Religion and the State in Israel: A Dialectical Relationship Since the Establishment of Zionism

Preface

The Relationship Between Zionism and Religion

Religion and the State in Israel

Religious and Ritual Commitment as a Norm of Successive Governments

Religious Parties and Their Influence on Government and Political Decision-Making

Religious and Secular Institutions, Who is Interfering in Whose Work?

Conclusion: Is Israel a Secular Country?

Preface

If the brief concept of secularism, that almost everyone agrees on, is the separation of religion from the state, then the Israeli model of secularism has a peculiarity that makes it different, and this paper tries to follow the concept of secularism in Israel and its nature, and whether there is a true separation of religion from the state in Israel or not, and the roles religion and its institutions have been playing since the emergence of Zionism and after the declaration of the state, and up to the present day.

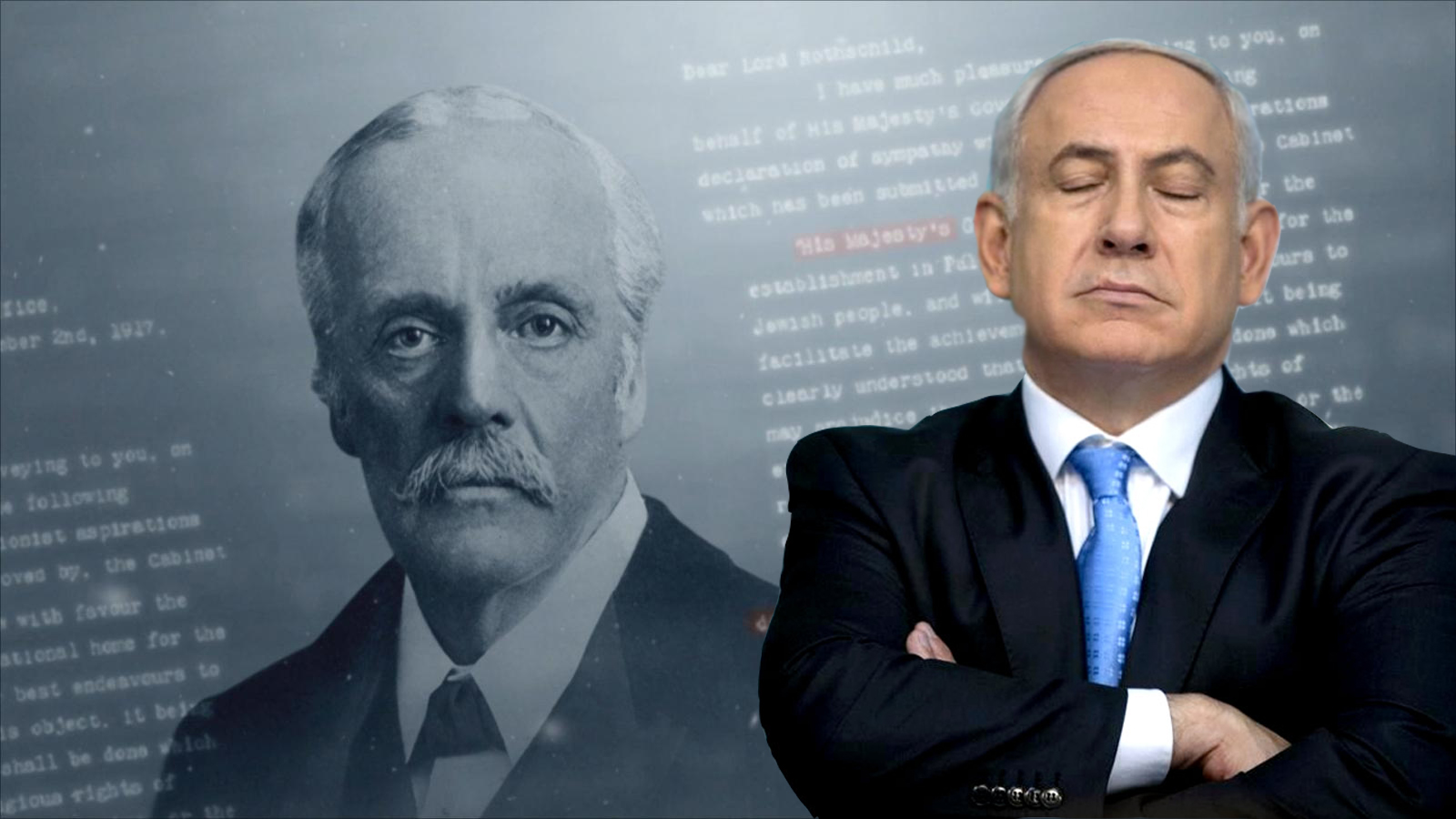

The debate in Israel about the relationship between religion and the state can be traced back to a number of Jewish philosophers, each representing a trend that was later adopted by one of the modern Zionist trends, on top of which the Jewish philosopher Moses ben Maimon, commonly known as Maimonides (1138–1204 AD).

Maimonides was concerned with understanding the Torah as the true expression of political philosophy, and that implementing the commandments of the Torah is the way to reach true happiness, and that one of the duties of the king or ruler―who is considered in the Halakhah (Jewish religious laws) to represent the idea of the state’s independence―is to take upon himself the implementation of the teachings of the Torah, or impose it when necessary.

This vision, in which Maimonides was influenced by the Muslim theologians of his time, contradicts the modern reality in Israel, since it displays a reality that is far from the ideal image depicted by the Halakhah, and the present-day state of Israel is a new reality that was not expected in the religious heritage in the era of Maimonides.

On this basis, we should not be surprised that the religious Jew will face great difficulty in accurately determining the relationship of the state and its institutions with biblical law.

Therefore, a group of ultra-Orthodox Jews (Haredi Jews) claim that the current Jewish state, with its secular character, is not legitimate according to religious teachings. This hard-line position is a continuation of an old objection by Orthodox circles to the political Zionist movement.

However, in contrast to this negative position, religious Zionism stands a positive attitude towards Zionism and the state, and considers gathering the diaspora of Jews and achieving political independence as a sign of salvation.

The question here is how to reconcile Halakhah teachings with modern reality? The problem is how to adapt the religious concept about the nature and functions of the Jewish state to the social reality in which the majority of the Jewish public does not preserve the Torah and its teachings.

There is a psychological problem for many religious people, as they adhere to the principles of modern democracy, such as majority rule and religious freedom, which are principles based on a concept about the nature of the state that differs from that concept in traditional Judaism.

In his book “Theologico-Political Treatise,” Baruch Spinoza (1632-1677) developed a critical response to the philosophical approach of Maimonides, and presented an extensive analysis of the relationship between the state and religion, and presented a different secular position based on his understanding of the foundations of Judaism.

Spinoza was linked to the intellectual history of modern Zionism, as some Zionist leaders were attracted to his thought, such as David Ben-Gurion, in their struggle with the Orthodox heritage.

There is another important issue for this strong relationship between Spinoza and Zionism, as Spinoza made a note about the re-establishment of the Jewish state in his book saying: “If the principles of their religion do not weaken their hearts, I believe without the slightest reservation, that the Jews will rebuild their kingdom at some point, and that God will choose them once again.”

Whether this phrase was meant by Spinoza in its outward sense or by a mockery—as indicated by Dr. Hassan Hanafi—the early leaders of Zionism considered it to be true prophecy, but they interpreted it within the framework of Spinoza’s philosophy through two points, the first of which is that there are principles in the traditional Jewish religion that must be overcome in order to re-establish a Jewish state, and it appears that Spinoza was referring to the negative attitude of Orthodox Judaism that believed that achieving political salvation was a heavenly matter, in which the human hands should not interfere.

On the other hand, Spinoza believes that the re-establishment of the Jewish state is an event that requires effective solidarity from the Jewish people, and this requires a fundamental change in the basic vision of the Jews that combines the legal aspect and the need for a humanitarian initiative to achieve the political goal.

The mainstream of modern political Zionism, which eventually led to the establishment of the state of Israel, was guided by the idea of a Jewish state of a secular national character, and thus effectively adopted Spinoza’s assumptions even though he was not originally interested in establishing a Jewish state, but rather mentioned this within the framework of his critical philosophy of Judaism, so that the idea of choosing a religious-origin Israel state be eliminated from the Jews thoughts.

As for the third philosopher, Moses Mendelssohn (1729 - 1786), who was not in favor of the idea of a sharp separation between civil society and the temple or between religion and the state that appeared in John Locke, it is an incorrect idea that does not serve the interest of mankind, and at the same time, he was not in favor of the subjugation of religion to the state that appeared in Spinoza.

The public interest of Mendelssohn, for which all are united, includes spiritual and worldly matters. However, there is a fundamental difference between religion and the state in the methods of imposing duties. While among the powers of the state to impose actions beneficial to the public, the religious act is not religious unless it stems from a free and willing desire. This means that he demands full religious freedom from the state, and that religious life be based on absolute religious freedom.

This position could not be accepted in Orthodox circles, but Mendelssohn’s ideas found their primary resonance in Liberal Judaism.

There is another conception developed by the Jewish philosopher Moses Hess (1812-1875), and it is closer to the model we see in Israel today in regards to religion and state.

Hess saw that the Jewish people is a nation that mixed religion, traditions, creed, morals and sovereignty, a vision that merges between political and spiritual Zionism, or between religion and state, and this vision has become one of the main characteristics of Zionism at the present time. Confirmed in the words of Shlomo Hasson: “It is as if the Jewish public has somehow returned to the philosophy of Moshe Hess.”

It seems as if Israel has moved from the model of Spinoza in its early founding, to that of Moshe Hess nowadays.

The Relationship Between Zionism and Religion

It can be said that with the end of the political existence of the Kingdom of Judah (586 BC), the true link between the Jews became the priesthood and the practice of rituals, and religious rituals became the framework that forms the Jewish identity, and it is the one that maintains solid social relations in the absence of a independent Jewish entity.

This, of course, means that the rabbis and clerics were the ones who led the Jewish minorities in most of the countries in which they lived, and they gained an advanced position among the Jews because they were responsible for understanding the religion and practicing religious rituals. This resulted in them playing great social roles, but the most important thing is that they assumed political roles as a result of the fact that they were the link between the people of their sect and the authorities of the countries in which they live.

The High Priest of the Jews in the era of the Ottoman Empire obtained the title of Chief Rabbi (Hakham Bashi), a position made by the Ottoman Empire in order to manage the affairs of the Jews within the Jewish sects scattered throughout the country. Evidence indicates that this position transcended religious matters for non-religious actions, on top of which was the political role.

Likewise, the decision to accept the Jews of France to integrate into the state during Napoleon’s rule was due to the Paris Council of Rabbis (which consisted of 112 Jewish rabbis), and this council decided that France should have a “priority of social and political loyalty,” and as a result the Jews were receiving financial support from the state paid to the rabbis, while Napoleon also made Judaism one of the official religions in France in exchange for the Jews’s first loyalty becoming to France and being absorbed into the state’s civil and military institutions.

The Chief Rabbi in Palestine during the British Mandate was playing an important political role, especially in the period from 1936 to 1945, when this position was occupied by Rabbi Isaac Halevi Herzog, and then Ben-Zion Meir Hai Uziel.

The British mandate was keen to keep this political role of the rabbinate not prominent so that the idea of a national homeland would not turn into a political entity so that this would not lead to Arab opposition, and therefore they focused on the religious role of the rabbis.

That is, the British wanted to show the Jewish presence in Palestine as the presence of a Jewish community, because showing the political role of the rabbinate would have emphasized that the Jews in Palestine were no longer just a religious sect, and that they were seeking to establish a state with the help of the British.

Based on this political role, it goes without saying that the clergy have a great role in supporting Zionism and spreading its ideas, and there are more than countless cases in this context, for example that reviving the concept of what is known as the Promised Land belongs to the Jewish Rabbi Isaac ben Solomon Luria, known as Ha-ari, who lived in Palestine during the sixteenth century.

Rabbi Ha-ari belongs to a mystical school, and he is the owner of a revolutionary school of thought that revolted against the traditions of the past, and to which the introduction of Palestine into the circle of social and religious awareness of the Jews of the East is credited.

The rabbis of the Jews in the Islamic world sought to link the members of their sect with the thought of Rabbi Ha-ari. An example of this is Rabbi Sadqa Hussein, who assumed the leadership of the Jewish community in Iraq in 1740 and led a tangible renaissance movement to spread the thought of Ha-ari, who paid great care to the “promised land.”

Likewise, Rabbi Judah Alkalai (1798-1878) linked the messianic hopes (salvation) with national projects, and he had many activities in Europe and influenced the thought of Baruch Mitrani (1847-1919) who was calling for the revival of Hebrew and was one of the most prominent advocates of settlement in Palestine, and he established settlement bodies in Palestine to which he immigrated and where he died.

The rabbis of the East played a major role in the endorsement of Zionism among the members of the Jewish sects in the East, including what the Jewish community in Egypt did, when it conducted a massive reception for the 38th Brigade, which was established by the British in 1917 during World War I, after the continuous pursuit of Ze'ev (Vladimir) Jabotinsky, a religious zionist leader, with the aim that this brigade would defend Palestine if the war extended to it, and this brigade was sent to Egypt to complete its training.

This ceremony took place in the name of the Chief Rabbi of the Jewish community in Egypt, and when this brigade arrived in Cairo, an official ceremony was held for it in the main Jewish temple in Cairo.

For the factor of religion to be the most important factor in the spread of Zionism and its obtaining the support of the majority of Jews in Egypt for Zionism, does not mean that the matter is different in other countries, as religion and its men were the first factor in the spread of Zionism everywhere.

Rabbi Joseph Marco Baruch (1872 - 1899), who was born in Constantinople and educated in France, was one of the great advocates of Zionism. He visited Egypt and called for Jewish nationalism and the occupation of Palestine. He was the the founders of the first Zionist association in Egypt called the “Bar Kokhba Society.”

Also, many rabbis in Thessaloniki supported Zionism, headed by the Chief Rabbi there, Joseph Naour and Rabbi Yaakov Meir.

The spread of Zionism among Georgian Jews—according to the opinion of the Jewish historian Nathan Eliashvili—goes back to Rabbi David Baazov (1883-1947), who was very enthusiastic about Zionism, and to whom he is credited with awakening the nationalist sentiment among Georgian Jews.

Of course, some Zionist rabbis refused for ideological reasons. At the beginning of the emergence of political Zionism (end of the nineteenth century), some rabbis and religious institutions viewed it as involving sin, as they found in it an unwanted challenge to their leadership and authority.

This trend eased with the passage of time among Jewish Orthodoxy, and only a few of the Jewish clerics who belonged to the Neturei Karta group remained attached to it. On the contrary, a branch of those who supported Zionism made a religious branch “Mizrachi” (religious Zionism), as they said that it does not contradict religion and Zionism.

It is claimed that Zionism can achieve the expected salvation, and it is not necessary for the Savior to be a single person, and these did not consider the Zionists to be the hand of God that carries out the promise to Israel, but rather called for engaging in Zionism.While the third party rejected Zionism ideologically, but it accepted its political and military achievements, and those were who founded the “Agudat Yisrael” (Union of Israel).

There are rabbis who saw Zionism as a step in the way of fulfilling the divine promise, as “Mercaz HaRav Yeshiva” (which is like a Zionist Talmudic Rabbinic academey founded in 1923, by Abraham Isaac Kook, the first chief rabbi of Israel, and it owns the largest political theology in our contemporary time covering the subject of the State of Israel and the Jewish world more broadly) believes that secular Zionism, which was founded by Theodor Herzl in 1896, is only a first step to fulfilling the promise of Israel.

In order to achieve the decisive stage for the establishment of Israel, a harmony must be found between the sacred and the secular, between the spiritual and the political reality, and this harmony will take into account the distinction of the Jewish people and their land, and Israel will be able to achieve this goal through the influence of religious Zionism and Mercaz HaRav Yeshiva.

On the other hand, however, the rabbis’ opposition to Zionism was often a matter of calculated deceit—especially in Islamic countries—because support for Zionism would have provoked the ruling authorities in Islamic countries, which was evident in the position of Rabbi Chaim Nahum, the chief rabbi of Constantinople, who opposed Zionism for fear of provoking the anger of the Ottoman authorities, who were taking a hostile stance against Zionism.

Therefore, the rabbis’ attitudes towards Zionism changed when conditions became favorable, as happened with the Chief Rabbi of the Jews of Turkey, who turned his hostility to Zionism in support of it, and even called for a Zionist conference for the Jews of Turkey in 1919, and so did Rabbi Aharon Sasson in Baghdad, and Shafiq Ades in Basra.

It may also be true in the case of some rabbis, who have a conservative religious orientation, to say that the change of their positions on Zionism from opposition to positive interaction with its basic ideas was such as not swimming against the current, as their rejectionist positions could not distract the attention of the young Jews from the Zionist movement.

This indicates that the conflict between Zionism and the conservative religious circles was usually resolved in favor of Zionism, but in return, the rabbis of non-traditional Jews were contributing to the support of Zionism and the usurpation of Palestine.

It may be more appropriate to say that despite the diversity and contradictions between the various Zionist currents (political Zionism and religious Zionism), there was broad agreement between them about the goals, and there is also a great willingness among them to cooperate in order to achieve those goals, and the researchers determine that the religious element has existed permanently since the beginning of Zionism.

The role of religion in spreading the Zionist movement is too great to be denied. Indeed, secular Zionism has never diverged from religion, and as Orly Noy says, when Zionism tries to expand its scope of work to include all Jews in the world, this in itself is more of a religious act than a national one, and even when secular Zionism employs religion and makes Judaism a guardian of nationalism, it has thus integrated religious motives into Zionism.

Although secular Zionism, according to analysts, was what always ran the wheel in Israel, yet it did not want to separate from the religious wings, rather it was not even able to do so.

Religion and the State in Israel

The secular Zionism’s choice of Palestine specifically as a homeland for the Jews on the basis of the biblical idea of the Promised Land was a religious choice, just as building a national home on the basis of the Jewish religion, and enacting a right of return based on a religious basis to allow every Jew or judiazied by rabbis in the world to return to a the Promised Land, and employing religious passion to push Jews to emigrate to Palestine is also a religious act. In addition, the renewed call for the Judaism of the state is a racist religious call.

In this context, one of the Israeli writers wonders: “If the secularists freed themselves from religion and belief and imposed the sovereignty of the individual and their responsibility for their fate as a substitute for religion, then what was the transcendent force that pushed the creation of a national group in Palestine specifically and not in Uganda or elsewhere? All this indicates that the religious factor was, is and will remain the most important factor in the emergence and existence of this entity.”

This in turn means that despite the voices that criticize the rabbis sometimes or often, and despite the restlessness of a sector of the Zionists about the interference of parties and religious institutions in the conduct of state affairs, the advantages that religious people get, the state’s respect for biblical legislation, the increase in the influence of religious parties and forces, and the controversy surrounding the obedience of soldiers, whether do the military orders or the orders of the Torah, all have matters that indicate the strength of the relationship between religion and the state in Israel.

Shlomo Hasson depicts the relationship between religion and the state in Israel as a relationship of complementarity (or reconciliation), and this is apparent in the national, political, social and cultural sphere.

In the national sphere: this complementarity appears since the Zionist movement decided to return to the national past and the basic symbols of the Jewish people, this step was accompanied by tension and then integration between the historical home and the Holy Land that was granted within a religious promise, and between Hebrew as a modern language, Hebrew as a sacred language, and between the Tanakh (the most common name for the Hebrew Bible in the scientific community) that is, the Holy Book of the Jews (with its festivals and rituals) as a source of national culture, and the Tanakh with its religious dimension.

Zionism not only maintained its relationship with religion on the issue of returning to the Promised Land, but also in its adherence to the method of joining the Jewish people, after the establishment of the state, joining the Jewish people was linked to the process of Judaization, which is a religious act, and the debate revolved around the type of rabbis allowed to Judaize, and not about the principle of Judaization as a religious principle in itself. If every Jew is entitled to obtain citizenship in Israel, then the path to obtaining it must first pass through the process of religious conversion.

In the political sphere, the relationship of complementarity between religion and the state is evidenced by the majority avoiding using its authority to settle controversial issues, and there are arrangements that are always made to agree with the religious minority by respecting their demands in basic issues such as the Shabbat, marriage, and the approval of the provisions of the Halakhah in matters of state and education.

Since the establishment of the regime in Israel, the tendency of its democracy has been to create pragmatic agreements between religion and the state, or between parties, on the basis of observing Jewish values and common interests.

In the social sphere, the relationship of complementarity appears in the commitment of the majority of secular Jews in Israel to religious symbols and rituals. Most of the Israeli public, including the secular public, of course, is keen to integrate religious rituals into its lifestyle, such as circumcision, puberty rituals, marriage according to religious provisions, and other religious matters.

According to a social survey conducted by the Central Bureau of Statistics in 2009 targeting secularists in Israel, it showed that 82 percent always participate in Easter rituals, that 67 percent light Hanukkah candles, 29 percent are always keen to light Shabbat candles, and 26 percent always fast on Yom Kippur, and that 22 percent hold on to legal food on Easter.

The relations of complementarity at the social level are also reflected in the increasing integration of the ultra-Orthodox into political regimes, volunteerism, employment, and even in the army, and in the central role played by national-religious Judaism in shaping the state’s image in service in the army and in shaping the civilian agenda.

The relations of complementarity or reconciliation between the secular and the religious, do not prevent the existence of a state of tension between the two currents. An Israeli opinion poll conducted in 2012 revealed that the tension between secular and religious people is the second strongest tension in Israel, as 59.7 percent of the respondents chose the tension between secularists and religious people as the strongest tension, compared to 70.6 percent who chose the tension between Jews and Arabs in Israel.

Religious and Ritual Commitment as a Norm of Successive Governments

The commitment of Israeli heads of government to the Jewish religious rituals from the first government until the present day was one of the basic features that characterized the Zionist entity.

Since the first government of David Ben-Gurion, governments have been keen on this openly, regardless of whether they are left or right-wing.

None of the governments would ever have held an anti-religious position at all, and this is due to several reasons, one of which is the necessity to respect religion very much in a country that was originally established on a religious basis. In addition, the secular parties’ compulsion to enter into coalitions to form successive governments imposed on them to show this commitment and exaggerate it, and make concessions to maintain the continuation of the ruling coalitions.

In this regard, there are two stark examples related to the position of religious Jews from Menachem Begin and Yitzhak Rabin, while the position was positive regarding the first when many members of the Gush Emunim (a national religious group that arose after the 1973 Arab–Israeli War to encourage settlement) commented, after the victory of Menachem Begin in the 1977 elections which the Likud won 43 seats, by saying: “The era of Christ has come,” after Begin answered a question of whether he would annex the West Bank of the Jordan River, saying: “We cannot talk about annexing land that is an integral part of Israel.”

On the other hand, the entry of the latter, Yitzhak Rabin, in the Oslo Agreement was the main reason for the anger of the religious masses, accusing him of treason and selling the land, and considering him an enemy of the Israeli people. Indeed, some clerics declared that they would not be sorry if Rabin was killed, and this ultimately led to his assassination by the hands of Yigal Amir, who was educated in religious schools and joined Bar Ilan University, which was founded by the national religious movement.

Religious parties were able to obtain state approval to support religious schools, thus increasing their number. They were also able to obtain optional exemption from military service for students of Talmudic schools, despite the compulsory military service in Israel, in addition to the control of religious institutions over everything related to personal status laws.

Even with regard to the issue of burying the dead, the manner in which it takes place, the extent to which the provisions of Halakhah are observed or not, and the religious establishment’s control of all cemeteries and religious services in relation, while secular Jews do not have a choice in this regard.

There is a story circulating that confirms the extent of the exaggeration of the clergy in showing this when one of the Jewish immigrants of Russian origin died in a car accident, and during the burial procedures it was found that he was not circumcised, so the rabbis issued a legal opinion that he must be circumcised before burial in order to become a member of the the Israelites.

Religious forces have also succeeded in preventing “El Al” airports’ airplanes from flying on Saturdays (Shabbat). In this, Shulamit Aloni says: “Religion will enter your kitchens, and the religious will soon spread in your streets, on the shores of your beaches, in your schools, and on your sleeping beds.”

Since the establishment of Israel, what is known as the Military Rabbinate has been established within the army, whose role has grown with the passage of time, and has become carrying out everything related to religious rituals in the army, and the leaders of this rabbinate are distributed to be part of the leadership of each battalion of the Israeli army.

Its work deals with every small and big thing that may be related to matters Halakhah, starting with observing the rites of the Shabbat, the military conditions in which these rituals can be bypassed, places of worship within the military units, how to purify them, lighting candles on holidays, prayers and supplications and their various timings, religious dress, follow up on the approval of food supplies in accordance with the religious teachings, marriage and divorce ceremonies for soldiers, burial ceremonies for the dead soldiers, follow-up of their treatment, and ensuring that military units allow soldiers to perform their prayers.

It is also important to mention here that the Military Rabbinate is more inclined to follow the opinions of its religious leaders than its military leadership.

There are many examples and models all confirming that the issue of respecting religious rituals was and still is of great importance to successive governments to this day, and whether that was from the conviction of the secular parties leading the governments, whether right-wing or left-wing, or as a matter of pragmatic behavior, that means that they have realized the importance of this for the majority of the Jews, especially the religious ones, who in turn realized that religion is the master of power.

Religious Parties and Their Influence on Governments and Political Decision-Making

The nature of the political situation in Israel and the constant need to form coalition governments gave great importance, that does not commensurate with their real size, to small parties, these parties impose their words on the big parties winning the elections, which in turn often bowed to their will.

Ben-Gurion formed his first and second coalition government, which included 3 ministers from the list of religious parties that won 16 seats in the first Knesset elections, and Ben-Gurion, leader of the left-wing Mapai Party, pledged that he would not harm the Jewish religious traditions to please these parties.

In light of this situation, the religious parties obtained from an early age complete freedom to operate according to their will, and these religious parties have used their full energy in running their own religious educational system.

Since the first day in announcing the establishment of the Zionist entity, Saturday has been set as an official holiday in which all public state institutions, private institutions and shops will be suspended with limited exceptions in respect of Jewish law, and the religious parties and students of religious education were granted special privileges that came later—as mentioned earlier—to the point of exempting students of religious schools (Yeshiva) from military service.

With the emergence of the extremist religious Shas Party (1984), religious people entered the field of using the media, and the party’s rabbis criticized what they called “the emptiness and rottenness of the non-religious Israeli life,” and they were achieving great successes in this regard.

This of course led to an increase in the gains of the religious parties that often participated in the Israeli governments, whether led by the left or the right, and more often than not, they were pressing for more gains.

The leaders of the ultra-Orthodox Shas Party, which was participating in the 1992 government led by the Labor Party headed by Yitzhak Rabin, and the Meretz Party, both left-wingers, threatened to abandon the government because of their objection to the then Minister of Education, Shulamit Aloni, eating her lunch in a restaurant that does not take into account religious dietary laws (Kashrut), as well as their objection to some of her religious statements until Rabin himself forced her to apologize to overcome this matter.

That prompted the Israeli journalist, Yoel Marcus, to say: “Every concession on these matters only leads to encouragement to ask for more,” and he says elsewhere sarcastically: “ We can also expect that every minister and every member of the Knesset will be asked to accompany a Kashrut food inspector.”

It is worth noting here that Shas Party won only six seats, compared to 44 for the Labor Party, and 12 for Meretz.

Mercaz Harav Yeshiva in Jerusalem had a prominent role in influencing many of the religious and political figures who had a role in establishing Gush Emunim, as well as its role in establishing many settlements in the West Bank.

Many followers of religious Zionism who merged in the Mercaz Harav Yeshiva had a pioneering role in leading the opposition against Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin regarding the Oslo Accords with the Palestine Liberation Organization in 1993, and against Prime Minister Ariel Sharon upon the unilateral withdrawal from the Gaza Strip and the evacuation of some settlements in the West Bank in 2005.

The funerals of clerics were an important opportunity to bring secular party leaderships closer to religious parties and their supporters. At the funeral of Mordechai Eliyahu in 2010 (who is the former Chief Rabbi of Israel, who won his position on a nomination by the National Religious Party), the Speaker of the Knesset, Reuven Rivlin (Likud), said: “Rabbi Eliyahu was of those great people whose commandments will remain as a pillar of fire for all the clergy,”—note that the word pillar of fire is a biblical word that came in the context of the Lord’s appearance to Moses, and it indicates the extent to which the religious sense penetrated the leaderships of the Israelites.

In the same context, Netanyahu (the prime minister at the time) lamented Rabbi Eliyahu, saying: “He was at the forefront of the leaders of religious Zionism, was loyal to our people, and always loved the sayings of the Torah.” It is reported that Menachem Begin visited this rabbi on the eve of the bombing of the Iraqi nuclear reactor to obtain his approval.

Eliyahu held the position of Chief Rabbi for 10 years, during which he issued a legal opinion prohibiting the ceding of any part of the land to the Palestinians, saw that the lands of southern Lebanon and parts of Syria are part of the land of the Jews, and supported the First Lebanon War, perceiving it as a war based on religious commandments.

At his funeral, the Mayor of Jerusalem, Nir Barkat, said: “I had a great opportunity to meet the Rabbi Eliyahu and told him that all the people of Israel love him, religious and non-religious, eastern and western, and he also commanded me to preserve Jerusalem, and for me, this is something that must be implemented.”

Religious and Secular Institutions, Who is Interfering in Whose Work?

If we turn to the current situation in the relationship between religion and the state in Israel, then the first thing we notice is that the parties to the conflict (secular and religious) do not preserve the purity of their original ideas for various reasons, one of which is of course the pragmatic approach that dominates the political arena, but the conflict still exists between the two sides.

It suffices to clarify it that we refer to the issue of integrating the religious rabbinic into the framework of the state, as the trend was to integrate the Orthodox (Zionist) Rabbinate into the state system, on the basis that the state law regulates the election or appointment of central and local rabbinical authorities as well as judicial institutions and administrative bodies, and all these institutions are funded by the state and supervised by the Supreme Court of Israel.

The incorporation of the rabbinate into the state framework did not lead to much opposition, but the initial acceptance of the idea of integration was based on two opposing ideologies.

The process of incorporating the rabbinical institutions into the state framework—in the eyes of the Zionist religious circles—was positive evidence of the state’s association with Judaism.

These circles denied, in principle, the secularism of the State of Israel, and therefore considered the official recognition of the rabbinate as an important measure to deepen the Jewish character of the state.

As for the political teachings of Maimonides, it can be said that the realization of religion through the official rabbinical institutions is the realization of the natural fate of the Jewish state according to the view of these circles.

On the other hand, the secular political establishment had a completely different view, as David Ben-Gurion, who is considered the founder of the existing arrangement between religion and the state in Israel, is quoted in his response to a question about the relationship of religion with the state, saying: “You are demanding the separation of religion from the state so that religion becomes an independent element that the political government should handle?! I reject this separation, I want the state to hold religion in its hand.”

Ben-Gurion was a fan of Spinoza, aware of the implications of Spinoza’s theory, and was keen that religion shall be subordinate to the state in order to stabilize political power.

It was natural that this ideological conflict in integrating the rabbinate into the state would lead to conflicts, especially with regard to setting the limits of the rabbinate’s work and its freedom.

The secular approach tended to see the rabbinate as an ordinary administrative body, tasked with performing specific functions determined by the state, and thus under the supervision of the Supreme Court of Israel, and that any activity not mentioned in the law be a prohibited deviation.

For its part, the rabbinate saw itself as an independent body, free to perform all the tasks and functions entrusted to it within the framework of the religious legal system (Halakhah).

Given these differences in approach, it was not surprising that intense conflicts arose between the rabbinate and the state, although most of them ended in some kind of compromise.

The National Religious Party has been a partner in the Zionist project from the start, but despite this it played a marginal role in the political system for a long time.

Beginning in the seventies, this movement played a pioneering role in the settlement process, and later on it became an influential player in the Zionist army, and statistics reveal that this party has become a powerful and influential movement in the Israeli institutions.

This party constitutes a percentage not exceeding one-tenth of the total population in Israel, but its percentage among the officers in the Zionist army—despite that—exceeds 40 percent of the total army officers.

Moreover, members of this religious party are at the forefront of research institutes of a national character, which are strongly involved in developing educational curricula and legislation, and in defining policies.

Among the most prominent of these institutes are the Shalem Center, the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs, and the Institute for Zionist Strategies. In addition, the National Religious Party was the one that established Bar-Ilan University in 1950, which is the second largest university in Israel, and it still controls it. The university was named after Rabbi Meir Bar-Ilan, one of the leaders of religious Zionism and the head of the Mizrachi movement, which belongs to religious Zionism.

Conclusion: Is Israel a Secular State?

What determines the identity of the state, whether it is secular or religious, is the existence of a constitution that can resolve this issue, and with regard to Israel, it is known that the early leaders avoided drafting a constitution for the state in order not to lead to a disagreement between the Israeli religious and secular forces that may affect even those points agreed upon by everyone, what may destroy the establishment of the Zionist project.

The Israeli Knesset website notes that one of the reasons for not establishing a constitution for Israel is to avoid a cultural war between religious and secular people over the identity of the state.

This means that the talk of Israeli leaders and thinkers—secular or religious—that the identity of the state is secular or religious is related to the purpose pursued by each of the two parties, and here comes the role of the historical circumstance, and the political and social reality to resolve this issue.

This paper has detailed how the birth of Israel was a religious upbringing with the “Return to Zion” (to the Promised Land), and how the political and social reality witnessed an increasing rise in the influence of religious forces and parties in Israeli politics.

It also listed the major gains achieved by Israel, which increased even more after its victory in the Six-Day War (1967), so much so that all the religious public and broad sectors of the secular considered this victory a divine miracle that was accomplished with heavenly help for the Jews, and the secular leaders themselves were using religious symbols and occult religious ideas, and the strength of the orientation towards religious salvation increased. In both Judaism and Zionism, victory was considered a sign of Salvation that was approaching, and the relationship between religion and politics became more brilliant: religion serves national policy, and national policy is to implement religious commandments.

The Zionist writer Yair Auron commented on the shift towards religion that took place after the victory of Israel in the Six-Day War, saying: “The trend became Jewish first, and then Israeli.”

Students often mistake Israeli secularism and imagine that it must be identical with the Western model, and they forget that the gap is wide between the Israeli case and the case in the Western model.

This is evident from the position of Israeli Professor Shaul Rosenfeld in his speech to those calling for the separation of religion from the state in Israel, and how they ignore the Israeli peculiarity while trying to imitate the Western secular models, that in the most extreme, do not separate religion and the state altogether, and they also ignore the fact that the Jewish presence in Israel was based upon a historical past, the core of which is purely religious, just as the Jewish religion is the one that shaped across generations the cultural, social, linguistic and spiritual reality of society, even for those who do not believe in the Jewish religion.

Ben-Gurion—the visionary for the relationship between religion and the state—wanted there to be no separation between religion and the state, and he also wanted the state to be in control of religion and hold on to it. From what we have presented in this paper, it seems that success was achieved in the first, but little did it happen in the second.