How the Far-Right’s Popularity Reached Its Highest Levels in Germany

Prominent figures in Germany’s political mainstream are raising the alarm after a new poll showed support for the country’s leading far-right party at a record high.

The left in Germany suffers from major problems, as the traffic light coalition (Ampelkoalition) in Berlin—composed of the Social Democratic Party (SDP), the Free Democratic Party (FDP), and the Greens—led by Olaf Scholz, is becoming increasingly unpopular among Germans due to the mounting economic crisis.

After being defeated by the center-right Christian Democrats Union (CDU) in regional opinion polls, the traffic light coalition failed to stem the rise of the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD), which gained 18% in recent polls.

After focusing on the issues of refugees and Islam, the German far-right is waging a new battle against the government’s climate policy, allowing it to increase its popular score to its highest levels in the post-World War II period.

How can the progress of the far-right be explained, even though the party suffers from struggles for influence among its leaders, is subject to close monitoring by the intelligence services, and does not present striking counter-proposals?

Populist Rhetoric

Two opinion polls, the results of which were published at the end of last week, showed a significant lead for the AfD to constitute a major competitor to the SDP, led by Olaf Scholz, who is now in a difficult position.

The first poll for the ARD network gives the AfD 18% of the vote, while this percentage reaches 19% in the second opinion poll, the results of which are reported by the Bild newspaper in its issue of June 4, 2023, speaking of a shocking poll.

The AfD has never recorded this percentage, and it reflects the doubling of its popularity after it achieved a result that barely exceeded 10% in the 2021 elections.

A recent poll predicted that the far-right party would come second in the next general election, ahead of the ruling SDP.

As for the Greens, members of the ruling coalition, they recorded a significant decline to 13% or 14%.

On the other hand, the conservatives of the CDU and the SDP, who moved to the opposition after the exit of former Chancellor Angela Merkel from political action, topped the list, as they collected 27% or 28% of the vote intentions, but they do not record more progress.

The AfD benefits first from the decline in the popularity of the ruling coalition, with support for its performance declining to 20% of the Germans, under the weight of inflation, deflation, and fears resulting from the Russian war on Ukraine, according to what the ARD Network investigation showed.

Although the Conservatives are leading the polls, they are finding it difficult to embody an alternative.

Norbert Roettgen, a senior lawmaker for the main opposition Christian Democrats, described the poll as a disaster and an alarm signal for all parties in the center.

Roettgen, whose party came in at 29% in the same survey, said his own center-right party should ask itself why it hasn’t profited as much from voters’ disillusionment with the current government, which replaced a coalition led by Angela Merkel.

Another Christian Democrat, Serap Guler, said AfD’s growing support should alarm all democratic parties.

Sawsan Chebli, a member of the Social Democrats, tweeted after the polls were published: “The AfD is at 18%. People, wake the hell up!”

Extreme Obsessions

Even if two-thirds of voters still put immigration at the forefront of their concerns, the far-right party appears to be benefiting from its growing opposition to climate-friendly measures.

“We don’t want a policy that protects the climate, because the climate has always changed over time,” said Beatrix von Storch, the deputy leader of the AfD.

The AfD took advantage of its rise to the Greens’ project to ban heating by fossil energies from next year, a proposition that is opposed even within the ruling coalition by the liberals.

Chancellor Scholz, a year and a half after coming to power, still finds it difficult to control his partners, with the Bild newspaper even writing: “The coalition house is on fire.”

The far-right AfD’s co-leader, Tino Chrupalla, is now focusing his criticism on the Greens, stressing that it is the only party that categorically refuses to form a coalition with it.

In a statement to Funke Mediengruppe newspapers, he said: “Citizens can see where the policy of the Greens is leading—to economic war, inflation, and the decline of the industrial sector.”

The AfD made Vice-Chancellor and Minister of the Environment, Economy and Climate Robert Habeck a scapegoat for all the problems the country faces.

The minister from the Greens, who is considered a possible candidate for the chancellorship in 2025, is the subject of criticism from the Bild newspaper, the most circulated in Germany, and among the CDU, which accuses him of seeking to impose restrictions on the use of cars and individual heating.

Habeck also embodies, in the opinion of Mario Voigt, head of the CDU in Thuringia, a hegemonic state controlled by energy intelligence, in a reminiscence of the former secret police in East Germany (Stasi).

The minister stands behind the main confusion in recent days, as he expressed his dissatisfaction with the performance of the ruling coalition after he was fed up with the criticism leveled at him for giving priority to renewable energies.

Habeck criticized his liberal allies for blocking his plan, which was leaked to the press, to ban the installation of new oil or gas heating systems next year.

In turn, Christian Lindner, leader of Germany’s pro-business FDP, said that this ban would have catastrophic economic and social consequences.

The SDP also criticized the ban, with MP Dirk Wiese expressing concern for all those who cannot afford to spend 20 to 30 thousand euros on a new heating system.

In this context, political scientist Ursula Munch told AFP that the AfD focused on the issue of climate protection measures and managed to mobilize and create an atmosphere rejecting this policy.

Munch relied on a study prepared by researchers from the University of Dresden in 2022, which shows a correlation between projects to establish wind turbine farms and voting for the AfD, especially in former East Germany.

The far-right party also addressed the issue of the upcoming closure of coal-fired power plants in 2030, as it called on its deputies to abandon the project.

Only 18% of far-right voters consider global warming to be human-induced, compared to 73% of The Greens supporters, according to the Dresden researchers’ study.

In turn, political expert Hayo Funk summed up the situation to AFP, saying: “The far-right party succeeds in taking advantage of the ruling coalition’s shortcomings in the field of communication and concerns related to the cost of heating.”

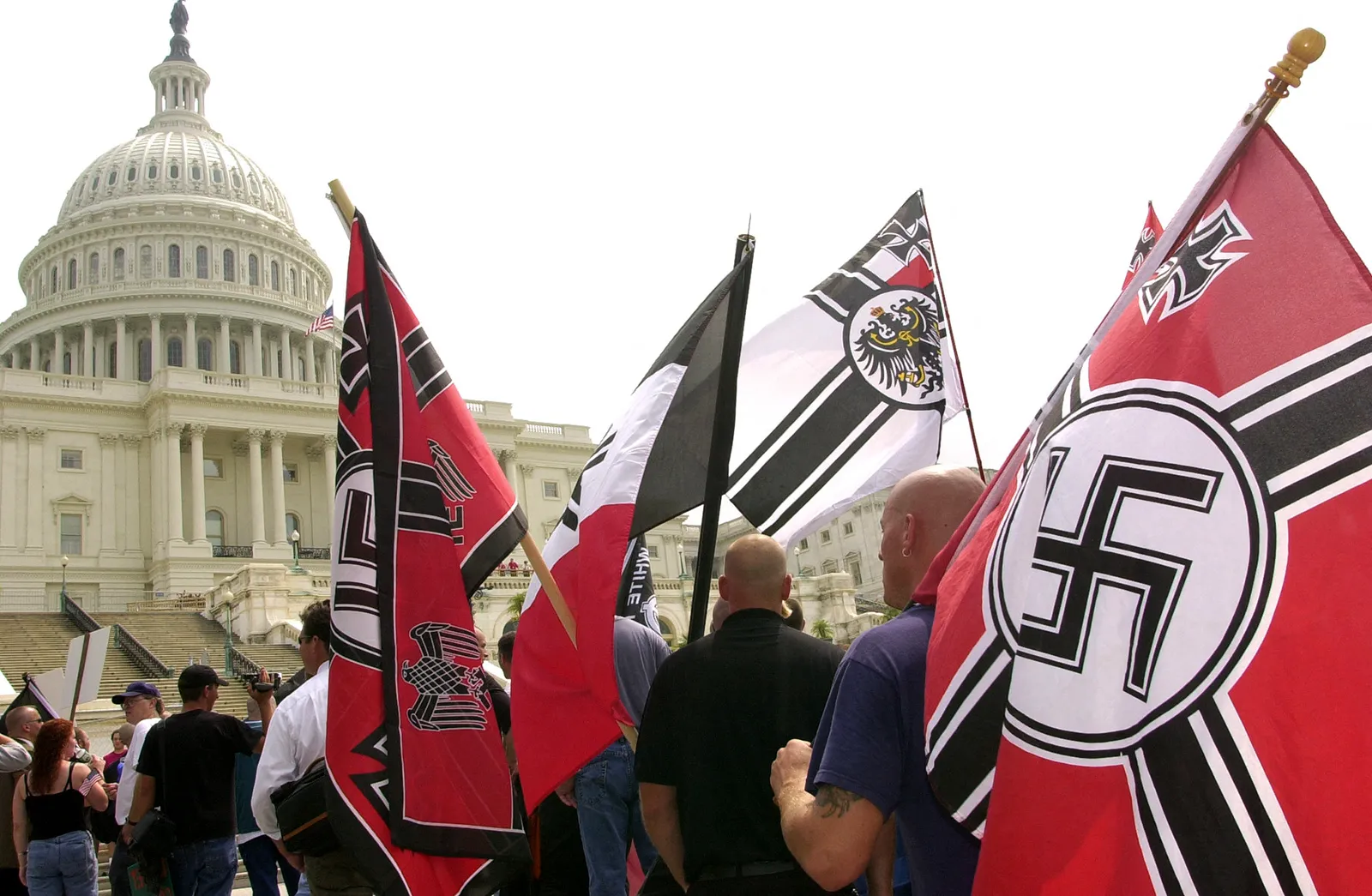

The Rise of the Far Right

Founded in 2013 as a party of professors disgruntled by the euro crisis, the AfD was reborn after the Syrian refugee crisis two years later as a right-wing populist force spreading anti-immigrant and anti-Muslim rhetoric.

In 2017, it surged into Germany’s parliament at a general election, coming in third, with the highest vote share (12.6%) for any far-right party since the Second World War.

Although mainstream parties refuse to cooperate with the AfD, its successes at the regional level have forced its rivals to form unwieldy coalitions to keep the far right out of power in state parliaments.

The party had a run of electoral setbacks in 2020 and 2021, with its lockdown-skeptic stance failing to resonate widely even as coronavirus-related protests helped to stimulate far-right conspiracy theorists.

The protests are blamed for fuelling the rise of the Reichsbuerger (Citizens of the Reich) movement, which rejects the legitimacy of the post-war German state and was linked to the alleged armed plots.

One of the suspected plotters arrested in December was a former AfD member of parliament, Birgit Malsack-Winkelmann, whose alleged involvement concerns security in parliament.

“The truth is that the AfD has long been the parliamentary arm of anti-democratic movements,” tweeted Katja Mast of the center-left SPD after the arrest of the plotters on December 7.

A member of parliament from 2017 to 2021, Malsack-Winkelmann had privileged access to the complex of parliamentary buildings in Berlin and highly sensitive knowledge of security arrangements there.

Following her arrest, Malsack-Winkelmann’s name was quickly removed from the AfD’s website.

“Operation Shadows,” one of the largest police operations in the history of the Federal Republic of Germany, did not elicit much of a reaction from AfD co-leaders Alice Weidel and Tino Chrupalla.

The Reichsbuerger movement is said to include some 23,000 people in Germany, about 10% of which the authorities described as orientated toward violence.

The recent developments serve as a reminder of an incident in 2020 when aggressive demonstrators against COVID-19 restrictions managed to penetrate the Bundestag with visitors’ passes obtained through AfD lawmakers.

Last January, a former far-right AfD lawmaker was charged in court after allegedly calling for the overthrow of the German state when he was part of the storming of the steps of the Reichstag in 2020.

Meanwhile, calls for increased monitoring of the AfD by the BfV are growing.

Bavaria’s State Premier Markus Söder of the center-right Christian Social Union (CSU) described the AfD as closely interwoven with the Reichsburger scene.

“It is increasingly developing into a rallying point for precisely such right-wing extremist forces as well, it downright attracts them,” he said.

SPD co-leader Lars Klingbeil agreed: “The entire AfD belongs on the watch list of the Office for the Protection of the Constitution, not in parliaments, courts, or the civil service.”

Notably, the International Auschwitz Committee has also called for closer monitoring of the AfD in the Bundestag as a result of the raid.