How Have the Consumption Habits of Europeans Changed Due to Inflation?

The Wall Street Journal reported on Monday that Europeans are confronting a new economic reality that they have not experienced for decades: their once-enviable living standards are losing their shine as they become poorer and their purchasing power dwindles.

The report painted a grim picture of how inflation has forced the French to cut back on their famous meals and red wine, reduced meat and dairy consumption to the lowest level in three decades, and threatened the organic food market that was once flourishing.

In Italy, pasta prices soared so much that the government had to intervene quickly and hold a crisis meeting in May to keep them under control after they jumped to more than double the national inflation rate.

In Finland, the government urged its citizens to use steam baths on stormy days when energy is cheaper.

The impact of the crisis reached the middle class, where citizens in Brussels, one of the richest cities in Europe, stood in queues to get groceries at half price from stores that sell food whose shelf life is about to expire.

The report indicated that the signs of the current crisis on the European continent began a long time ago with increasing aging rates that in turn negatively affected growth rates in general. Another blow came from the Covid-19 pandemic, and a third from the war in Ukraine.

The American newspaper argued that government moves had exacerbated the crisis rather than solved it, as financial aid was directed to business owners, and consumers were left without financial support in the face of rising prices.

This is a path contrary to what the United States took, which directed its support directly to citizens.

Citing the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), The Wall Street Journal explained that wage values have declined by 3% in Germany since 2019, by 3.5% in Italy and Spain, and 6% in Greece due to inflation and weak purchasing power, while real wage values in the United States rose during that period by 6%.

Record High

According to Eurostat, the EU statistics office, annual inflation across the 19 countries that use the euro hit 4.9% in November, driven mainly by soaring energy prices.

That’s the highest rate since 1997 when the European Union started collecting data in preparation for the launch of the euro two years later, and up from 4.1% in October.

The inflation rate varied across the EU member states, with Estonia, Lithuania, and Poland having the highest rates and Malta, Portugal, and Finland having the lowest rates.

Energy prices rose by 27.4% in November, while services inflation was 2.7%.

Europe is paying record prices for energy due to a combination of factors, including low gas reserves, high demand, reduced supply from Russia, and rising carbon prices.

A winter crisis looms as many households struggle to afford their heating bills.

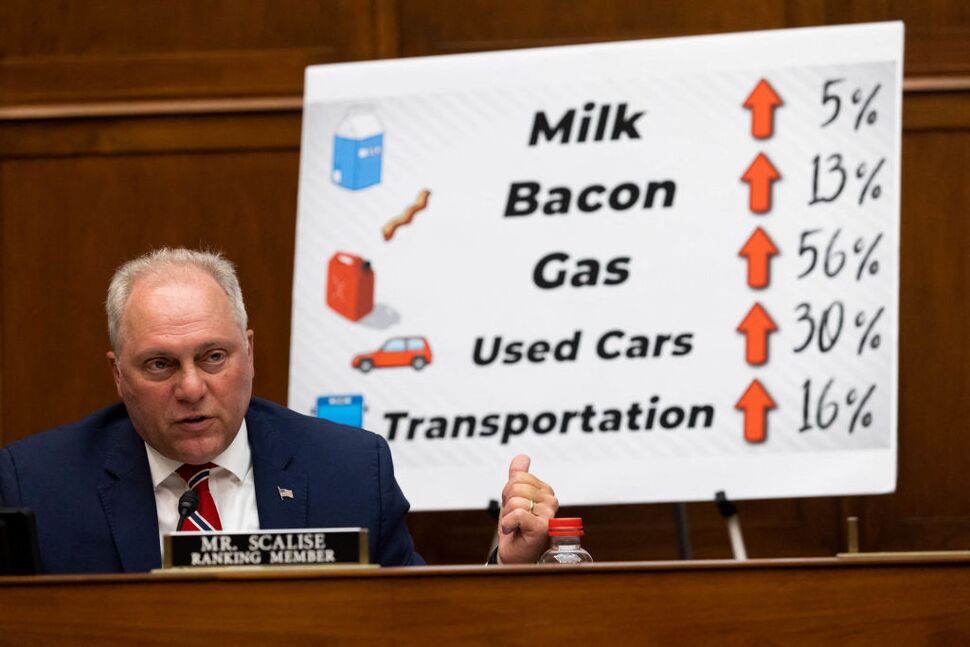

While Europe is facing a severe inflation shock, the United States is also struggling with its own economic crisis, which has caused difficulties for many Americans.

The website Axios said that life is about to become much more expensive for millions of American families, as many of the safety net programs that were allocated to combat the consequences of the pandemic will end at roughly the same time this fall, creating huge economic pressures on millions of families.

The U.S. annual inflation rate reached 6.8% in November, the highest since June 1982.

The main drivers of inflation were energy, food, shelter, transportation services, and new vehicles.

The Federal Reserve has signaled that it will accelerate its tapering of bond purchases and raise interest rates sooner than expected to combat inflation.

Challenge for Policymakers

The surge in inflation poses a challenge for policymakers on both sides of the Atlantic, as they have to balance between supporting economic recovery and maintaining price stability.

The European Central Bank (ECB) has maintained its ultra-loose monetary policy stance despite rising inflation expectations, arguing that the inflation spike is temporary and largely driven by external factors.

The ECB has also emphasized the need for more fiscal stimulus from the European governments, especially in the form of the Next Generation EU recovery fund, which aims to provide €750 billion ($850 billion) of grants and loans to boost green and digital transformation in the bloc.

However, some economists and politicians have criticized the ECB for being too complacent and risking its credibility as an inflation-fighter.

They have called for a more hawkish approach to monetary policy, including tapering its bond-buying program and preparing for interest rate hikes.

The U.S. Federal Reserve, on the other hand, has acknowledged that inflation is higher and more persistent than expected, and has revised its outlook accordingly.

The Fed has announced that it will reduce its monthly bond purchases by $30 billion starting in January instead of $15 billion as previously planned.

It also indicated that it could raise its benchmark interest rate three times next year, up from two times in its previous projection.

The Fed has faced pressure from some lawmakers and market participants to act more aggressively to curb inflation, which is eroding the living standards of many Americans, especially low-income and middle-class families.

However, the Fed has also warned that tightening monetary policy too quickly could jeopardize the economic recovery and the labor market, which is still below its pre-pandemic level.

The Fed has also urged Congress to pass President Joe Biden’s Build Back Better agenda, which includes spending on social programs, infrastructure, climate change, and health care.

The Fed argues that such investments would boost the long-term growth potential and productivity of the U.S. economy and help ease supply bottlenecks and inflationary pressures.

However, Biden’s plan faces strong opposition from Republicans and some moderate Democrats, who are concerned about its price tag and its impact on the federal deficit and debt. The plan’s fate remains uncertain as it awaits a vote in the Senate.

A New Normal?

As inflation continues to rise in Europe and the United States, many consumers and businesses are wondering whether this is a temporary phenomenon or a new normal.

Some analysts expect inflation to moderate in 2022 as supply and demand imbalances ease and base effects fade. Others warn that inflation could persist or even accelerate due to structural factors such as aging populations, rising wages, higher taxes, and climate change policies.

In any case, inflation is likely to remain a key issue for policymakers and voters in both regions in the coming months and years. How they respond to this challenge will have significant implications for their economic performance, social welfare, and political stability.

According to the latest figures from Eurostat, the European Commission’s statistics office, in 2022, there were 95.3 million people in the European Union at risk of falling below the poverty line, equivalent to 21.6% of the EU population.

This means that more than one in five Europeans were living in households with an income below 60% of the national median income, which varies widely across EU member states.

The statistics office also indicated that during last year, more than a fifth (22.4%) of EU residents living in households with children were at risk of poverty or social exclusion, compared to 20.5% of those living in households without children.

In 2021, 73.7 million people in the European Union were at risk of poverty, while 27 million suffered severe material and social deprivation, and 29.3 million lived in low-work-intensity households.

These numbers are likely to have increased in 2022 due to the impact of the energy crisis, which caused a surge in electricity and gas prices across Europe, making it harder for many households to heat their homes and meet their energy needs.

Before the crisis, nearly 7% of EU residents were unable to keep their homes warm in 2021. The situation varied across EU countries, with the largest proportion of people unable to keep their homes sufficiently warm reported in Bulgaria (24%), Lithuania (23%), Cyprus (19%), Greece (18%), and Portugal (16%).