than concern for the public good.”

“Moroccans’ lack of engagement with his recent televised address underscores his limited popularity,” Chouika added.

“That broadcast revealed that he relies on scripted answers and does not hesitate to spread misinformation; the upcoming legislative elections will serve as a key moment for citizens to judge the economic and social harm inflicted under his administration, including declining living standards.”

Chouika said that respecting the election authorities’ adherence to the law and the guidance of King Mohammed VI on proper electoral preparation would be enough to push Akhannouch out of power after a full term “of selling illusions and delivering catastrophic results for Moroccans.”

Despite Akhannouch’s government promoting a “social state” agenda, the 2025 Global Health Care Index, released in July by data site Numbeo, exposed a starkly different reality.

The semi-annual ranking placed Morocco 94th out of 99 countries, with a score of 47 for medical service quality and 80.6 for health system structure. Among African countries, Morocco ranked last, trailing South Africa (49th globally), Kenya, Tunisia, Ghana, Algeria, Nigeria, and Egypt. Notably, the index included only eight African nations, making Morocco’s position particularly concerning in the continental context.

The report recorded the lowest patient satisfaction in waiting times, at just 33.88 percent. Other metrics fared only slightly better: staff efficiency 49.4 percent, procedural speed 45.37 percent, equipment availability 50.62 percent, accuracy of medical reports 47.8 percent, quality of treatment 46.89 percent, satisfaction with cost of care 46.09 percent, and patient comfort 56.75 percent.

City-level data were equally troubling. Rabat, the political capital, ranked 303rd globally, followed by Casablanca at 310th out of 314 cities surveyed, highlighting the poor quality of services even in Morocco’s largest urban centers.

Sources

- Catastrophic Conditions at Agadir Hospital Spur Public Protests, Prompt Health Minister to Face Scrutiny [Arabic]

- Agadir Protests Over Health System Failures Turn into a Public Trial of Akhannouch as Mayor and Prime Minister [Arabic]

- Africa: Health Care Index by Country 2025 Mid-Year

- Protests Escalate Over Failing Health System, Lawmakers Call for Immediate Action [Arabic]