Catastrophic Repercussions of Tigray Conflict, Would It Lead to Ethiopia’s Split?

.jpg)

Ethiopia has made headlines over the past few years for a number of positive developments in the country, thanks to its rapid economic growth and transition to a democratic political system, following decades in which Ethiopia was among the poorest countries.

Yet, the country is now facing a military confrontation and a humanitarian crisis in the northern province of Tigray. The situation there may have serious repercussions on the future of the country, and this may have serious repercussions even on its neighbors.

The conflict threatens to destabilize Africa’s second most populous country, where thousands of people have already been killed.

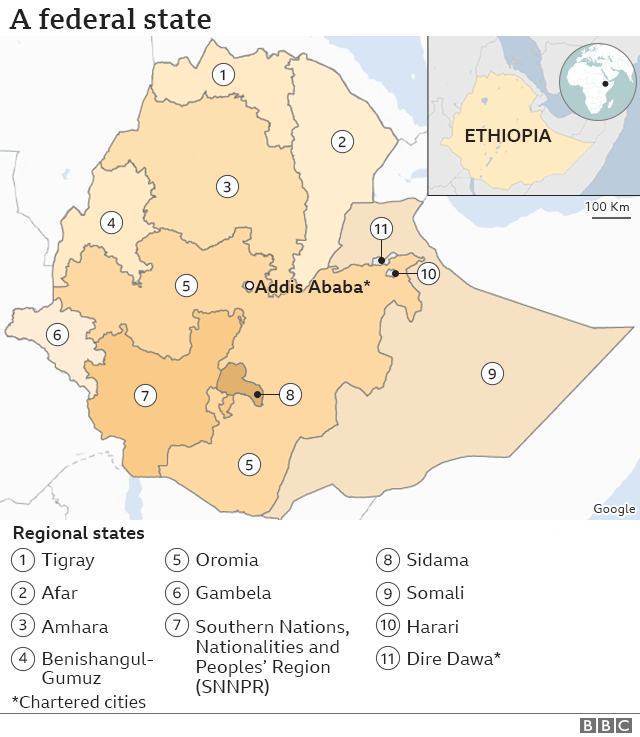

The nine-month-long war between Tigrayan rebel forces and the Ethiopian army and its allies has been mostly contained in the Tigray region, but the fighting is spreading into the neighboring regions of Amhara and Afar.

The Tigrayan forces making significant territorial gains, including capturing the regional capital, Mekelle, in June after Ethiopian troops withdrew and the government declared a unilateral ceasefire

There are increasing concerns about Ethiopian unity as the conflict in the northern Tigray region escalates.

Tigray Crisis

The conflict erupted in Tigray in November 2020 after a falling-out between prime minister, Abiy Ahmed, and the Tigray ruling party that had dominated Ethiopia’s government for nearly three decades.

Ethiopia, Africa’s second-most populous country with about 115 million people, was grappling with daunting economic and social challenges well before a political feud between Mr. Abiy and the Tigray Liberation Front (T.P.L.F) erupted into violence.

Combined with surging ethnic violence in other parts of Ethiopia, including its most populous region, Oromia, the Tigray war has stoked fears of a wider crisis with the potential to tear apart Ethiopia and spread to neighboring countries, destabilizing the entire Horn of Africa.

More than 5 million people, the great majority of Tigray’s population, urgently need assistance, United Nations and local officials say. Fighting has displaced 1.7 million people from their homes, and more than 63,000 have fled to Sudan.

Who are the T.P.L.F. and the Tigrayans?

The T.P.L.F. began in the mid-1970s as a small militia of Tigrayans, a group that was long marginalized by the central government, fighting against Ethiopia’s military dictatorship.

Ethiopia’s two biggest ethnic groups, the Oromo, and the Amhara, make up more than 60 percent of the population, while Tigrayans, the third-largest, are just 6 to 7 percent. Yet the T.P.L.F. became the most powerful rebel force in the country, eventually leading an alliance that toppled the government in 1991.

The rebel alliance became Ethiopia’s ruling coalition, with the T.P.L.F. at its head.

Meles Zenawi, who headed the T.P.L.F., led Ethiopia from 1991 until his death in 2012, a period in which Ethiopia emerged as a stable country in a turbulent region and enjoyed significant economic growth. But the government systematically repressed political opponents and curtailed free speech, and torture was commonplace in government detention centers.

Anti-government protests that erupted in 2016 paved the way for Mr. Abiy, whose father is Oromo, to become prime minister in 2018. His government purged Tigrayan officials and charged some with corruption or human rights abuses, incensing the Tigrayan leadership.

In 2019, Mr. Abiy consolidated his power by creating a new party that was effectively the former governing coalition minus the Tigrayans, who refused to join.

But the T.P.L.F. still controlled the Tigray regional government and an array of security forces that were estimated to number as many as 250,000 armed men, the International Crisis Group said at the start of the war.

In the war, the government has set out to capture or kill T.P.L.F. figures who include some of Ethiopia’s former political and military leaders. In January, the federal government stripped the T.P.L.F. of its status as a legal party and in May it labeled the group as a terrorist organization.

Rebellious’ Demands

The Tigrayan forces have said they will not stop fighting until PM Abiy submits to a number of conditions. This includes the end of the federal government's blockade of Tigray and the withdrawal of all opposing troops - the Ethiopian army, forces from other Ethiopian regions and the Eritreans fighting alongside them.

The blockade refers to the federal government's shutdown of all electrical, financial and telecommunications services in Tigray since the Mekelle withdrawal in June. International organizations have also had difficulty getting much-needed aid through.

The General Tsadkan Gebretensae stated that Tigrayan forces will continue to fight - including in Afar and Amhara regions - until their ceasefire conditions have been met.

"All our military activities at this time are governed by two major objectives. One is to break up the blockade. The second is to force the government to accept our terms for a ceasefire and then look for political solutions."

The general added that the Tigrayans are not aiming to dominate Ethiopia politically as they have in the past. Instead, they want Tigrayans to vote in a referendum for self-governance.

Militia Involvement

The Ethiopian arena has recently witnessed the mobilization of special forces and militias from a number of regions to the Tigray region to support the military operations carried out by government forces. This has raised many concerns about the widening of the conflict in the troubled region and pushing the country into the abyss of a complete civil war.

Regular forces from the Amira region bordering southern Tigray have been fighting alongside government forces since Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed began military operations in Tigray last November.

But now regular and irregular forces from six other regions are joining the ranks of the government forces, although they were not previously involved in the conflict in Tigray.

It is noteworthy that the system of government in Ethiopia is of a federal nature, as the country is divided into ten regional states on the basis of ethnicity, which are largely self-governing, while each region has special forces in addition to local militias composed mostly of farmers, which are very similar to guard units.

In this, Bloomberg Agency quoted Semenhei Ayalu, an official in the Gojam district of Amhara, as saying, "We have sent more than two thousand militia members to the battlefront."

Neighboring Eritrea also sent troops to fight alongside government forces and Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed.

Regional Instability

The crisis in the region has not only affected Ethiopia, but also spread across the country's borders, as thousands of refugees crossed the border into Sudan.

Forces from neighboring Eritrea took part in the attack on TPLF fighters in November. Eritrean support is due to the country's president, Isaias Afwerki, being a "moral enemy" of the Tigray Liberation Front, which ruled Ethiopia when the two countries were at war over a border dispute.

Despite the recent successes of the Tigray Liberation Front, Eritrean forces are still stationed in Tigray but appear to have retreated to the north near the common border.

There is also a risk that the federal government's focus on its military effort in Tigray could weaken its involvement in supporting the government in Somalia against al-Shabab militants.

"The war is really regional," says Horn of Africa analyst Rashid Abdi.

Some experts, such as Abdi, argue that the conflict could weaken the Ethiopian state, which could have devastating regional consequences.

For example, the Tigray crisis could encourage other nationalities in the multi-ethnic country to stand up to the central government as well.

Seeking to calm tensions a day after the fighting began, UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres warned that "Ethiopia's stability is important to the entire Horn of Africa."

The UN Human Rights Council called for the rapid withdrawal of Eritrean forces and an immediate halt to all human rights violations in Tigray.

Famine Disaster & Human Rights Violations

The Tigray region again suffers from a complete cut off of communications, including telephone lines and internet service, since the withdrawal of Ethiopian forces from the region.

The region had been isolated, represented by the interruption of communications with the beginning of the conflict, while the government still imposed strict restrictions on the work of journalists in the region to hide the real catastrophic conditions in the region.

The UN says an estimated 5.2 million people in Tigray need humanitarian assistance, while the recent spread of fighting to Afar region has left thousands there displaced and in desperate need of food and shelter. Food experts say 400,000 people in Tigray are experiencing "catastrophic levels of hunger"

The conflict has caused a massive humanitarian crisis. The United Nations' children's agency, UNICEF, said that more than 100,000 children in Tigray could suffer life-threatening malnutrition in the next year, while half of the pregnant and breastfeeding women screened in the region are acutely malnourished.

All aid routes into Tigray are blocked except for one road from Afar region where food convoys have recently been attacked, reportedly by pro-government militias.

The Tigrayan forces say they are hoping to force open a new aid corridor via Sudan by defeating the Ethiopian army and Amhara troops stationed there

The involvement of new Ethiopian local militias in the conflict raised many concerns about the region's vulnerability to the famine disaster and further human rights violations and even out of control.

For his part, Yohannes Woldemariam, an independent Ethiopian analyst based in the United States, warns of the repercussions of the involvement of new local militias in the conflict.

"The situation is developing very dangerously, as there are many groups fighting, but it must be noted that the issues and agendas of these groups differ," he added.

Abiy Ahmed's last comments fueled these fears, as he used words such as "drugs", "cancer" and "disease" to refer to the Tigray Liberation Front. Commenting on this escalation of words, Chitel Tronoval the Professor of Peace and Conflict Studies at Björknes College in Norway said that this language "represents a very dangerous discourse that may lead to genocide."